Nitheesh NH

Introduction

Just as in other markets, department stores in the UK are facing a period of turbulence. Department stores are being hit by higher costs and long leases even as spending moves online, while often simultaneously struggling with huge debt piles. Two of the UK’s biggest names—Debenhams and House of Fraser—have entered administration (bankruptcy). Meanwhile, M&S is closing stores and John Lewis, which has long been an outperformer in the sector, is slashing costs amid deepening losses. We include timelines for House of Fraser, Debenhams and M&S in an appendix.High-Profile Chains Are Faltering

A host of high-profile apparel and department store chains entered into administration or used company voluntary arrangements (CVAs) to prevent business collapse in 2018 and 2019. Examples include Arcadia Group, Debenhams, House of Fraser, Jack Wills, Karen Millen, L.K. Bennett, New Look Group, Pretty Green and Select. Some of these chains have been taken over by new operators and are still in business but have closed (or have plans to close in 2020) some outlets. Apparel and department store retailers have shown signs of financial strain in recent times, with some issuing a succession of profit warnings before entering into insolvency processes. L.K. Bennett reported an operating loss of £5.9 million excluding exceptional costs in fiscal year 2017, compared to an operating profit of £0.1 million the year before. New Look Group’s UK division incurred an underlying operating loss of £54.8 millon in fiscal year 2018 as compared to an operating profit of £97.3 million in fiscal year 2017. Among the department stores, Debenhams issued three profit warnings in fiscal year 2018 due to a continuous slump in its UK sales. House of Fraser urgently sought new funds to pay its quarterly store rent bills and purchase new stock for the Christmas 2018 trading period. These financial difficulties compelled both companies to initiate administration procedures and rationalize their store portfolios.Where Did Department Stores Go Wrong?

Midmarket generalist retailers with substantial store networks—such as Debenhams and M&S—continue to be challenged by structural shifts in supply and demand: Supply: Enjoying greater choice in terms of where and how they shop, consumers are splintering away from midmarket generalists to more specialized, price-focused or digital-first retailers—from expanding discount options such as Primark to online-only rivals, not least Amazon. Meanwhile, brand-heavy retailers such as House of Fraser are seeing shoppers switch to price-competitive digital rivals, including Amazon and Zalando. The issue is no longer simply one of overcapacity in retail—the notion of “capacity” is meaningless in a digital age that is characterized by a multitude of online retailers as well as marketplaces, drop-shipping models, direct-to-consumer brands and rental or subscription options. Demand: At the same time, we think that shoppers are increasingly attracted to niche brands and products that resonate with consumers’ identities, lifestyles or preferences, and thus provide a clear emotional connection. Non-homogeneous societies and consumer identities do not fit well with midmarket generalist retailers. UK department stores have gradually been losing their customers to a host of competitors, including value-led retailers, brands selling direct to consumers and online pure-plays. Eventually, without a compelling proposition, those in the middle ground struggled with their positioning, with the resulting sales declines deleveraging their substantial store-based costs. Adjacent to this was the overspacing of the sector. Department store chains acquired large amounts of retail space during previous boom times, when e-commerce was much less significant and competition more subdued. These chains then failed to shed space quickly or radically enough, often because they had signed long leases, with some stores tied in for as long as 40 years. For some retailers, the deleveraging of costs increased the debt burden, leaving them with even less funding to re-invest in renewing their relevance.What Has Been Tried but Failed?

Major department store chains tried—and in some cases, are still trying—to implement a number of strategies to support shopper numbers and stabilize the top line. However, we note that most of these have failed to move the dial in terms of reviving sales. E-Commerce and Digital. For a number of years, major retailers (including department stores) poured investments into e-commerce with the apparent belief that this would drive sales growth. Instead, e-commerce became simply table stakes in retail, while retailers failed to fix the fundamental issues with their propositions; they fixed the supply without strengthening demand. Although most department stores have recognized the need to invest in digital capabilities, chains have historically been well behind the curve. House of Fraser made some sound investments in digital efforts, launching its first e-commerce site in 2007. However, the company did not begin a major and much-needed upgrade to its website until April 2017, even though the retailer’s online sales constituted 20% of total sales by that point. At M&S, former CEO Marc Bolland unveiled a strategy in November 2010 to make the company a leading UK multichannel retailer by 2013 and a leading international multichannel retailer by 2015. In 2013, the company opened its Castle Donington distribution center, which was designed to support the online expansion of M&S. In 2014, the retailer overhauled its website, bringing the platform in house and incorporating a major push on online editorial content. Even with these efforts, M&S’s total UK general merchandise sales have continued to dwindle. Moreover, despite investments of hundreds of millions of pounds under Bolland, management claimed in May 2018 that the company’s online capability is well behind the best of its competitors and its website is “too slow.” The Castle Donington fulfilment center has also struggled to cope with peak demand. At Debenhams, digital was one component of the company’s final strategy prior to administration—it announced plans in April 2017 to be digital-driven, with “mobile unifying channels and interaction with customers.” Debenhams upgraded its mobile site in the second half of fiscal year 2017. Experience. In April 2017, Debenhams embraced experiential retailing to make store visits more fun and less functional. As part of its final strategy before it entered administration, the company aimed to project itself as a destination for “social shopping,” with new services, experiences and products focusing around three key areas: beauty and beauty services; fashion via accessories; and food and events, which was termed “Meet Me @ Debenhams.” With a substantial and somewhat-dated store estate, however, evidence of experiential retail was often thin on the ground, and the strategy failed to sufficiently drive traffic and sales. Department stores, particularly those with a premium positioning, must provide quality shopping experiences. However, we are skeptical that a focus on experiential retail is an effective strategy for those department stores at the very middle of the market, which are treading a fine line between value and premium. We do not believe that such midmarket chains can win back meaningful shopper volumes through a relatively modest increase in services such as food and beverages or beauty—especially if there remains underinvestment in core estates. [caption id="attachment_99287" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

Private Label. Retailers frequently point to the exclusiveness offered by private-label products as a potential savior of chains such as department stores. We think the evidence is less positive.

For a number of years in the 2000s, Debenhams migrated its clothing to a largely private-label offering, eschewing major brands in favor of its own, including those in the Designer at Debenhams collection. This boosted margins and meant that shoppers couldn’t compare products (and so prices) directly versus competitors, including online. However, the company ultimately failed to keep its Designers at Debenhams brands fresh, with most of the current contributors having been part of the range for many years.

In the early to mid-2010s, House of Fraser made a major push into private-label apparel, with names such as Biba and Label Lab. The company maintained a large number of major third-party brands, but we think the heavy push into private label did not offer a good fit with the company’s more premium positioning and younger customer base. That said, House of Fraser retreated from this strategy in 2016 and again in 2018 by axing a number of private labels.

Finally, M&S is a 100% private-label retailer in apparel, and this has not prevented it seeing declines in this category.

Shutting stores. One of the most recent actions—common across Debenhams, House of Fraser and M&S—is the closure of stores. Unlike the factors discussed above, this is about cutting costs rather than boosting sales. We discuss store closures, and the events that prompted them, in the following sections.

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Private Label. Retailers frequently point to the exclusiveness offered by private-label products as a potential savior of chains such as department stores. We think the evidence is less positive.

For a number of years in the 2000s, Debenhams migrated its clothing to a largely private-label offering, eschewing major brands in favor of its own, including those in the Designer at Debenhams collection. This boosted margins and meant that shoppers couldn’t compare products (and so prices) directly versus competitors, including online. However, the company ultimately failed to keep its Designers at Debenhams brands fresh, with most of the current contributors having been part of the range for many years.

In the early to mid-2010s, House of Fraser made a major push into private-label apparel, with names such as Biba and Label Lab. The company maintained a large number of major third-party brands, but we think the heavy push into private label did not offer a good fit with the company’s more premium positioning and younger customer base. That said, House of Fraser retreated from this strategy in 2016 and again in 2018 by axing a number of private labels.

Finally, M&S is a 100% private-label retailer in apparel, and this has not prevented it seeing declines in this category.

Shutting stores. One of the most recent actions—common across Debenhams, House of Fraser and M&S—is the closure of stores. Unlike the factors discussed above, this is about cutting costs rather than boosting sales. We discuss store closures, and the events that prompted them, in the following sections.

House of Fraser, Debenhams, M&S and John Lewis

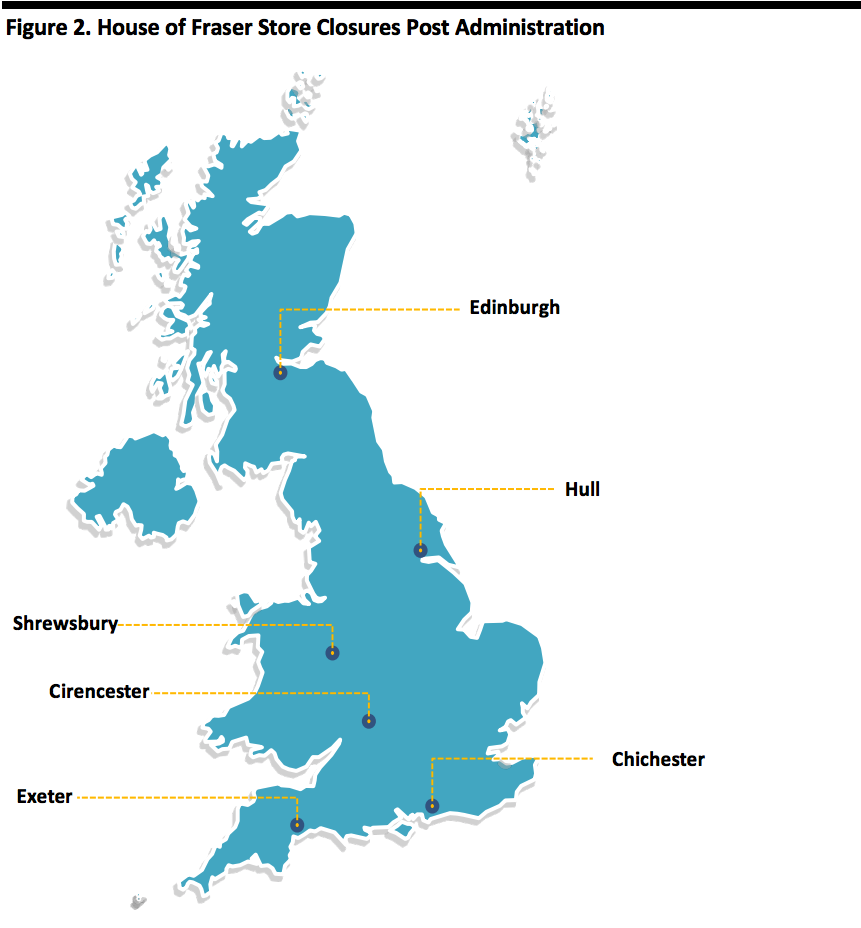

We outline the challenges four of the big department store chains have faced and review the strategies they have outlined in response. House of Fraser’s Administration House of Fraser has traditionally been pitched as much more upmarket than Debenhams or M&S, with a brand-heavy offering. This premium positioning seemed to give the company greater resilience until relatively recently. House of Fraser had been outperforming its industry peers even as market conditions grew challenging: In 2015 and 2016, House of Fraser continued to report solid comparable sales growth. Its troubles therefore appear to have emerged far more recently than those at Debenhams or M&S. Where Did House of Fraser Go Wrong? House of Fraser's collapse can be attributed, at least in part, to its former owners’ management of the company and their apparent unwillingness to invest in the business. House of Fraser was bought by Chinese retailer Nanjing Cenbest, a subsidiary of The Sanpower Group, for £480 million in 2014. Under Sanpower, the company saw a raft of management changes. The then Executive Chairman Don McCarthy left almost immediately after the company’s acquisition, and CEO John King, who initiated the takeover deal, left in early 2015. House of Fraser appointed Nigel Oddy as CEO; he resigned in 2016 after less than two years in the role. The company replaced Oddy with Alex Williamson, former CEO of Goodwood Racecourse, who had a nonretail background. Williamson started the role in July 2017, which left the company without a CEO for over six months, including through the crucial 2017 Christmas trading period. 2016 and 2017 saw a clearing out of much of House of Fraser’s existing senior management, and a number of those roles were filled by people from nonretail backgrounds. In April 2018, another Chinese retailer, C.banner International, signed a memorandum of understanding with Nanjing for the potential acquisition of a 51% stake in House of Fraser and to inject a much-needed £70 million into modernization and restructuring. The following month, House of Fraser reported a 2017 loss of £43.9 million and an accumulated debt of £390 million. Subsequently, in June 2018, the company . The owners said that the unprofitable stores had created an unsustainable cost base, which without restructuring may lead to the collapse of the business. The CVA was approved by the creditors in the same month, enabling the company to go ahead with the proposed store closures. However, C.banner pulled out of the deal and dropped the plan to invest in House of Fraser in August, citing a dive in its own share price as the reason for its withdrawal. This forced the department store chain to look to lenders and alternative investors for the required funding to keep the business going. House of Fraser urgently sought £50 million to avoid collapse: £25 million to meet its quarterly rent bill due in September 2018; £10 million to settle a short-term overdraft; and funds to purchase stock for the peak Christmas trading period. Administration and After In August 2018, House of Fraser entered administration and was acquired by UK-based sports retailer Sports Direct for a sum of £90 million. Sports Direct owner Mike Ashley promised to keep as many stores open and preserve as many jobs as possible. Over a period of a few months, Ashley managed to save 26 House of Fraser stores from closing by renegotiating with landlords to reduce rent. However, he could not reach agreements with remaining landlords, leading to the closure of five stores by mid-2019. As of April 2019 (Sports Direct’s year-end), House of Fraser was operating 54 of the original 59 stores, with a total retail space of 4.6 million square feet (428,000 square meters). The company closed an additional store in Hull in August, stating that it had become “unviable” and would not live up to customer expectations. [caption id="attachment_99288" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

Despite this plan, in its annual results statement released in July 2019, Sports Direct admitted that the problems at House of Fraser were “nothing short of terminal in nature” and that more store closures are under way. Sports Direct reported that House of Fraser, on its own, recorded a full-year operating loss of £54.6 million. It stated that the House of Fraser acquisition has threatened the future profitability of the group as a whole and added that the company is continuing to review its portfolio in the long term, with an expectation to reduce the number of House of Fraser stores over the next 12 months.

Debenhams’ Administration

Debenhams has been struggling with formidable challenges, including high rents, falling sales and heavy competition. The company initially outlined plans to close 10 underperforming stores. However, as its finances continued to decline, the company revised this number to 50 in October 2018.

Where Did Debenhams Go Wrong?

Many Debenhams stores were tied up on long leases that were signed in 2003 to 2006 when the company was under private-equity . These long-term agreements held the company back from optimizing its store portfolio and implementing closures. Many of the prime-sited large stores came with high rents and high operating costs that included substantial staffing. The company’s UK occupancy costs (including rent, rates and service charges) accounted for £290 million in 2018.

Administration and After

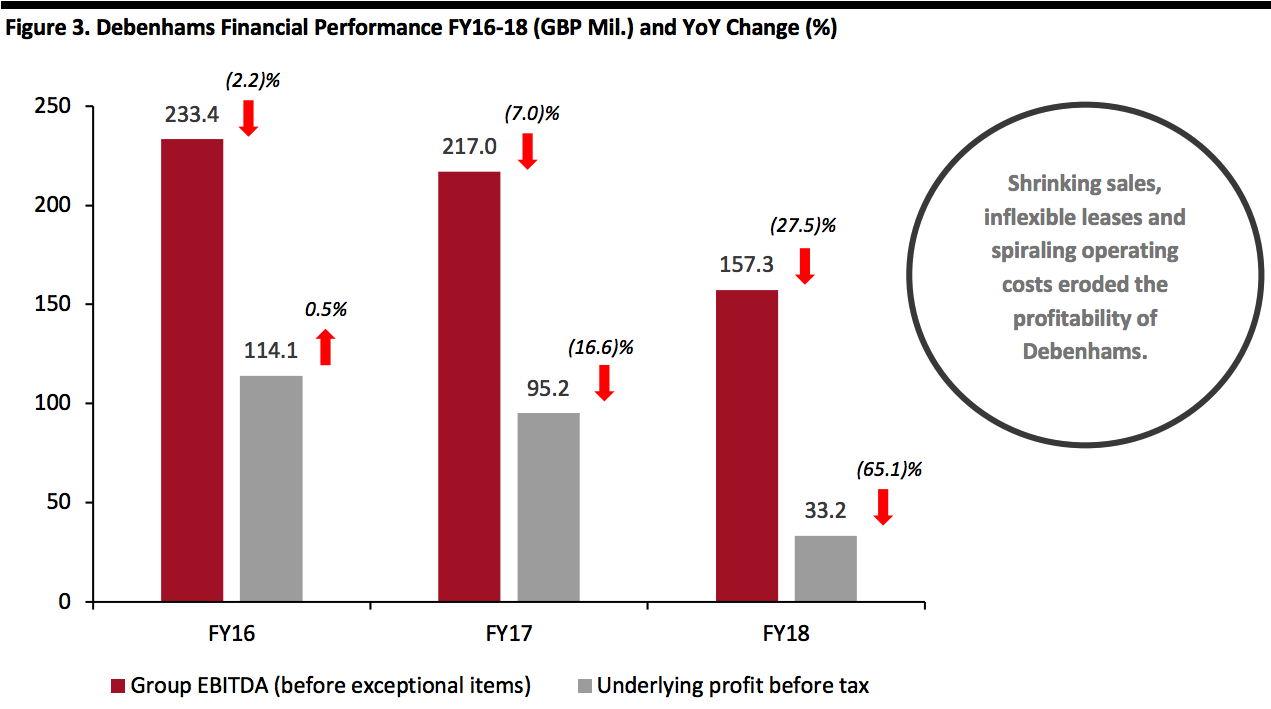

In 2018, Debenhams’ finances deteriorated, and it issued three profit warnings in the year. Another profit warning was then issued in 2019 as sales continued to decline. In its 1H19 results, Debenhams reported statutory revenues of £1,246 million, a 5.5% decline year over year. Group EBITDA, before exceptional items, plunged 36.6% year over year to £65.9 million, and comparable sales were down 5.2% year over year. The company admitted that it would be unable to meet its previous forecasts for the current financial year due to a 6% slide in its UK sales and an increase in costs.

[caption id="attachment_99289" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Coresight Research[/caption]

Despite this plan, in its annual results statement released in July 2019, Sports Direct admitted that the problems at House of Fraser were “nothing short of terminal in nature” and that more store closures are under way. Sports Direct reported that House of Fraser, on its own, recorded a full-year operating loss of £54.6 million. It stated that the House of Fraser acquisition has threatened the future profitability of the group as a whole and added that the company is continuing to review its portfolio in the long term, with an expectation to reduce the number of House of Fraser stores over the next 12 months.

Debenhams’ Administration

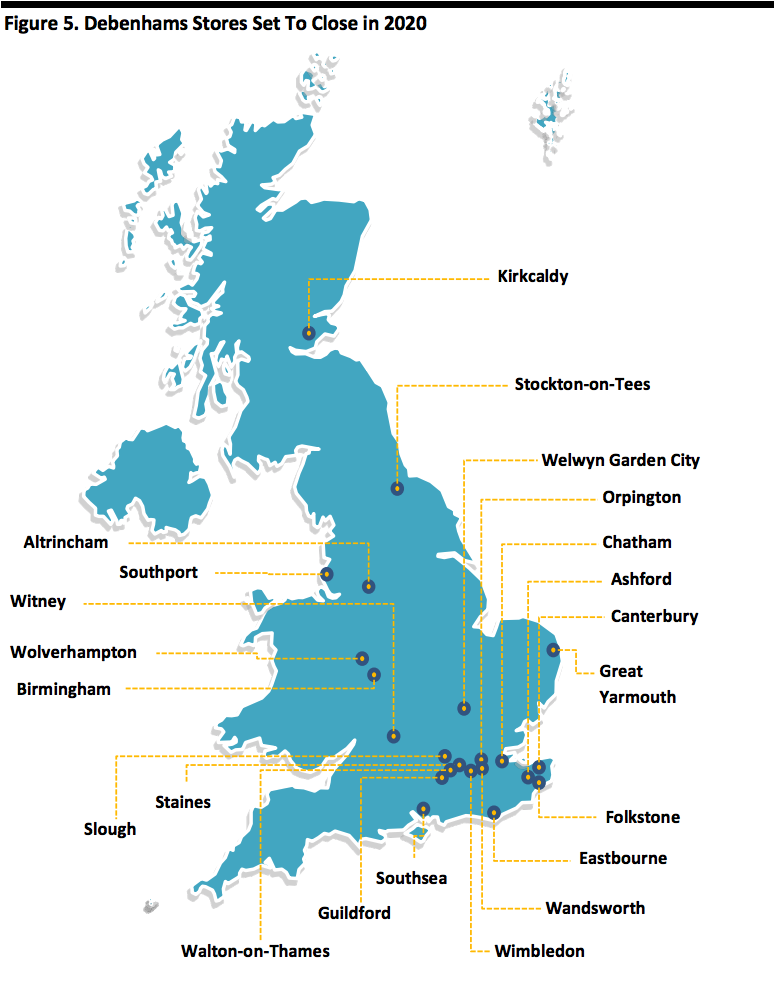

Debenhams has been struggling with formidable challenges, including high rents, falling sales and heavy competition. The company initially outlined plans to close 10 underperforming stores. However, as its finances continued to decline, the company revised this number to 50 in October 2018.

Where Did Debenhams Go Wrong?

Many Debenhams stores were tied up on long leases that were signed in 2003 to 2006 when the company was under private-equity . These long-term agreements held the company back from optimizing its store portfolio and implementing closures. Many of the prime-sited large stores came with high rents and high operating costs that included substantial staffing. The company’s UK occupancy costs (including rent, rates and service charges) accounted for £290 million in 2018.

Administration and After

In 2018, Debenhams’ finances deteriorated, and it issued three profit warnings in the year. Another profit warning was then issued in 2019 as sales continued to decline. In its 1H19 results, Debenhams reported statutory revenues of £1,246 million, a 5.5% decline year over year. Group EBITDA, before exceptional items, plunged 36.6% year over year to £65.9 million, and comparable sales were down 5.2% year over year. The company admitted that it would be unable to meet its previous forecasts for the current financial year due to a 6% slide in its UK sales and an increase in costs.

[caption id="attachment_99289" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

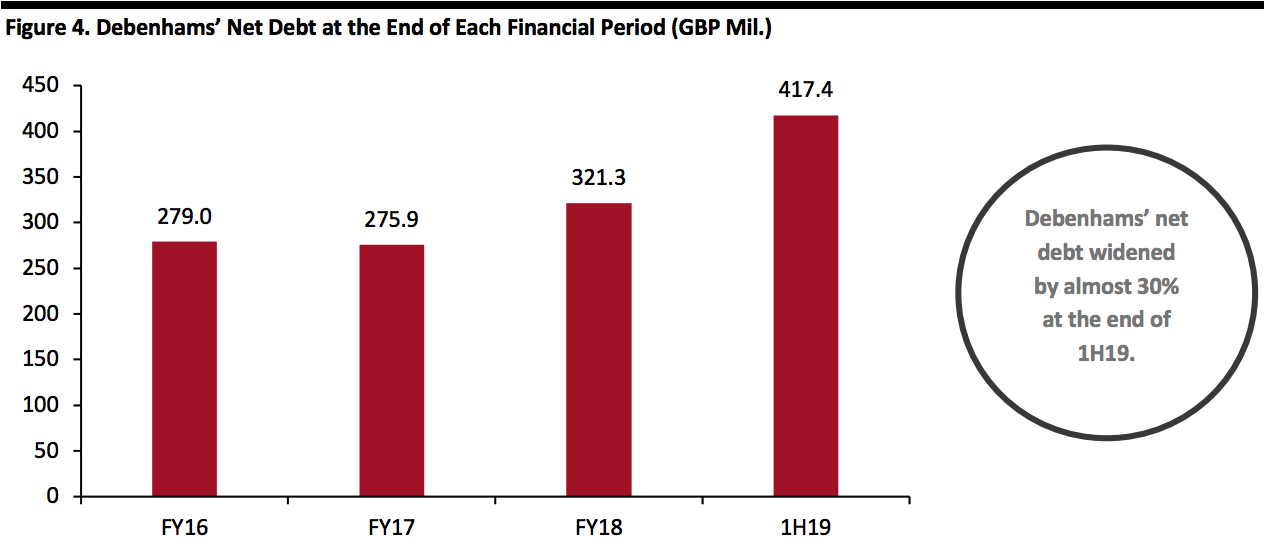

The company’s net debt piled up to £417.4 million as of March 2, 2019.

[caption id="attachment_99290" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

The company’s net debt piled up to £417.4 million as of March 2, 2019.

[caption id="attachment_99290" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

Debenhams rejected multiple takeover bids by Sports Direct and finally entered pre-pack administration in April 2019. The retailer was immediately bought out by Celine UK NewCo 1, a newly incorporated company that is owned by Debenhams’ lenders, including US hedge funds Silver Point and Golden Tree as well as Barclays and Bank of Ireland. Debenhams, under the new ownership, actively drove for a CVA insolvency procedure that would enable them to reduce rents with landlords and shut stores in the future. The company announced CVA proposals that divided the stores into three categories:

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Debenhams rejected multiple takeover bids by Sports Direct and finally entered pre-pack administration in April 2019. The retailer was immediately bought out by Celine UK NewCo 1, a newly incorporated company that is owned by Debenhams’ lenders, including US hedge funds Silver Point and Golden Tree as well as Barclays and Bank of Ireland. Debenhams, under the new ownership, actively drove for a CVA insolvency procedure that would enable them to reduce rents with landlords and shut stores in the future. The company announced CVA proposals that divided the stores into three categories:

- The lease will be retained at current rents for 39 stores.

- Rent reductions of approximately 50% will be applied to 22 stores until 1Q20, after which the stores are expected to close.

- The balance of the stores will have varying rent reductions in the range of 25-50%.

Source: Company reports[/caption]

In terms of management changes, Debenhams appointed its Chief Restucturing Officer, Stefaan Vansteenkiste, as CEO in August 2019, as part of its revival plans post administration. Vansteenkiste will succeed Sergio Bucher, who resigned from the position in April after the company was put into administration. In October, Debenhams appointed ex-CFO of House of Fraser Mark Gifford as its chairman. Gifford’s immediate task will be to assist Vansteenkiste in ensuring a successful festive performance in difficult trading conditions. Debenhams’ current lenders, which took control of the company post administration, agreed in October to inject a sum of £50 million to fund marketing and promotion activities for the company’s Christmas product ranges during the peak holiday trading period.

M&S’s Long-Term Struggles in Clothing and Home

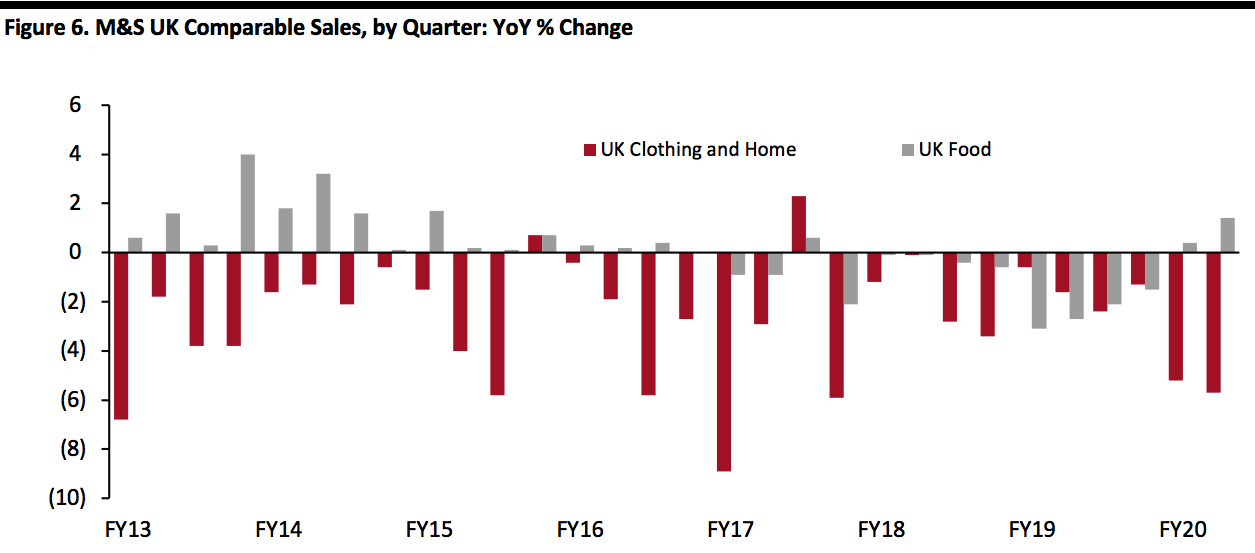

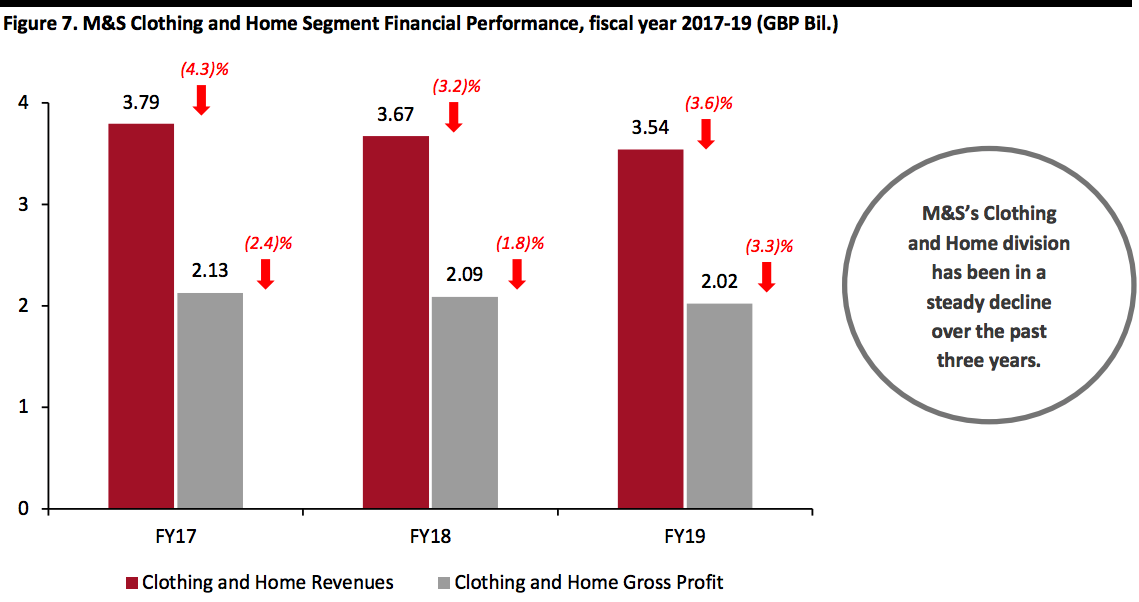

M&S’s UK clothing and home business has been declining for several years. As shown below, for a sustained period, its premium-positioned UK food business outperformed, but comparable sales growth has now turned negative in that division too.

[caption id="attachment_99292" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

In terms of management changes, Debenhams appointed its Chief Restucturing Officer, Stefaan Vansteenkiste, as CEO in August 2019, as part of its revival plans post administration. Vansteenkiste will succeed Sergio Bucher, who resigned from the position in April after the company was put into administration. In October, Debenhams appointed ex-CFO of House of Fraser Mark Gifford as its chairman. Gifford’s immediate task will be to assist Vansteenkiste in ensuring a successful festive performance in difficult trading conditions. Debenhams’ current lenders, which took control of the company post administration, agreed in October to inject a sum of £50 million to fund marketing and promotion activities for the company’s Christmas product ranges during the peak holiday trading period.

M&S’s Long-Term Struggles in Clothing and Home

M&S’s UK clothing and home business has been declining for several years. As shown below, for a sustained period, its premium-positioned UK food business outperformed, but comparable sales growth has now turned negative in that division too.

[caption id="attachment_99292" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Through 2Q20

Through 2Q20Source: Company reports[/caption] Where Did M&S Go Wrong? In apparel, M&S has been hit hard by structural shifts in retailing, as well as its inability to attract younger consumers and so replenish its customer base.

- M&S sits at the very middle of the apparel market and, as choice has boomed, the company has seen shoppers splinter away to a number of competing segments, from value retailers to online-only players and more premium rivals. The decline of the midmarket is a trend we have observed across countries and categories, and it is epitomized by the difficulties faced by M&S in fashion.

- In part because of this fragmentation, M&S’s remaining apparel shoppers are typically older; in 2016, Steve Rowe characterized the retailer’s core shopper as “Mrs M&S,” a woman in her 50s who shops with the company around 18 times per year. Over many years, the company has failed to attract younger customers. While M&S should not focus on pursuing fashion-conscious twentysomethings, it must look to replenish its shopper base by appealing to those in their 30s and 40s.

Source: Company reports[/caption]

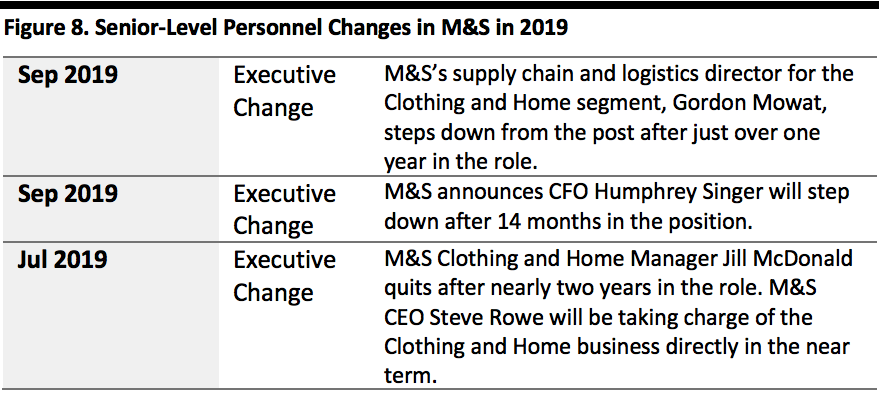

A string of recent personnel changes in upper management also underlines M&S’s difficulties:

[caption id="attachment_99294" align="aligncenter" width="500"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

A string of recent personnel changes in upper management also underlines M&S’s difficulties:

[caption id="attachment_99294" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

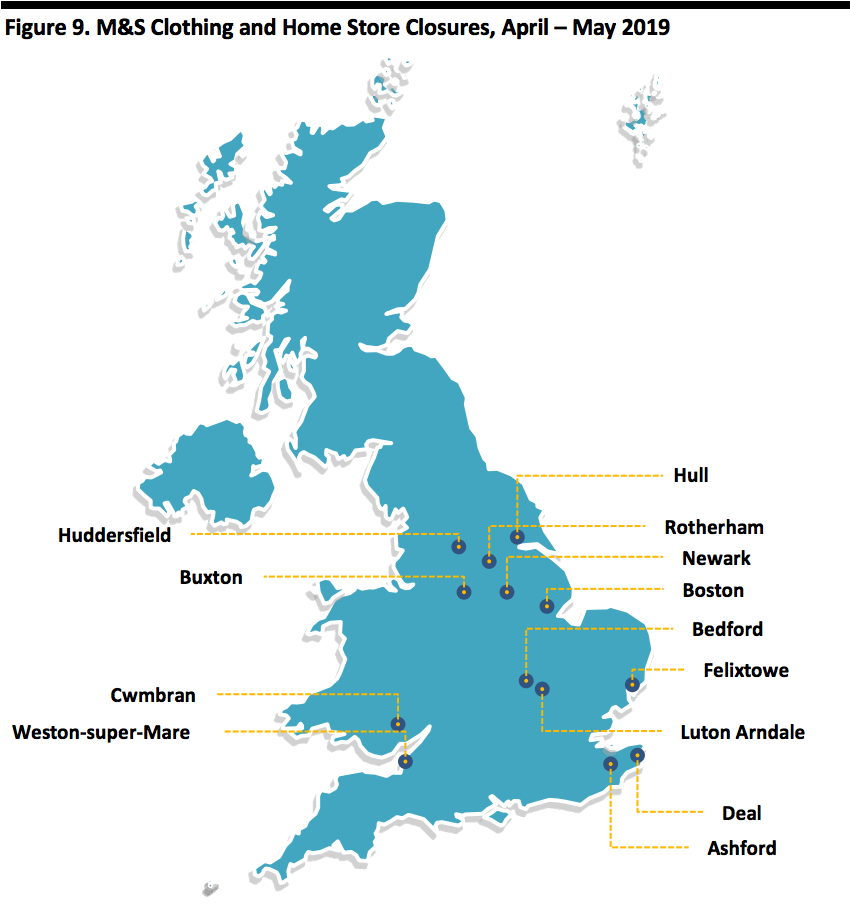

In May 2016, CEO Steve Rowe revealed a plan to improve the performance of clothing through everyday lower prices and fewer promotions, better product availability, fewer ranges and “unrivalled quality.” In November 2016, M&S announced its intention to rationalize its store estate over five years. The company confirmed plans to make changes that will affect more than 100 stores, accounting for 25% of its selling space. This will result in a net reduction of 10% of clothing and home space with 60 fewer full-line stores (which sell clothing, homewares and food). These changes include the closure of 30 full-line stores, and a further 45 will be downsized or replaced by Simply Food stores. Some new full-line stores will be opened in underserved areas.

Archie Norman, a veteran of retail turnarounds, joined as Chairman in September 2017. Subsequently, in November that year, M&S’s management announced a new five-year transformation plan, which includes a number of key strategies:

Source: Company reports[/caption]

In May 2016, CEO Steve Rowe revealed a plan to improve the performance of clothing through everyday lower prices and fewer promotions, better product availability, fewer ranges and “unrivalled quality.” In November 2016, M&S announced its intention to rationalize its store estate over five years. The company confirmed plans to make changes that will affect more than 100 stores, accounting for 25% of its selling space. This will result in a net reduction of 10% of clothing and home space with 60 fewer full-line stores (which sell clothing, homewares and food). These changes include the closure of 30 full-line stores, and a further 45 will be downsized or replaced by Simply Food stores. Some new full-line stores will be opened in underserved areas.

Archie Norman, a veteran of retail turnarounds, joined as Chairman in September 2017. Subsequently, in November that year, M&S’s management announced a new five-year transformation plan, which includes a number of key strategies:

- Focusing on becoming “the UK’s essential clothing retailer,” which includes lowering prices. The company has been lowering prices in apparel, including on entry-level products, and since 2016 has targeted greater full-price sales and less discounting.

- Accelerating the company’s UK Clothing and Home space rationalization plan. M&S had already announced plans to close, relocate or downsize 105 stores.

- Repositioning M&S’s UK Food business, which includes slowing the opening rate of Simply Food stores. M&S has repositioned its food business to broaden its appeal to family shoppers, including through lowering prices. The company acknowledged that its food business has become too premium and hence reduced the prices of over 400 of its most popular line. The retailer has also reduced its dependency on short-term promotions in addition to reducing overall promotional participation by over 10%.

- Becoming a digital-first organization, with the aim of generating one-third of Clothing and Home sales online by 2022. As of November 2017, 18% of sales in this category were made online.

- Reducing M&S’s cost base to become a lower-cost retailer

Source: Company reports[/caption]

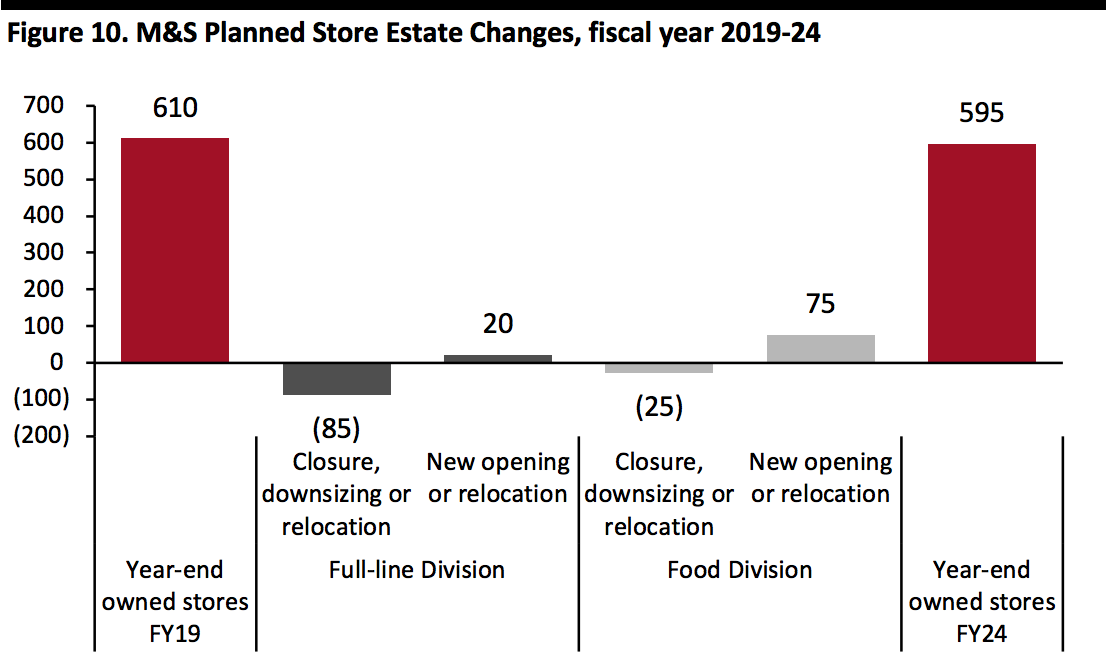

In May 2019, M&S announced that it will will close a further 85 department stores and 25 Simply Food outlets by fiscal year 2024. However, the company added that it will open 20 new full-line stores and 75 larger food stores.

[caption id="attachment_99296" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

In May 2019, M&S announced that it will will close a further 85 department stores and 25 Simply Food outlets by fiscal year 2024. However, the company added that it will open 20 new full-line stores and 75 larger food stores.

[caption id="attachment_99296" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

John Lewis Responses to Market Challenges

In October 2019, the John Lewis Partnership—owner of John Lewis department stores and the Waitrose grocery chain—announced plans to integrate the two businesses and slash jobs in order to cut costs. The company scrapped the positions of managing directors for each of the two chains, with Paula Nickolds, formerly Managing Director of the department store business, becoming Executive Director, Brand.

The announcement came less than one month after the department store business reported a £62 million adjusted operating loss for the half year ended July 27, 2019, down 220% from a £19 million loss in the prior-year period. The company cited soft demand in big-ticket categories, cost inflation and IT costs. Department store comparable sales were down 2.3% in the latest half year.

These changes were on top of previous cuts to staff bonuses, job cuts, the closure of one of its stores and the scrapping of a planned store opening.

Source: Company reports[/caption]

John Lewis Responses to Market Challenges

In October 2019, the John Lewis Partnership—owner of John Lewis department stores and the Waitrose grocery chain—announced plans to integrate the two businesses and slash jobs in order to cut costs. The company scrapped the positions of managing directors for each of the two chains, with Paula Nickolds, formerly Managing Director of the department store business, becoming Executive Director, Brand.

The announcement came less than one month after the department store business reported a £62 million adjusted operating loss for the half year ended July 27, 2019, down 220% from a £19 million loss in the prior-year period. The company cited soft demand in big-ticket categories, cost inflation and IT costs. Department store comparable sales were down 2.3% in the latest half year.

These changes were on top of previous cuts to staff bonuses, job cuts, the closure of one of its stores and the scrapping of a planned store opening.

Increasing Prevalence of CVAs

In its battle for survival, struggling department-store and apparel retail chains including Arcadia, Debenhams, House of Fraser and New Look have actively opted for a CVA insolvency procedure. A CVA is a UK insolvency law which allows the company and its creditors to come to a consensus for repayment of a portions of company’s debts over a specified period. Under CVA, a vote is held on the proposal which must be approved by more than 75% of firm’s creditors (voting by value). Once approved, it then becomes a legally binding agreement on the firm and its creditors including those who may not have agreed to it. The CVA enables the firms to slash their costs by opting to close underperforming stores (including those under long leases) or compelling the store landlords to accept rent reductions. There has been a substantial rise in the number of retailers in the UK using CVAs as a means to renegotiate rents or shut stores. Property group Colliers International reported that between 2017 and June 2019, a total of 954 stores were shut under the CVA route. The use of CVAs by retailers has attracted criticism and has proved unpopular with landlords. Property owners including British Land and Intu have claimed that poorly managed companies see CVA as a quick-fix tool to cut costs without needing to carry out more fundamental action to improve their businesses. In June 2018, The British Property Federation called on the UK government to conduct an independent urgent review of CVAs, arguing that the tool has been ‘misused’ by department store retailers to shed underperforming assets within a portfolio, enabling them to walk away from their lease liabilities without really addressing their wider problems. For example, British fashion and accessories retailer Monsoon Accessorize launched a CVA in July 2019 for rent reductions across 135 of its stores, citing a decline in sales, increased competition and subdued consumer spending. Monsoon’s use of a CVA to close stores and reduce rent liabilities was opposed by British Land (who voted against the deal), claiming that the company was nowhere close to collapse and that the structure of new funding provided by Monsoon owner Peter Simon was unsatisfactory.Key Insights

- Structural changes in the market have prompted difficulties at several major UK department stores. However, some large chains have seen self-inflicted wounds also. Internal factors include failure to embrace online trading opportunities early enough, poor management and investment decisions, and a failure to renew the customer base by appealing to younger shoppers.

- Major UK department-store retailers will continue to rationalize their portfolios and curtail their unproductive store footprint in the next three to five years. However, we believe that reviving the status of these chains will not be a smooth process.

- Retailers in this sector have already tried investing in digital, focusing on private labels and creating better in-store experiences—so far, these strategies have not been enough. We expect to see a leaner sector with fewer stores, even if not fewer chains. Department stores will have to review their business models, sharpen their positioning in a market crowded with choice, and put greater focus on their product and store innovation in order to secure their future in the market.

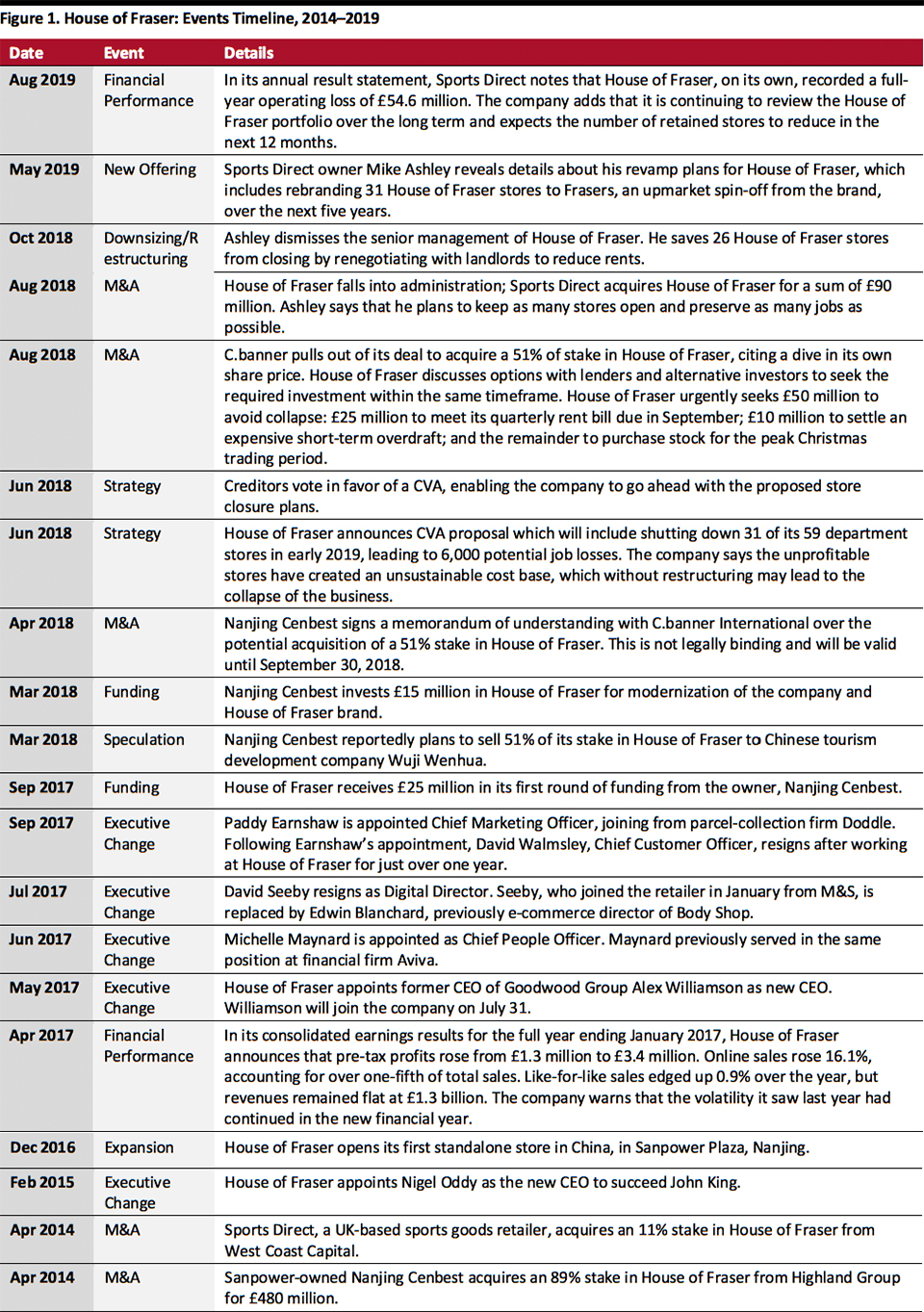

Appendix: Company Timelines

1. House of Fraser [caption id="attachment_99298" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports/Coresight research[/caption]

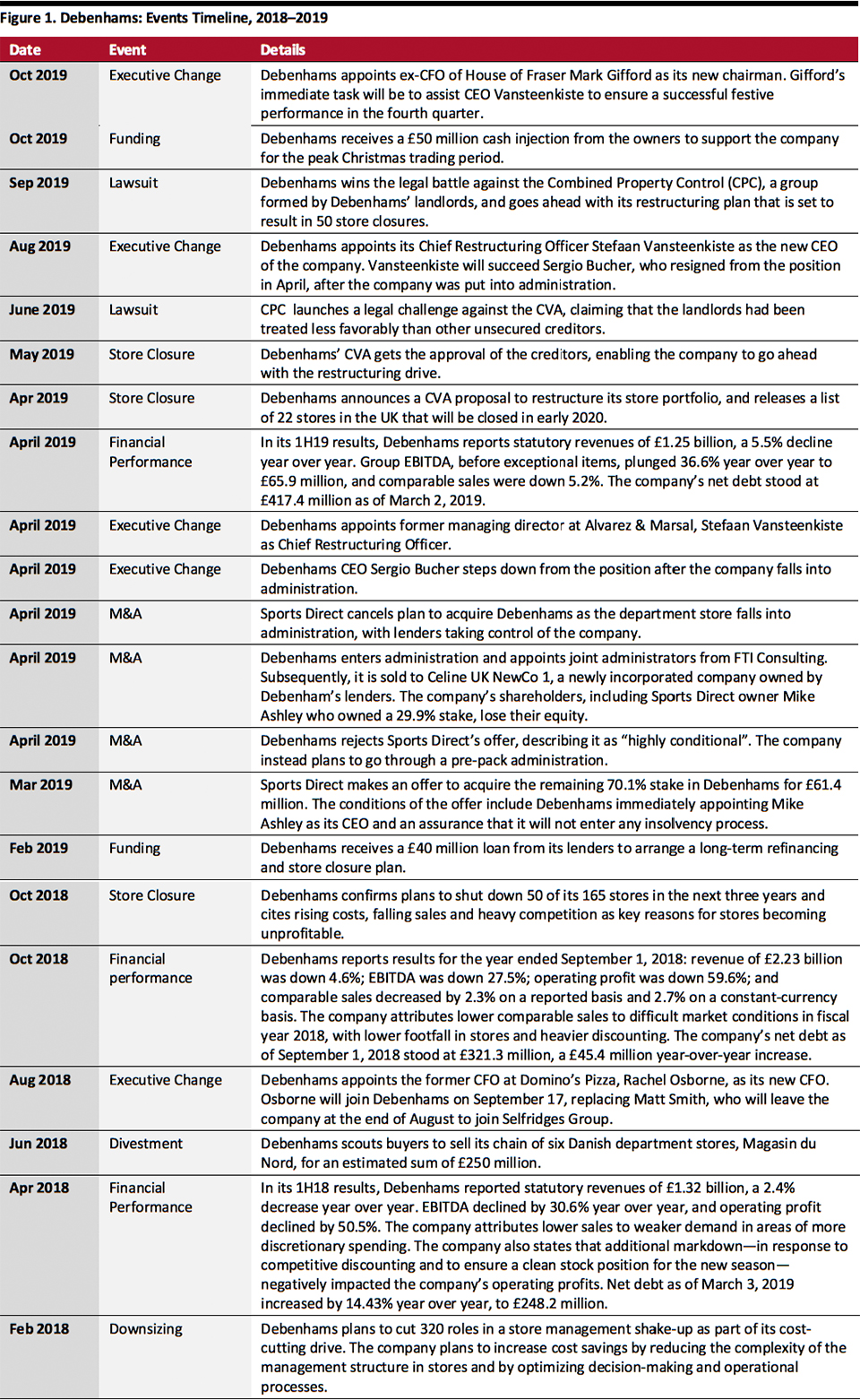

2. Debenhams

[caption id="attachment_99299" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports/Coresight research[/caption]

2. Debenhams

[caption id="attachment_99299" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports/Coresight Research[/caption]

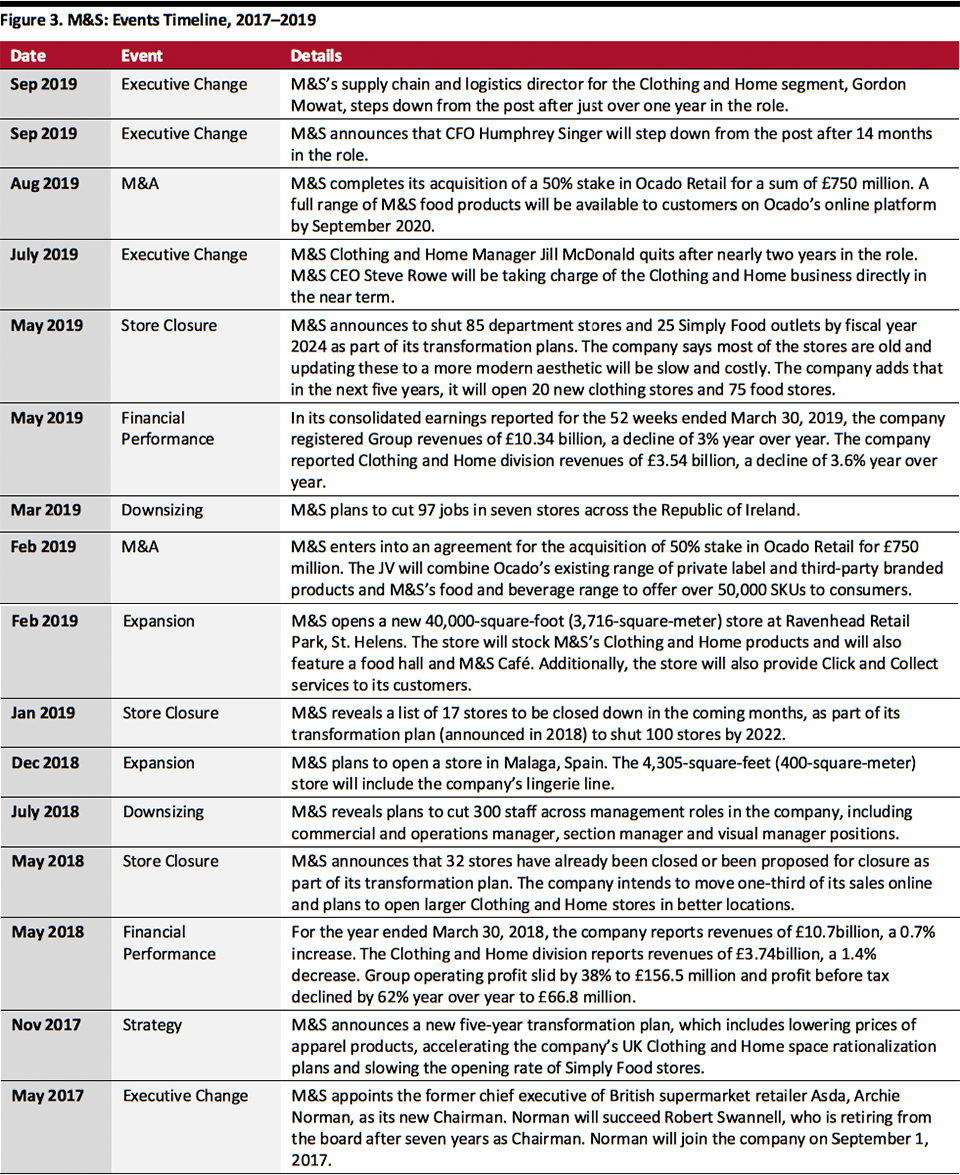

3. Marks and Spencer

[caption id="attachment_99300" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports/Coresight Research[/caption]

3. Marks and Spencer

[caption id="attachment_99300" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports/Coresight Research[/caption]

Source: Company reports/Coresight Research[/caption]