DIpil Das

Introduction

What’s the Story? Global production of electronic goods such as automobiles, appliances and consumer electronics products (PCs, smartphones and gaming consoles) continue to be plagued by shortages of semiconductor chips. In this report, we discuss the root causes of the global chip shortage and its implications for retailers, with a focus on the US. We also offer an outlook for the shortage. The appendix of this report provides a brief overview of the global chip industry. Why It Matters Although there are many headlines decrying “the chip shortage,” there are in fact many chip shortages, due to the wide variation in materials and technologies used in the manufacture of different types of chip. The chip shortage affects retailers in terms of obtaining products for sale, equipment for use in stores and vehicles with which to transport products. Due to the billions of dollars and multiyear horizons needed to build a new chip factory, there is no instantaneous solution at hand, though prior capacity increases continue to advance and new, aggressive capacity increases have been announced and launched.The Global Chip Shortage: Coresight Research Analysis

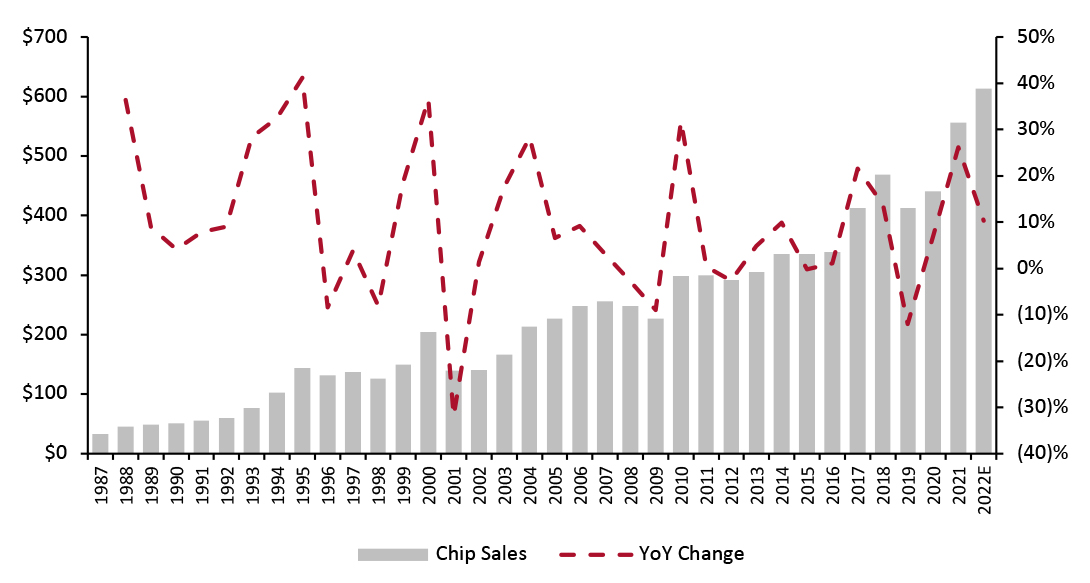

Root Causes The increasing use of electronics for automobiles and appliances as well as consumer demand for smartphones, large-screen TVs, smartwatches and gaming consoles are drivers of global chip demand. Chipmakers had already begun capacity-addition plans when three factors came into play that put even more pressure on an already tight capacity situation: trade disputes (including the blocking of Chinese telecom equipment makers), pandemic-led shifts in demand for office and entertainment products, and heavy volatility in automobile purchases. Further magnifying the problem, new capacity additions are generally for advanced, denser chips, whereas there is still healthy demand for older-technology chips, whose capacity is more limited. Below, we explore each of these contributing causes of the global chip shortage. Dependence on Chips Is Increasing Consumers continue to enjoy ever-increasing convenience and usefulness from electronic devices such as PCs, smartphones, wearables, gaming consoles and electrified automobiles, which has fueled healthy increases in demand for chips. The global chip industry is highly cyclical, featuring periods of boom and bust due to overcapacity and undercapacity, as shown in Figure 1. During the period 1987‒2020, global semiconductor sales grew at a 7.9% CAGR, compared to a 2.8% CAGR for global GDP during the same period (based on data from the World Bank.)Figure 1. Global Semiconductor Industry Sales (Left Axis; USD Bil.) and YoY Growth (Right Axis; %) [caption id="attachment_151196" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: SIA/WSTS/Coresight Research[/caption]

Political Disputes Lead to Inventory Builds

In May 2019, then US President Trump signed an executive order banning Chinese telecommunications equipment makers Huawei and ZTE on national security grounds, which were issued as final orders by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). In November 2021, current US President Biden signed a law banning the two companies from receiving licenses from the FCC.

Huawei is the world’s largest telecom equipment manufacturer, with revenues of $99.9 billion and a 35.3% share of the global telecom services market in 2021, according to Statista. ZTE holds a 7.0% share.

Huawei therefore accumulated supplies of key chips, which amounted to a two-year supply, according to an article in Nikkei Asia in May 2020, but this chip accumulation likely created massive supply-demand imbalances for these chips due to the company’s large size.

The Pandemic Shifted Consumer Demand to Products for Working and Relaxing at Home

The Covid-19 pandemic created bottlenecks and delays in global supply chains—and the global semiconductor industry is highly complex and largely concentrated in multiple countries in Asia. The absence of any one material or step in chip manufacturing can mean that devices cannot be completed, and the waves of lockdowns and port closures during the pandemic inhibited global supply chains.

Moreover, the widespread shift to working from home increased demand for PCs and peripherals such as webcams for work; for large-screen TVs and gaming consoles for enjoying entertainment; and for appliances to make longer stays at home more comfortable—creating kinks in a previously more predictable supply chain.

Not All Chips Are Created Equal

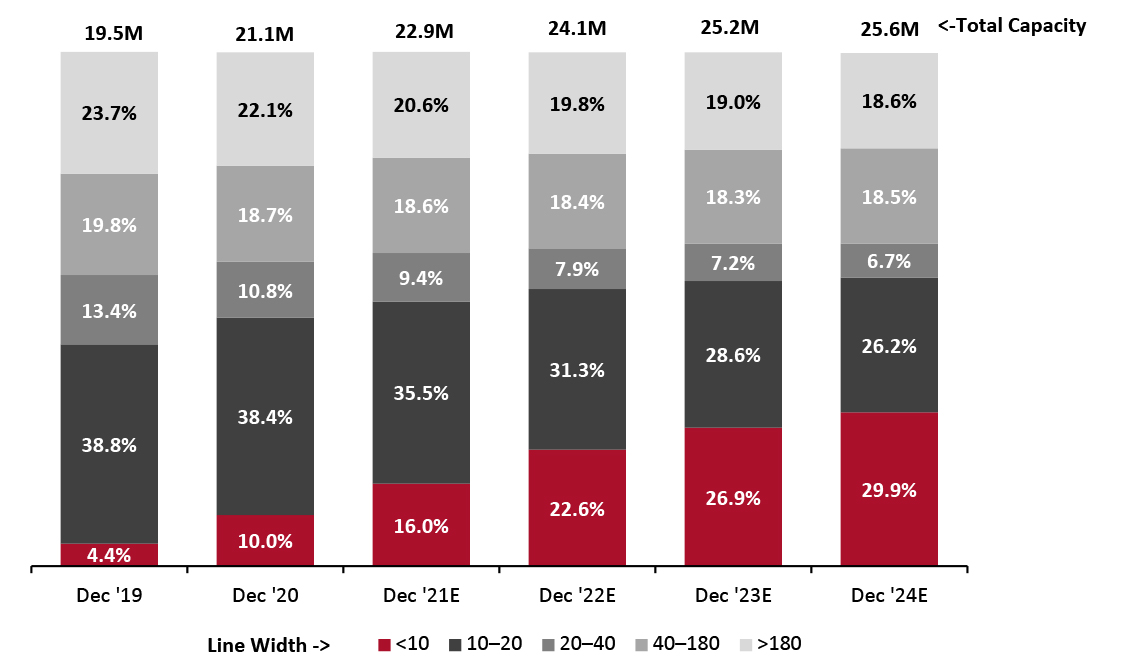

Many commonly used essential chips, such as microcontrollers or voltage regulators, use older-generation technology, whereas chipmakers have greater financial incentives to add leading-edge technologies.

Most digital chips are made from silicon wafers, but analog chips use other materials such as gallium arsenide. Chips of different technologies are attached to substrates together to form modules called systems-on-a-chip.

Moreover, chip technology has improved over time, with chipmakers able to reduce the size of features and lines on the chip surface. This is known as Moore’s Law: Intel Co-Founder Gordon Moore observed that the number of chips produced on a wafer doubled every two years—i.e., they became smaller. With the cost of processing a silicon wafer staying flat, silicon economics enable chipmakers to generate more revenue from a wafer with newer technologies.

TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) possesses the current state-of-the-art technology, offering 5nm (five nanometers—five billionths of a meter) line widths currently and with plans to offer chips with 3nm in the second half of 2022.

Figure 2 shows that smaller chips with narrower geometry will take an increasing share of total chip capacity through 2024, while the share for still-needed less-dense chips is set to decline slowly.

Source: SIA/WSTS/Coresight Research[/caption]

Political Disputes Lead to Inventory Builds

In May 2019, then US President Trump signed an executive order banning Chinese telecommunications equipment makers Huawei and ZTE on national security grounds, which were issued as final orders by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). In November 2021, current US President Biden signed a law banning the two companies from receiving licenses from the FCC.

Huawei is the world’s largest telecom equipment manufacturer, with revenues of $99.9 billion and a 35.3% share of the global telecom services market in 2021, according to Statista. ZTE holds a 7.0% share.

Huawei therefore accumulated supplies of key chips, which amounted to a two-year supply, according to an article in Nikkei Asia in May 2020, but this chip accumulation likely created massive supply-demand imbalances for these chips due to the company’s large size.

The Pandemic Shifted Consumer Demand to Products for Working and Relaxing at Home

The Covid-19 pandemic created bottlenecks and delays in global supply chains—and the global semiconductor industry is highly complex and largely concentrated in multiple countries in Asia. The absence of any one material or step in chip manufacturing can mean that devices cannot be completed, and the waves of lockdowns and port closures during the pandemic inhibited global supply chains.

Moreover, the widespread shift to working from home increased demand for PCs and peripherals such as webcams for work; for large-screen TVs and gaming consoles for enjoying entertainment; and for appliances to make longer stays at home more comfortable—creating kinks in a previously more predictable supply chain.

Not All Chips Are Created Equal

Many commonly used essential chips, such as microcontrollers or voltage regulators, use older-generation technology, whereas chipmakers have greater financial incentives to add leading-edge technologies.

Most digital chips are made from silicon wafers, but analog chips use other materials such as gallium arsenide. Chips of different technologies are attached to substrates together to form modules called systems-on-a-chip.

Moreover, chip technology has improved over time, with chipmakers able to reduce the size of features and lines on the chip surface. This is known as Moore’s Law: Intel Co-Founder Gordon Moore observed that the number of chips produced on a wafer doubled every two years—i.e., they became smaller. With the cost of processing a silicon wafer staying flat, silicon economics enable chipmakers to generate more revenue from a wafer with newer technologies.

TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) possesses the current state-of-the-art technology, offering 5nm (five nanometers—five billionths of a meter) line widths currently and with plans to offer chips with 3nm in the second half of 2022.

Figure 2 shows that smaller chips with narrower geometry will take an increasing share of total chip capacity through 2024, while the share for still-needed less-dense chips is set to decline slowly.

Figure 2. Shares of Monthly Installed Capacity by Geometry (200mm Wafer Equivalents; %) [caption id="attachment_151197" align="aligncenter" width="699"]

Source: IC Insights[/caption]

Order Cancelations Hobble the Automotive Industry

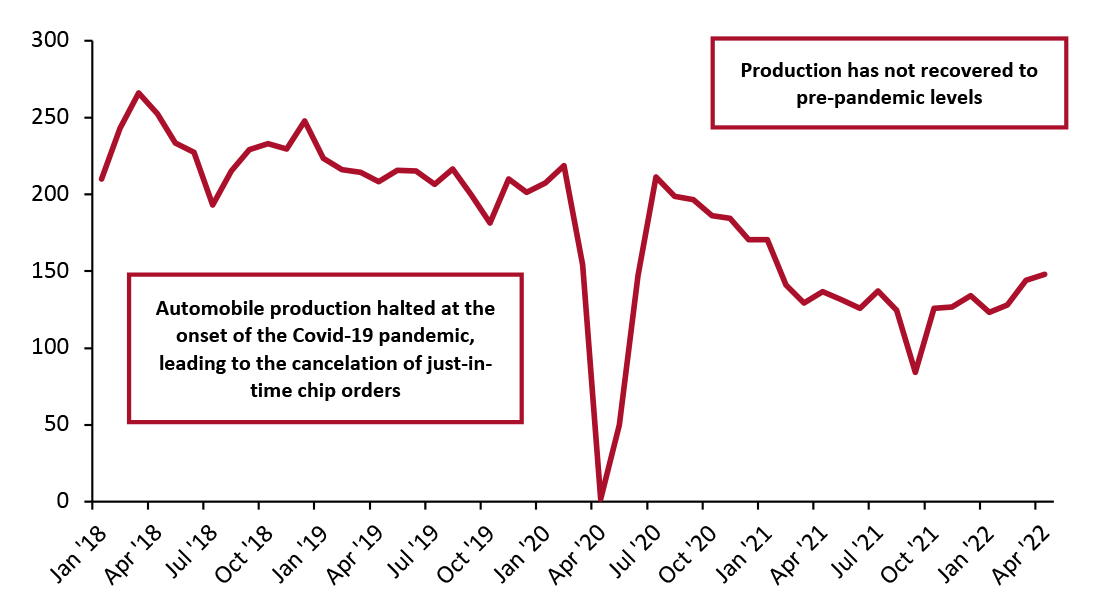

Global automakers slashed production plans at the outset of the pandemic, which led to the cancelation of just-in-time chip orders. The drop in production is shown in Figure 3.

Unfortunately, the factory capacity that had previously been reserved for global automakers was quickly reassigned to other customers. When demand picked up again in late 2020, the carmakers were at the end of the line for new capacity, leading many of them to stop production on certain models or leave out nonessential features due to the unavailability of key chips.

Source: IC Insights[/caption]

Order Cancelations Hobble the Automotive Industry

Global automakers slashed production plans at the outset of the pandemic, which led to the cancelation of just-in-time chip orders. The drop in production is shown in Figure 3.

Unfortunately, the factory capacity that had previously been reserved for global automakers was quickly reassigned to other customers. When demand picked up again in late 2020, the carmakers were at the end of the line for new capacity, leading many of them to stop production on certain models or leave out nonessential features due to the unavailability of key chips.

Figure 3. US Automobile Production (Thous. Units) [caption id="attachment_151198" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve[/caption]

Implications for Retailers

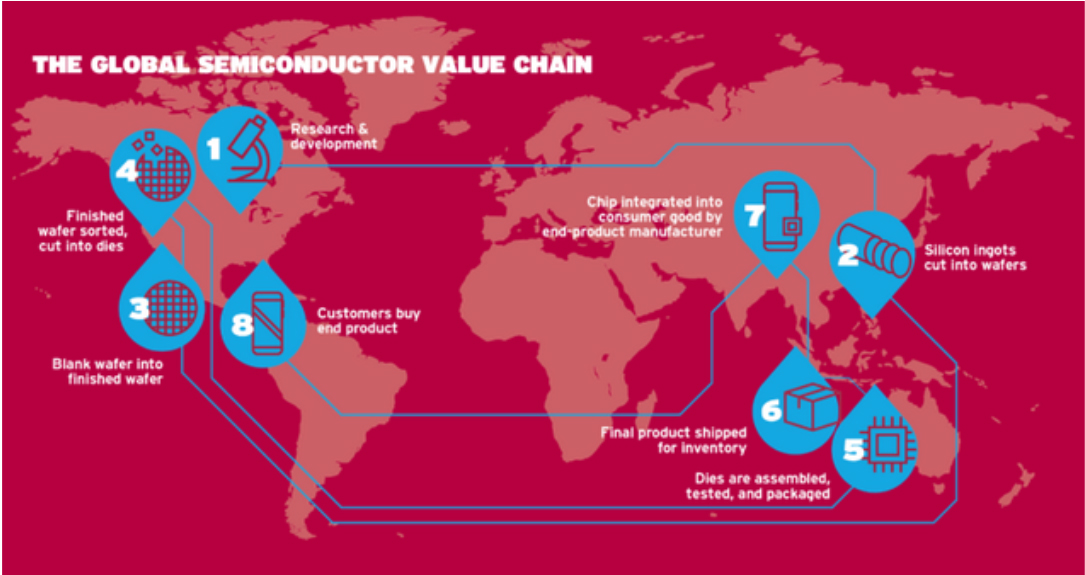

Whereas many of the largest chip designers are US companies, much of the global manufacturing, assembly and test, and electronics manufacturing ecosystem is concentrated in Asia, as illustrated in the image below, which depicts the globe-spanning journey from raw materials to processed wafers to chips to final products.

[caption id="attachment_151199" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve[/caption]

Implications for Retailers

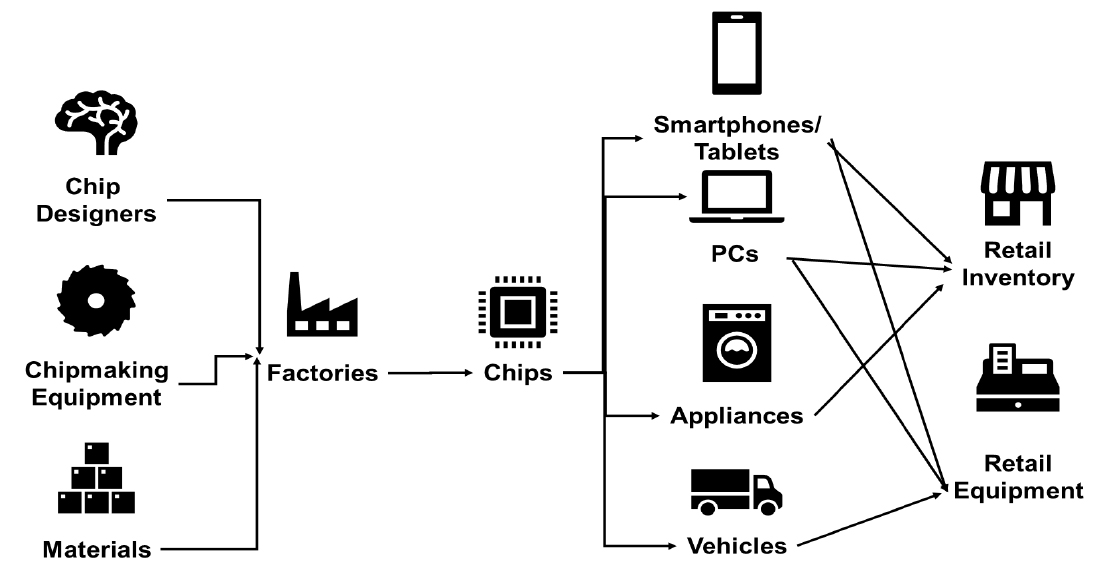

Whereas many of the largest chip designers are US companies, much of the global manufacturing, assembly and test, and electronics manufacturing ecosystem is concentrated in Asia, as illustrated in the image below, which depicts the globe-spanning journey from raw materials to processed wafers to chips to final products.

[caption id="attachment_151199" align="aligncenter" width="700"] The global semiconductor value chain

The global semiconductor value chain Source: semiconductors.org [/caption] Retailers are exposed to the global semiconductor supply chain, both as vendors of electronic equipment and as users of electronic equipment. We identify three key ways in which retailers are impacted by the global chip shortage:

- Product availability—During the 2021 holiday season, retailers reported longer lead times and the unavailability of PCs, smartphones and gaming consoles, as supply was limited due to a lack of chip availability.

- Equipment availability—The chip shortage affects the availability of in-store hardware such as PCs (including point-of-sale (POS) terminals), cameras, edge computers and even RFID (radio-frequency identification) chips.

- Vehicle availability—The steady increase in e-commerce means higher demand by retailers and logistics providers for vehicles, whose production was hobbled by the global chip shortage. Vehicle manufacturers completely stopped production of some lines completely, with many models held up due to the availability of key parts, and in other cases, shipped vehicles without certain features. Electric-powered vehicles depend even more on key parts.

Figure 4. The Chip Supply Chain as It Relates to Retail [caption id="attachment_151200" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

Outlook: Help Is on the Way… Gradually

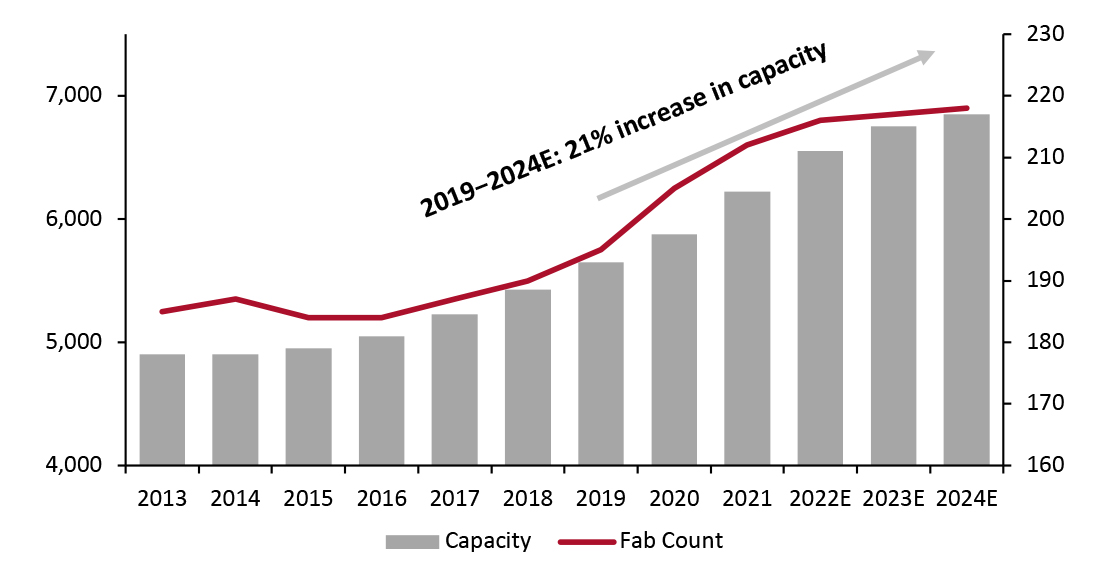

Prior to the pandemic, the global semiconductor industry was already in the midst of a capacity-expansion phase to accommodate expected increases in demand due to the increasing electrification of automobiles, the growing usage of smartphones and the move to cloud computing—and plans have been boosted to address the current chip shortage.

Figure 5 illustrates a forecast of expected chip capacity and the number of semiconductor factories (known as “fabs”). In the figure, capacity is reflected in the equivalent number of 200mm-diameter wafers (i.e., many wafers produced today are 300mm in diameter.)

Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

Outlook: Help Is on the Way… Gradually

Prior to the pandemic, the global semiconductor industry was already in the midst of a capacity-expansion phase to accommodate expected increases in demand due to the increasing electrification of automobiles, the growing usage of smartphones and the move to cloud computing—and plans have been boosted to address the current chip shortage.

Figure 5 illustrates a forecast of expected chip capacity and the number of semiconductor factories (known as “fabs”). In the figure, capacity is reflected in the equivalent number of 200mm-diameter wafers (i.e., many wafers produced today are 300mm in diameter.)

Figure 5. Semiconductor Capacity (Left Axis; 200mm Equivalents) and Fab Count (Right Axis) [caption id="attachment_151201" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: SEMI.org[/caption]

Building a new leading-edge chip factory costs billions of dollars and takes several years to complete, so capacity cannot be added overnight. Still, chipmakers are able to run factories at above-ideal capacity levels, though this brings added cost due to the additional wear and tear on equipment.

Chipmakers have responded to shortages by increasing their capacity-addition plans. Moreover, vertically integrated manufacturers such as Intel have announced programs to manufacture chips for other parties, and governments have entered the fray to increase domestic chipmaking capacity. Examples include the following:

Source: SEMI.org[/caption]

Building a new leading-edge chip factory costs billions of dollars and takes several years to complete, so capacity cannot be added overnight. Still, chipmakers are able to run factories at above-ideal capacity levels, though this brings added cost due to the additional wear and tear on equipment.

Chipmakers have responded to shortages by increasing their capacity-addition plans. Moreover, vertically integrated manufacturers such as Intel have announced programs to manufacture chips for other parties, and governments have entered the fray to increase domestic chipmaking capacity. Examples include the following:

- In its most recent earnings release (for the fourth quarter of fiscal 2021), TSMC announced a capital spending budget of US$40‒44 billion for 2022, up 33%‒47% from $30 billion in 2021—covering expansion in Taiwan as well as at its existing facility in Arizona.

- In March 2021, Intel announced a strategy called “IDM 2.0,” (IDM stands for “integrated device manufacturing”), which includes a $20 billion investment to build new factories in Arizona in addition to Intel Foundry Services, which will manufacture chips for other companies. In January 2022, Intel announced a new $20 billion investment in a new factory to be located in Columbus, Ohio.

- The proposed US CHIPS for America Act seeks $52 billion in funding to catalyze private-sector investment and help restore US leadership in chip manufacturing, which has been ceded to Asian companies.

What We Think

The chip shortage is not going to disappear overnight, given the inelasticity of capacity due to the years and billions of dollars needed to construct a new, leading-edge chip factory. Still, help is on the way with optimization of existing capacity and the expansion and addition of new capacity. At the same time, consumers and businesses continue to increase their use of chips in consumer and business products and equipment. The best measure that retailers can take is to plan their needs and place orders for product and equipment in advance, while trying to be as flexible as possible. The challenging economic times that are ahead for many economies could cool off an overheated chip market, which would help those who still need chips to access them. There are some signs that demand could be cooling in consumer sectors. At a conference in June, Intel reported that data for the second half had gotten “noisier.” In its second-quarter earnings report, memory and storage vendor Micron reported that industry demand had weakened. These signals of softer demand relieve some of the pressure on the global chip market. Implications for Brands/Retailers- Brands and retailers should place product orders early in order to ensure the receipt of sufficient quantities, particularly as we approach the holiday season.

- The chip shortage can also affect the availability of vehicles, since they are major chip users.

- The chip shortage has implications for the availability of in-store and other hardware, such as PCs, cameras and RFID tags.

- Hardware manufacturers are well-acquainted with the cyclical nature of the chip industry.

- Manufacturers typically sign up a second source for key components.

- Older-generation, commodity chips are often those in shortage due to chipmakers’ incentives to add capacity for make leading-edge chips.

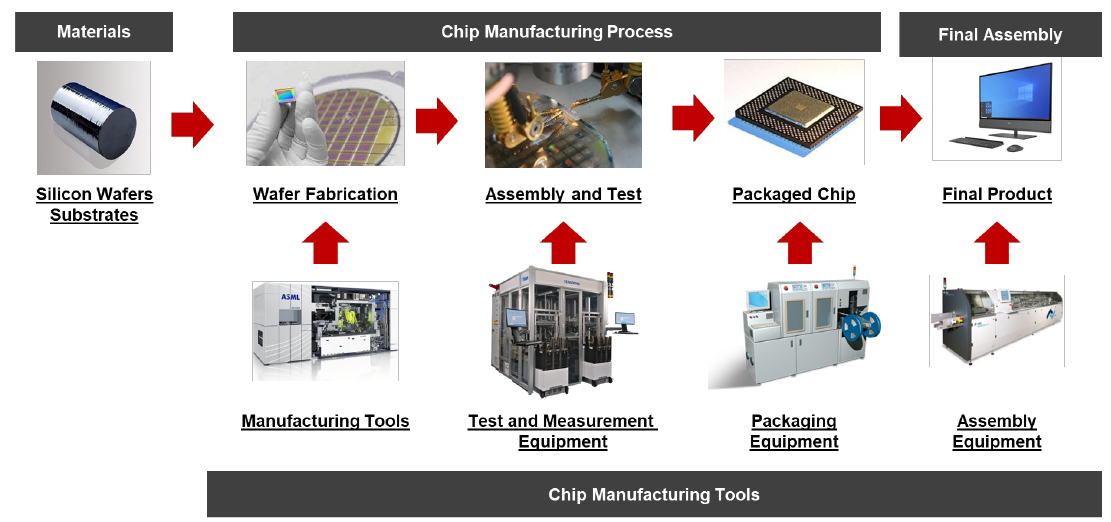

Appendix: Overview of the Global Chip Industry

The semiconductor industry includes myriad chip designers, materials suppliers, equipment makers and manufacturers. A chip starts out as a wafer made of silicon or other material, which is processed, enclosed in a hermetically sealed package with electrical connections and tested throughout the process. At a high level, the key players in the global chip industry include the following:- Chip design companies—Apple, Nvidia, Qualcomm

- Materials vendors such as Shin-Etsu

- Vertically integrated chip designers/manufacturers—Intel, Samsung

- Chip manufacturers/foundries—Intel, Samsung, TSMC

- Chip manufacturing equipment makers—Applied Materials, ASML, Lam Research

- Assembly and test services and equipment such as ASE Technology and Keysight Technologies (formerly Agilent/Hewlett-Packard)

- Electronic device makers—Apple, HP, Electrolux, Lenovo, Microsoft, Samsung, Sony, Whirlpool, in addition to major global automobile manufacturers

Appendix Figure 1. Stages in Chip Manufacturing [caption id="attachment_151202" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

“Fabless” Is Fabulous

The global chip industry has bifurcated as chipmakers elect to be “fabless” (i.e., not owning their own chip factories) or vertically integrated, on the model of Intel and Samsung. The attraction of the fabless model is the enormous investment and operating cost of chip factories, which is particularly onerous when utilization falls in a downturn. A new category of pure manufacturers (called foundries) such TSMC has emerged, whose only business is manufacturing chips for fabless customers. While Intel is a design and manufacturing powerhouse that long led the industry, TSMC has surpassed Intel in terms of smaller line widths—although Intel has resolved to regain its manufacturing leadership and leads in many other aspects of chip design and manufacturing.

Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

“Fabless” Is Fabulous

The global chip industry has bifurcated as chipmakers elect to be “fabless” (i.e., not owning their own chip factories) or vertically integrated, on the model of Intel and Samsung. The attraction of the fabless model is the enormous investment and operating cost of chip factories, which is particularly onerous when utilization falls in a downturn. A new category of pure manufacturers (called foundries) such TSMC has emerged, whose only business is manufacturing chips for fabless customers. While Intel is a design and manufacturing powerhouse that long led the industry, TSMC has surpassed Intel in terms of smaller line widths—although Intel has resolved to regain its manufacturing leadership and leads in many other aspects of chip design and manufacturing.