What’s the Story?

As e-commerce has made it easier to access to a wide range of branded apparel, a number of major clothing retailers in the UK and elsewhere in Europe are shifting their product mix to focus less on private-label apparel and more on brands. We look at this trend and its implications for retailers and vendors globally.

Why It Matters

A shift from private label to branded apparel in Europe is significant for the following reasons:

- It suggests further structural challenges for large, incumbent clothing retailers—typically private-label retailers.

- It implies further challenges for suppliers and sourcing intermediaries that sell to these retailers.

- Learnings from Europe are likely to be applicable elsewhere, given that structural shifts to e-commerce are universal.

- Major, struggling names in international retail continue to emphasize private label as an opportunity to turn around businesses—but these trends raise questions over the viability of private label as a demand generator.

The UK is a highly mature market for private-label clothing: Six of the country’s biggest clothing retailers—Arcadia, Asda, M&S, Next, Primark and Tesco—are wholly or overwhelmingly private-label retailers. We estimate that these six retailers accounted for one-quarter of all UK consumer spending on clothing and footwear in 2019 and that in total, private labels account for well over half of total UK clothing sales.

In the UK, the major channels for branded apparel have traditionally been multibrand department stores, online platforms such as Amazon and ASOS, and sportswear retailers. Typically, brands’ own brick-and-mortar stores and e-commerce sites each capture only a small market share. Off-price multibrand retail is limited to T.K. Maxx (the European name for the US’s T.J. Maxx), but this chain has been expanding. As elsewhere, department stores are capturing a declining share of clothing spend overall. We see a broadly similar picture in Germany, where department-store consolidation has occurred alongside the expansion of multibrand e-commerce platforms such as Zalando.

We consider private label to encompass companies that sell only through their own stores and websites and do not wholesale to third-party retailers. A more qualitative component is that the apparel tends to be visibly unbranded. Companies such as M&S, H&M and Primark fall within our definition of private-label retailers.

The Slow Decline of Private-Label Apparel in Europe: In Detail

It is not news that e-commerce has given consumers more choice than ever. Yet, the implications of this continue to crystalize—with one emerging as a potential heightened consumer preference for branded apparel. As brand accessibility has increased, store-based private-label market leaders can no longer rely on longstanding unique selling points such as proximity and product choice.

The Retreat from Private Label

- Late August 2020: The Chairman of John Lewis Partnership, Sharon White, told The Sunday Times that its namesake department stores would feature “less own-brand women’s fashion” because “mid-range, mid-price fashion is really hard to do when women are being more promiscuous, buying in so many different places—T.K. Maxx but also Zara and Selfridges.” Over a number of years and under different management teams, John Lewis had built up its private-label clothing collections. In early September 2020, the company announced the introduction of a roster of big-name brands in clothing, footwear, beauty and accessories, with 30 new brands including Athleta, Stella, Isle and Calvin Klein.

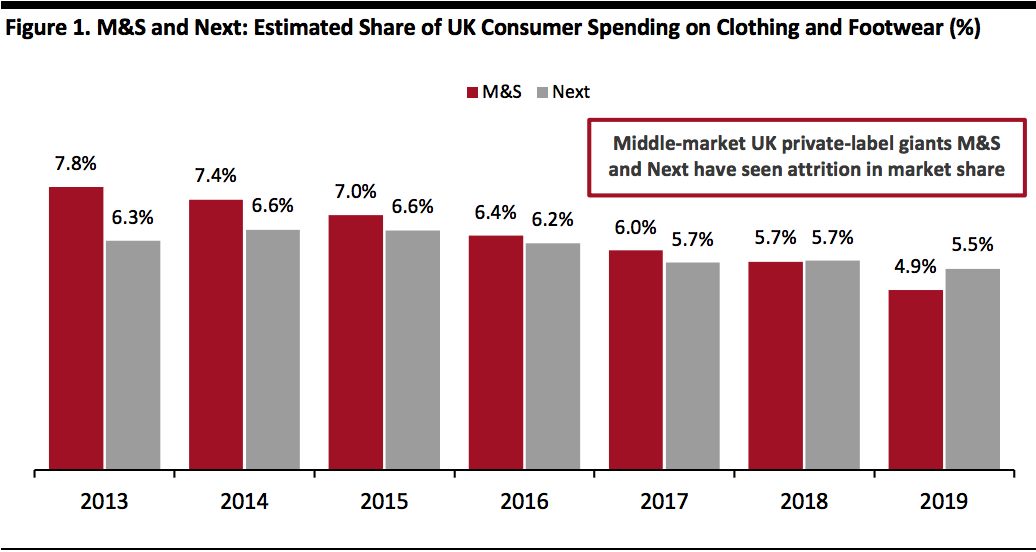

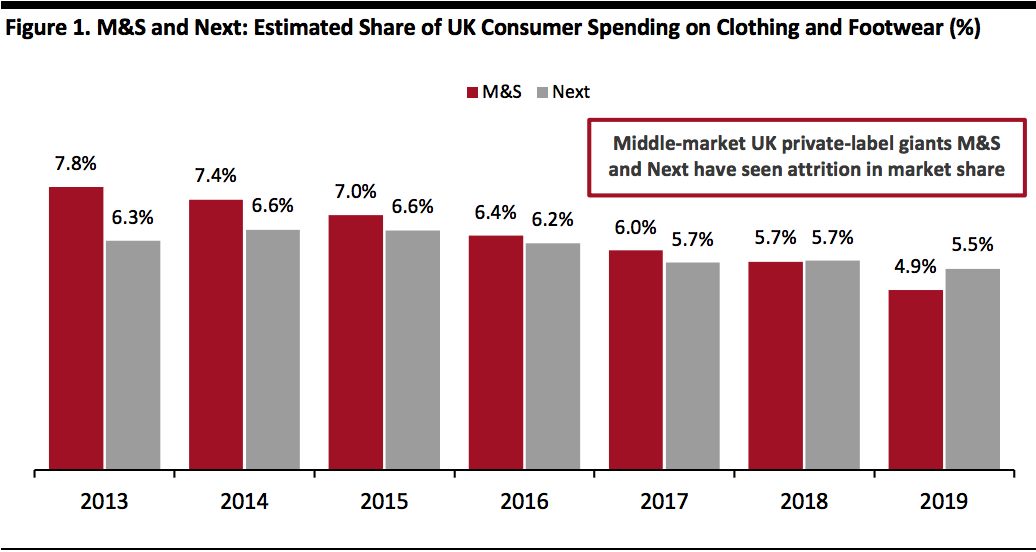

- May 2020: UK clothing stalwart M&S announced plans to add third-party fashion and home brands to its offering online and in selected stores. Up until now, M&S has been a 100% private-label retailer in apparel but has seen demand dwindle in an increasingly competitive market. We estimate that M&S lost the top spot in the UK clothing and footwear market to Next in 2019; see Figure 1 below for a breakdown of market share.

- 2019: Zalando axed its private-label division, zLabels, and cut its private-label offering to a core of “everyday essentials” in clothing, footwear and accessories. Zalando management noted that it had less need for a private-label collection as it has grown its branded assortment.

- 2014: Major private-label retailer Next launched its Label branded division online and, together with overseas sales, this has been a driver of Next’s total sales growth in the years since. In the year ended January 2020, the Label business grew full-price sales by 21.9%, compare to the Next brand’s UK full-price sales growth of 4.2%. The addition of new brands supported this growth, but sales of existing brands grew at a double-digit pace in the year, reflecting underlying demand for the offering.

- Mid 2010s: Stretching out our timeline, UK department store chain House of Fraser moved heavily into private labels, a period prior to its entry into administration in 2018—a strategy that we considered misjudged, given its more premium position in the market.

[caption id="attachment_116222" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Company reports/Office for National Statistics/Coresight Research

Source: Company reports/Office for National Statistics/Coresight Research[/caption]

Impacts of Weak Demand

A counterbalance to arguments that private labels can help save department stores is the example of Debenhams—which had long since reduced its branded apparel offering in favor of an ultimately tired and undistinguished private-label clothing offering. Flailing Debenhams has twice filed for administration (akin to bankruptcy) and is currently seeking a buyer or investor in an apparently last-ditch bid to avoid liquidation.

Possibly a further indication of weak demand for unbranded apparel,

H&M has been hit by softer underlying demand in recent years and since 2018 has been refocusing on improving digital experiences, reforming its supply chain and, most recently,

closing stores.

The Exception Lies at the Bottom of the Market

The exceptions to this trend tend to be at the bottom of the market— including names such as Boohoo.com (online) and Primark (in-store). Both are outpacing rivals with 100% private-label offerings at bargain prices. Unlike in the middle of the market, we see consumers being much more willing to trade brand names for value at the lowest end of the market.

In addition, retailers with very strong fashion credentials may be more immune. By our definition, Zara is a private-label retailer—but it is one that retains the credentials of a brand and continues to outperform most major rivals.

What We Think

Implications for Brands and Retailers

- Our examples are from Europe—a mature private-label market—but could ultimately be mirrored in markets such as the US, given that underlying shifts in consumer behavior, especially related to e-commerce, are fundamentally the same.

- It is increasingly tenuous for hard-hit department stores to point to private label as a key plank of a turnaround strategy—in Europe, but potentially elsewhere, too. We note that US department stores, such as Macy’s, have long been pushing private label as a savior of their businesses, and we see the trends outlined in this report raising questions over the viability of such moves.

- Monobrand retailers can migrate to multibrand models, as Next in the UK has illustrated. The tradeoff is that they are likely to see meaningfully lower margins on branded offerings. For long-term survival, we would urge such retailers to look past such concerns.

Implications for Vendors

- The apparent decline of private-label clothing in Europe is possibly a harbinger of trends in the much bigger US market. That is bad news for global apparel vendors and sourcing intermediaries that have built businesses on supplying private-label apparel to mass-market names in retail.

- In Europe and elsewhere, structural declines in private label would compound the challenges associated with supplying hard-hit centerground retailers, such as department stores. Apparel vendors and sourcing intermediaries must continue to seek to diversify their customer bases.

- Private-label opportunities exist at the very bottom of the market—but this implies lower margins and, in some cases, the risk of reputational damage, given the poor compliance records of some budget apparel names.

Source: Company reports/Office for National Statistics/Coresight Research[/caption]

Impacts of Weak Demand

A counterbalance to arguments that private labels can help save department stores is the example of Debenhams—which had long since reduced its branded apparel offering in favor of an ultimately tired and undistinguished private-label clothing offering. Flailing Debenhams has twice filed for administration (akin to bankruptcy) and is currently seeking a buyer or investor in an apparently last-ditch bid to avoid liquidation.

Possibly a further indication of weak demand for unbranded apparel, H&M has been hit by softer underlying demand in recent years and since 2018 has been refocusing on improving digital experiences, reforming its supply chain and, most recently, closing stores.

The Exception Lies at the Bottom of the Market

The exceptions to this trend tend to be at the bottom of the market— including names such as Boohoo.com (online) and Primark (in-store). Both are outpacing rivals with 100% private-label offerings at bargain prices. Unlike in the middle of the market, we see consumers being much more willing to trade brand names for value at the lowest end of the market.

In addition, retailers with very strong fashion credentials may be more immune. By our definition, Zara is a private-label retailer—but it is one that retains the credentials of a brand and continues to outperform most major rivals.

Source: Company reports/Office for National Statistics/Coresight Research[/caption]

Impacts of Weak Demand

A counterbalance to arguments that private labels can help save department stores is the example of Debenhams—which had long since reduced its branded apparel offering in favor of an ultimately tired and undistinguished private-label clothing offering. Flailing Debenhams has twice filed for administration (akin to bankruptcy) and is currently seeking a buyer or investor in an apparently last-ditch bid to avoid liquidation.

Possibly a further indication of weak demand for unbranded apparel, H&M has been hit by softer underlying demand in recent years and since 2018 has been refocusing on improving digital experiences, reforming its supply chain and, most recently, closing stores.

The Exception Lies at the Bottom of the Market

The exceptions to this trend tend to be at the bottom of the market— including names such as Boohoo.com (online) and Primark (in-store). Both are outpacing rivals with 100% private-label offerings at bargain prices. Unlike in the middle of the market, we see consumers being much more willing to trade brand names for value at the lowest end of the market.

In addition, retailers with very strong fashion credentials may be more immune. By our definition, Zara is a private-label retailer—but it is one that retains the credentials of a brand and continues to outperform most major rivals.