Executive Summary

As e-commerce continues to grow, consumers’ expectations rise and competition persists, last mile becomes an increasingly crucial component of supply-chain logistics. The expansion of e-commerce continues to accelerate. According to Statista, from 2014 to 2017 the global retail e-commerce market grew by 72% to $2.3 trillion and sales are expected to reach $4.9 trillion by 2021. Clearly, more and more packages are being delivered. At the same time, consumers have come to expect rapid and convenient service, with shipping costs and delivery times an important factor in their purchasing decisions. Retailers and logistics providers, vying for market share and looking to minimize costs, have responded by investing in last-mile innovation and infrastructure.

This report covers three aspects of last-mile logistics: transportation, delivery and reverse logistics.

1) Transportation

We evaluate how innovations in transportation may supplement or replace the existing model, whereby trucks and drivers transport goods from local warehouses to their destinations.

- Human Delivery: Retailers and logistics providers are using contracted workers to deliver packages, enabling flexible capacity.

- Robotics Technology: Robotics companies are developing and testing unmanned ground vehicles to deliver packages.

- Drone Technology: Drone makers are experimenting with delivery via unmanned aerial vehicles, but face numerous barriers including regulatory restrictions.

2) Delivery

We explore solutions to ease the actual delivery, commonly referred to as “last 100 feet logistics,” so packages can be conveniently and securely transferred to the hands of consumers.

- Smart Locks: Smart lock technology has enabled in-home delivery, but consumer sentiment and concerns over theft and privacy are hurdles to adoption.

- Secure Lockers Secure lockers eliminate the need for the recipient to be present at delivery, and allow customers to retrieve packages at all hours. Lockers installed in local shops can be mutually beneficial, bringing efficacy to the seller, convenience to the buyer and foot traffic to the shops.

3) Reverse Logistics

Finally, we look at reverse logistics to see how the industry aims to better accommodate returns.

- Return Hubs: Two-way smart lockers and return counters in local stores ease the process of returns for customers. Some third-party retailers with physical footprints are willing to host return hubs to help drive foot traffic.

- Return Prevention: Although consumers increasingly expect free delivery, which helps drive purchasing, retailers are testing incentives to limit returns. Additionally, advances in sizing and fit tools can help curb apparel returns.

- Return Incorporation: Rather than combat returns, some retailers have embraced two-way logistics in their business models as core value propositions.

Throughout, we analyze established companies and hopeful startups pioneering the last mile.

Introduction to Last-Mile Logistics

Last-mile logistics refers to the final steps of the supply chain, encompassing the journey of goods from a centralized hub to their final destination. In e-commerce, this typically means movement from a local warehouse to a home, and is accomplished using delivery trucks and drivers

Last-mile logistics is a particularly costly segment of the supply chain, as aggregation synergies are dissolved and each package is routed to a separate destination. In addition to cost considerations, trends in e-commerce are driving massive delivery volumes.

According to 2016 data by Honeywell and published by BI Intelligence, last mile accounted for 53% of delivery costs, surpassing line haul, sorting and collection. And, according to data compiled by Kleiner Perkins for its Internet Trends report, the big three US delivery companies—USPS, UPS and FedEx—delivered nearly 11 billion packages in 2017, compared with fewer than 8 billion packages in 2012, suggesting a growth rate of approximately 38% over the five-year period.

Costs and volumes are perhaps the biggest issues, but numerous challenges underpin last-mile logistics including theft, repeat delivery attempts, inclement weather, rough terrain, distance between properties, consumer sentiment, regulatory restrictions, trained labor and irregular demand. While these challenges complicate last-mile logistics, they also present exciting opportunities for innovation at every step.

Major Players Investing in Last-Mile Logistics

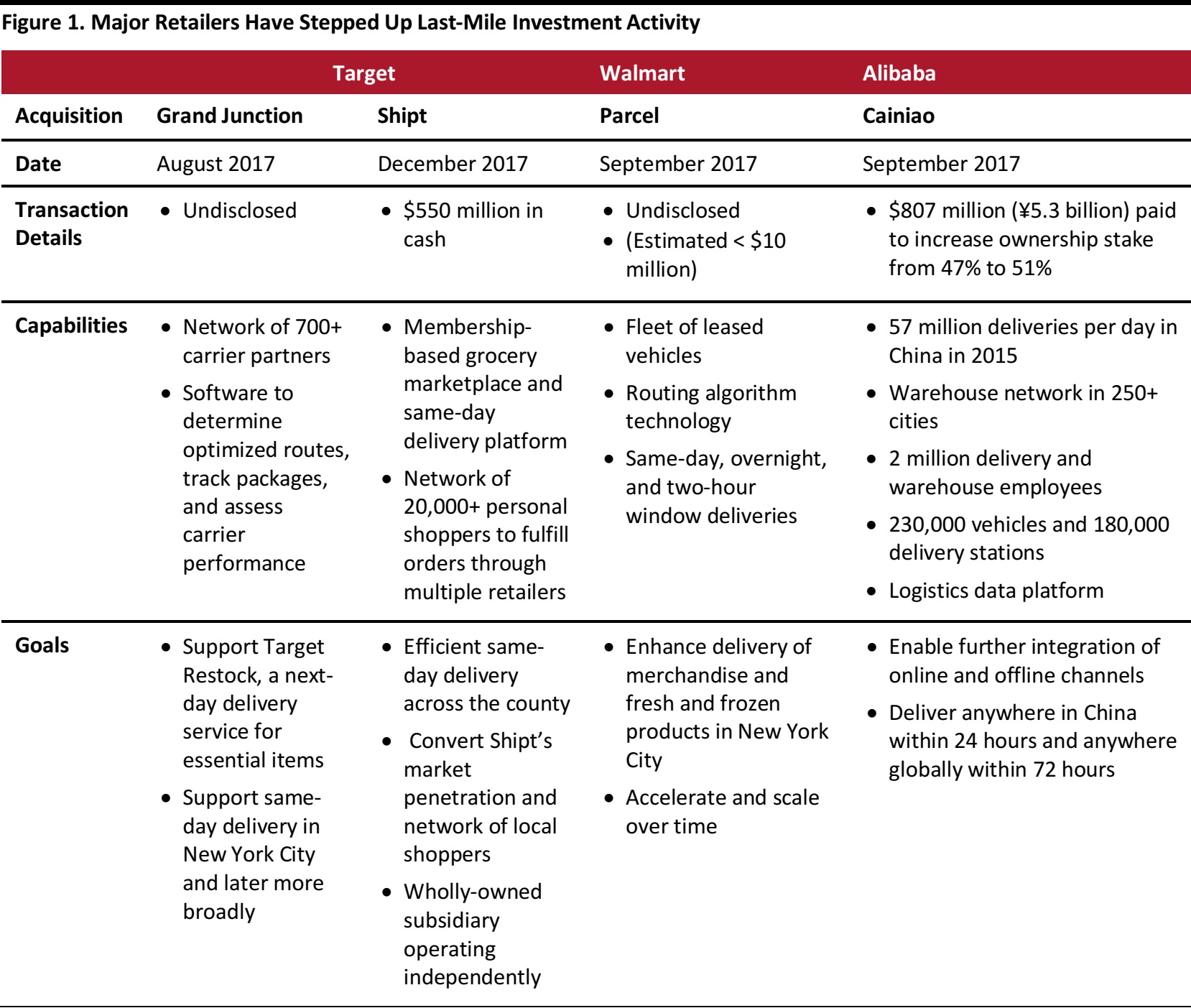

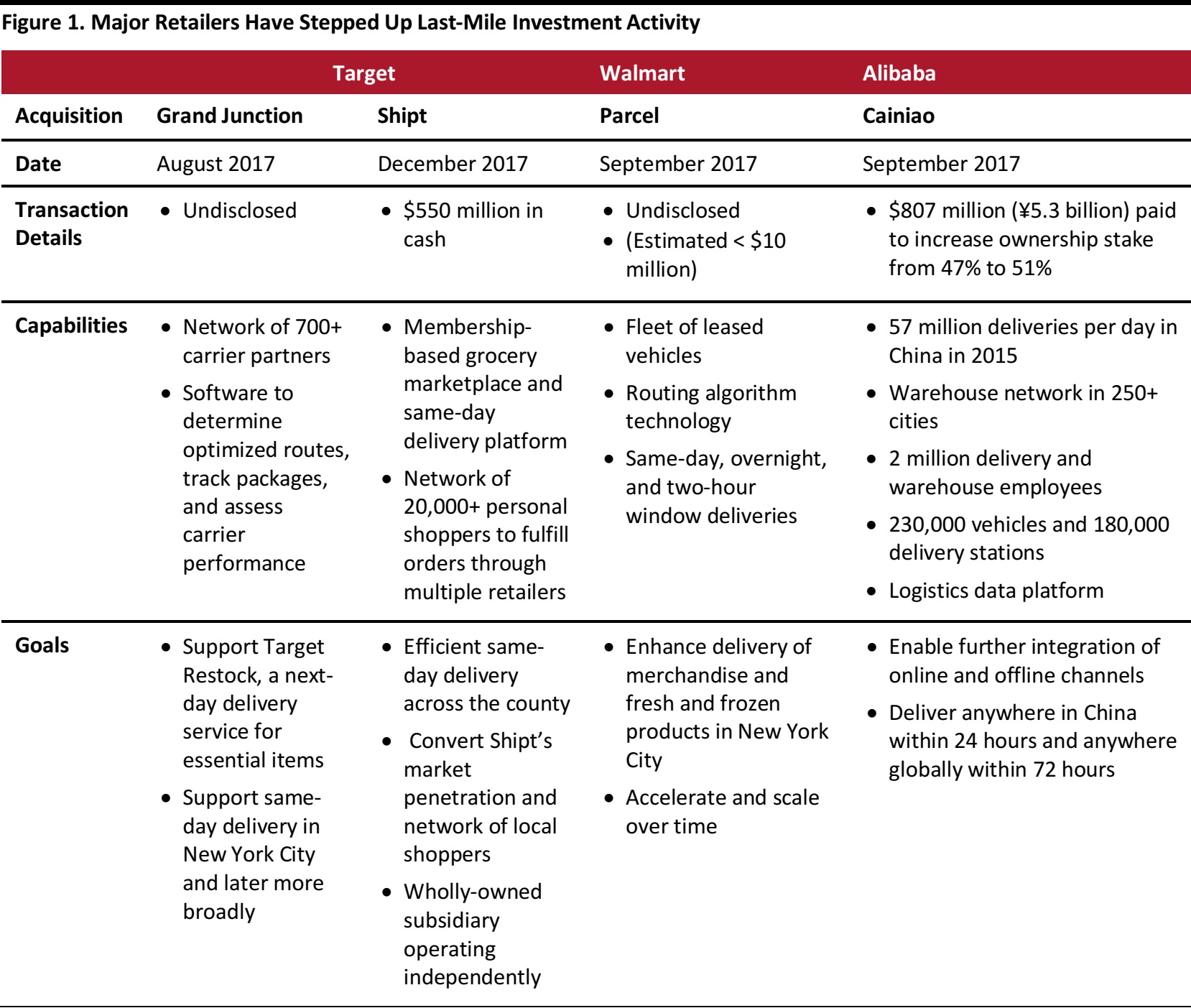

Recent acquisitions by leading retailers and logistics providers signal the importance of last-mile logistics solutions. Since 2017, Target, Walmart and Alibaba have each made major investments to enhance their delivery capabilities. Much of this activity is an attempt to ward off Amazon’s growing domination as it gains market share, drives free shipping through Amazon Prime membership subscriptions and looks to bring logistics capabilities in house. For retailers offering similar products, optimized logistics are not merely a necessary component of operations, but a key point of differentiation on which their businesses may thrive or decline.

Source: Company reports

These acquisitions each offer both logistics infrastructure and optimization software. This combination is crucial for ensuring packages are delivered quickly, conveniently and cost-effectively. Retailers with logistics efficiency can meet high customer expectations and remain competitive on price.

In addition to acquisitions, these and other major retailers are investing heavily in internal research and development (R&D) to enhance last-mile logistics capabilities.

Amazon is working to bring logistics services in-house, in part by building a network of partners that have started their own delivery businesses to serve Amazon exclusively. Furthermore, Amazon’s 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods opens last-mile logistics opportunities by adding 487 physical locations that can serve as distribution hubs.

JD.com, one of the largest online retailers in China, has built a logistics network from scratch, and is now equipped to serve a population of over 1 billion with same-day or next-day delivery. The company continues to pursue automation technology and other innovations through its JD Logistics arm, which also caters to third-party sellers.

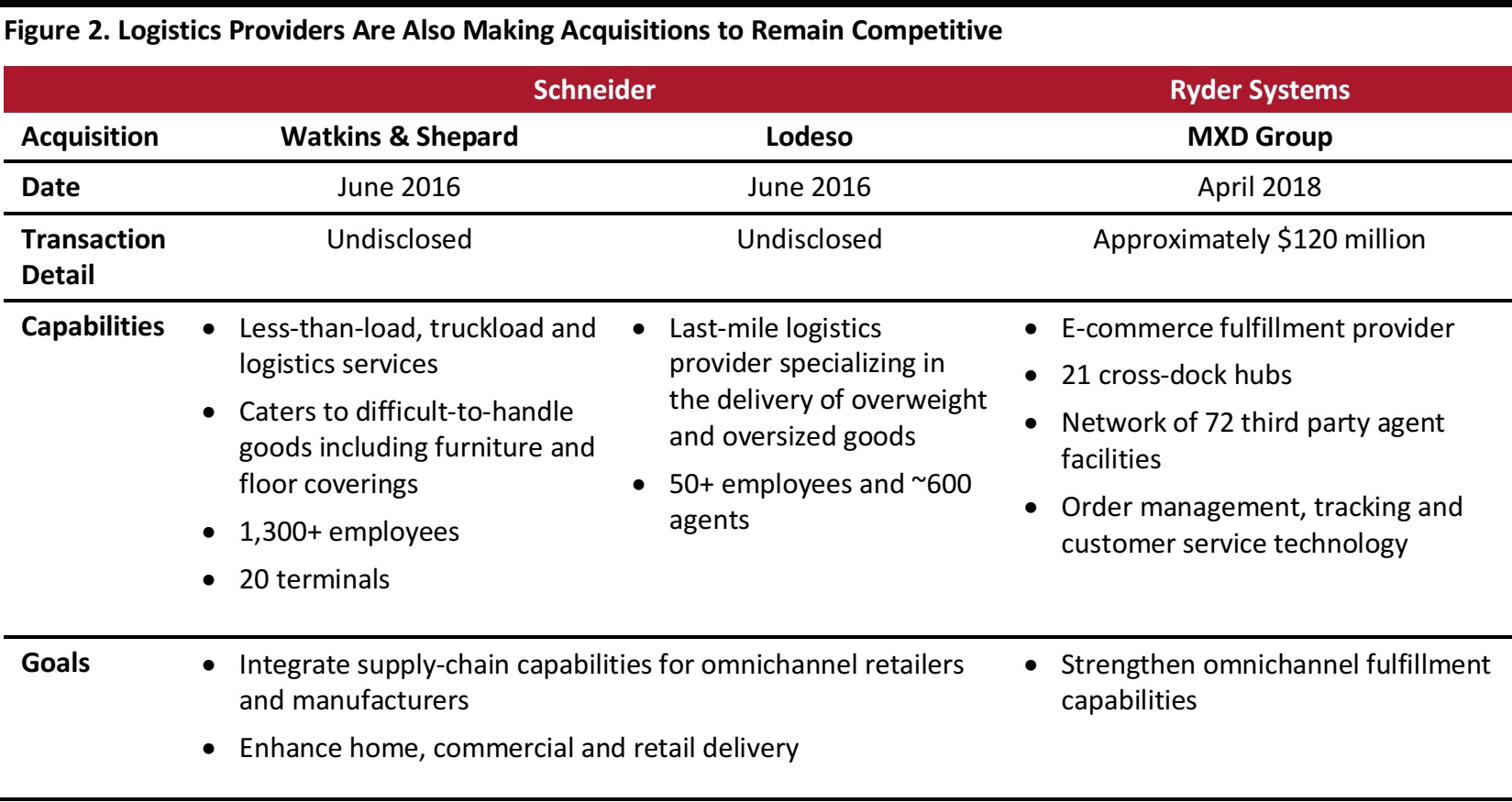

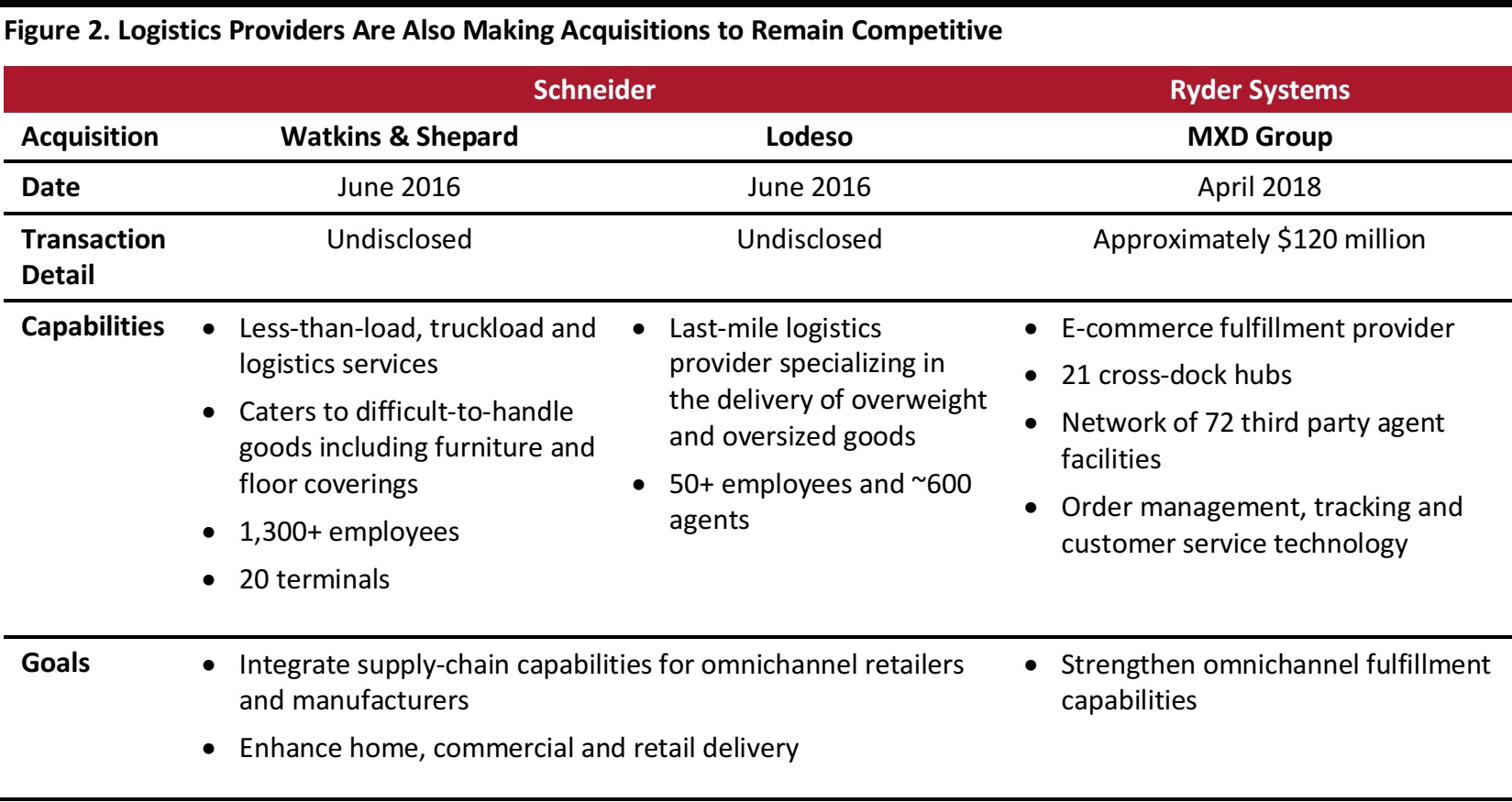

Retailers are not the only big investors in last mile capabilities. Longstanding logistics companies including Schneider and Ryder Systems have also made recent acquisitions to remain relevant.

Source: Company reports

Transportation Innovation

How goods get from point A to point B significantly defines last-mile logistics, impacting speed, degree of uncertainty, convenience and labor costs. Today, goods are typically delivered from a centralized warehouse to individual consumers via delivery trucks and drivers. But new models for flexible workers and advances in automation, particularly drone and robotics technology, are shaping the future of last-mile delivery.

Human Delivery

On-demand models have taken off in the meal-delivery segment, with companies such as Seamless, Caviar, Postmates, Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Doordash, Delivery Hero, Ele.me and Meituan-Dianping out on the streets. These services use bike messengers and independent drivers to deliver meals in under an hour. Similar models of contracted and flexible labor have broader application to the last-mile delivery industry and are being pursued by multiple players.

Startups

Deliv provides a same-day delivery solution to retailers and businesses. The company currently serves 35 markets and aims to make deliveries in as fast as an hour, relying on a network of individual couriers who are rated on performance. Clients include Macy’s, Bloomingdales, Bloom That, Best Buy, Office Depot and PetSmart, along with small businesses and individuals. The company also has a partnership with Walmart, helping to power the retailer’s grocery delivery service.

Deliv solves issues of irregular demand by allowing flexible capacity; an apparel retailer can transfer inventory to a nearby location without sacrificing an employee; a bakeshop is able to double its holiday delivery business; and a store with two locations but only one van can increase profits and enhance customer service—all at lower costs than via traditional delivery providers.

The company was founded in 2012 and has received $40.4 million in funding from investors including Upfront Ventures, RPM Ventures and UPS Strategic Enterprise Fund. In 2015, Deliv acquired Zipments, which it continues to operate as a distinct brand in Manhattan. In 2018, the company launched Deliv Rx to enable same-day delivery of prescriptions. The company also has a partnership with August Home, detailed later.

Source: Deliv

Hitch is building a crowdsourced solution for same-day delivery. The company operates an app that connects shippers with travelers who are already headed along a package’s intended route. Whether lending a tennis racket to a friend, gifting birthday flowers to a relative across town, or sending a signed document to a lawyer, Hitch eliminates a trip to the shipping store and aims to reduce costs.

Hitch targets person-to-person delivery, but could have enterprise applications if operated at scale. For example, a person who works near a distribution facility could pick up packages on their way home from the office and deliver them to their neighbors on behalf of the retailer. The company was founded in 2014 and has not disclosed funding.

Big Retailers

Amazon is exploring new models for manual delivery. Shipping costs as a percentage of net sales have increased from 10.7% in 2015 to 12.2% in 2017, and have grown significantly on an absolute basis as the company has scaled, increasing from $11.5 billion in 2015 to $21.7 billion in 2017. Much of these costs can be attributed to last mile.

The company aims to innovate at the tail end of the supply chain, in part by experimenting with bringing last-mile logistics in-house. Amazon Flex was launched in 2015 and now operates in more than 50 cities, paying flexible workers $18–$25 per hour to deliver packages. More recently, the company began a program that supports entrepreneurs in launching businesses to deliver Amazon packages. Amazon Delivery Service Partners can start these small businesses for as little as $10,000, with Amazon providing technology and logistics expertise along with other support. Owners are expected to operate 20–40 vans with 40–100 employees and are responsible for building teams and managing operations.

Source: Amazon

Walmart has also experimented with delivery to fend off e-commerce competition, although it recently shut down a pilot program in last-mile logistics. The terminated program was announced in June 2017 and aimed to leverage Walmart’s vast contingent store staff to make deliveries on their way home from shifts. Pilots were conducted in two stores in New Jersey and one store in Arkansas, but saw little success. Employees, who lacked logistics expertise, expressed concerns about time, pay, use of personal cars and insurance, and potential responsibility for damaged or lost goods.

In-Store Pickup

On the flip side of delivery, retailers are also offering in-store pickup for purchases made online. This offering eliminates the last-mile delivery burden for sellers and can also be advantageous to the customer by allowing quick access.

Walmart offers in-store pickup for grocery orders at approximately 1,800 locations in the US and plans to expand to more stores. In August 2018,

Amazon announced a grocery pickup service at Whole Foods locations in Sacramento and Virginia Beach for orders placed through Prime Now. The service is free for orders over $35 and available within one hour, or customers can pay $4.99 for service within 30 minutes.

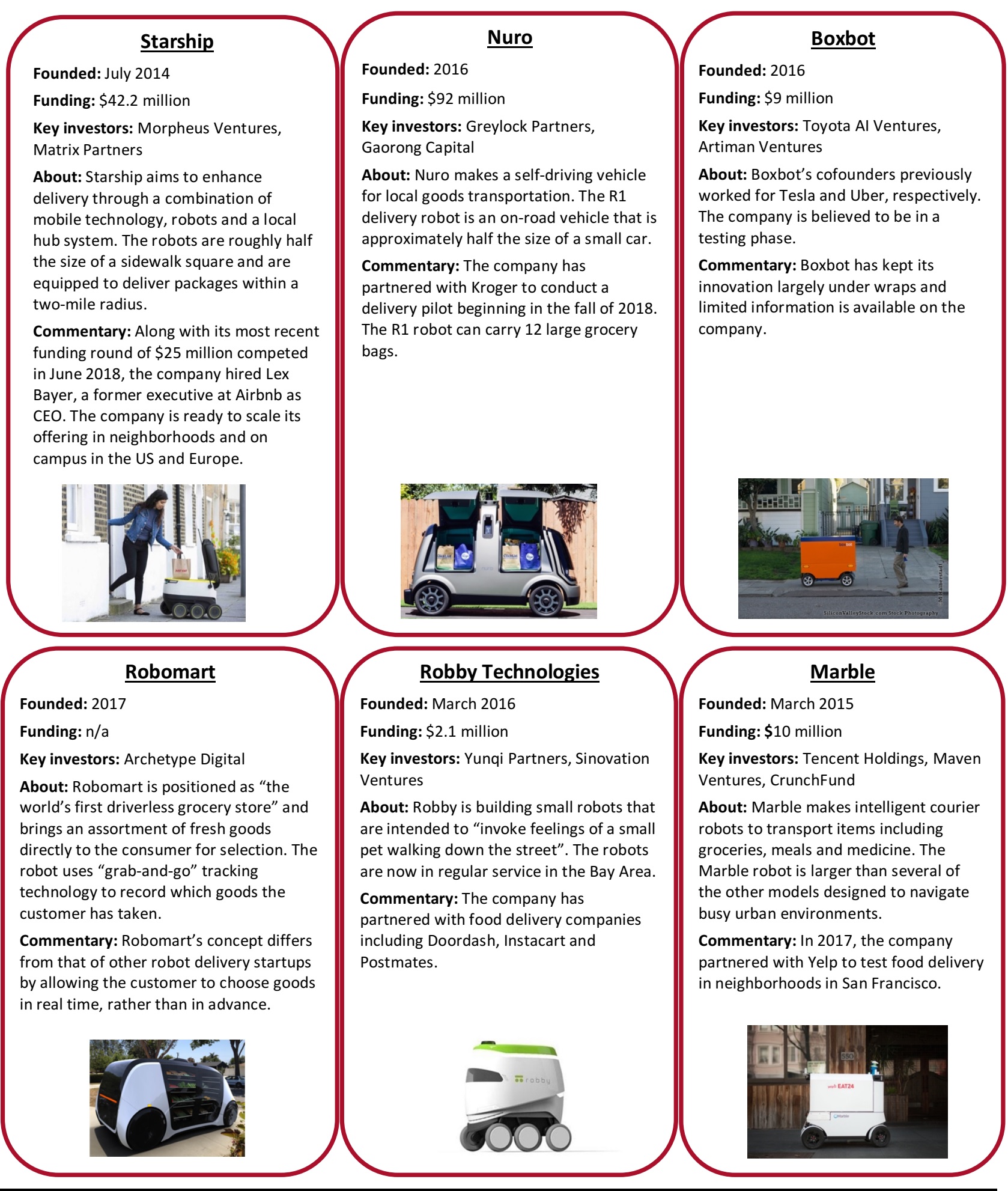

Robotics Technology

Advances in robotics technology may also add efficiency to last-mile logistics. Imagine a friendly, wheeled robot rolling down the sidewalk to deliver a pizza, or a boxcar robot pulling into a driveway with a full load of groceries. This is the ambition of multiple robotics startups and big retailers innovating in-house.

According to a 2018 report by Zion Market Research, the global autonomous robot market was valued at approximately $4.6 billion in 2016, and is expected to reach $11.9 billion by 2024, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14%. On a volume basis, demand for autonomous robots is expected to grow at a 13% CAGR to reach 115,400 units by 2024.

Much of this forecasted market expansion is attributed to growing demand for unmanned ground vehicles, which comprised more than 50% of the overall autonomous robot market as of 2016. McKinsey estimated in 2016 that autonomous vehicles will eventually deliver 80% of parcels, and believes there will be a transformation towards this reality within 10 years. This transformation depends on innovating, shifting consumer sentiment to favor or tolerate new technologies and overcoming regulatory hurdles, which McKinsey suggests will be driven by large automobile companies.

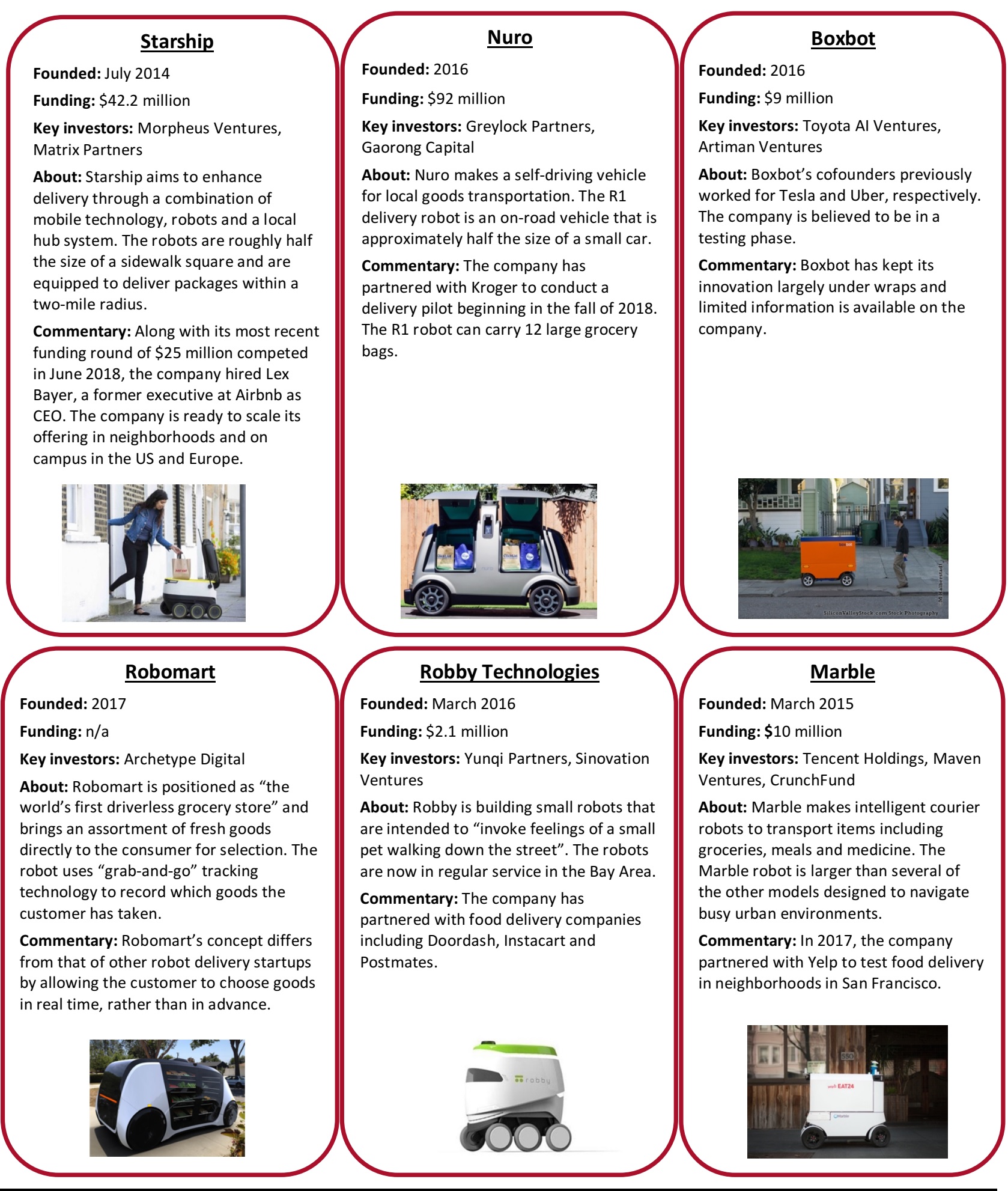

Source: Company reports, Crunchbase

Big Retailers

Robotics innovation is also occurring within big retailers.

In January 2018,

Amazon published a patent for an autonomous ground vehicle to be based at delivery locations. According to the application, the vehicle is designed to retrieve items from transportation vehicles for delivery to specified locations. In practice, perhaps the vehicle will be kept in a consumer’s garage and will roll down the driveway to collect packages from delivery trucks. The vehicle will then return to the home with the ability to unlock the door and deliver the item securely. Amazon envisions the vehicle being owned by a single user, or providing a shared service to a neighborhood or apartment building.

JD.com began limited robot delivery in Beijing in June 2018, and is focused primarily on reducing labor costs associated with last-mile delivery.

Through its logistics arm Cainiao,

Alibaba is also working on robotics delivery. In May 2018, the company debuted the G Plus, a road-going delivery robot that uses laser technology for navigation. This technology differs from prototypes by other developers, which typically use cameras and radar to move around. The project has been conducted in collaboration with Chinese company RoboSense, which provides LIDAR (light detection and ranging) technology. Facial recognition capabilities are also installed to ensure authorized receipt. The bot moves relatively slowly, under 10 miles per hour, but is comparatively large and equipped to carry numerous packages. The company is testing the G Plus at its headquarters in Hangzhou, China and hopes to begin production in late 2018.

Source: Cainiao

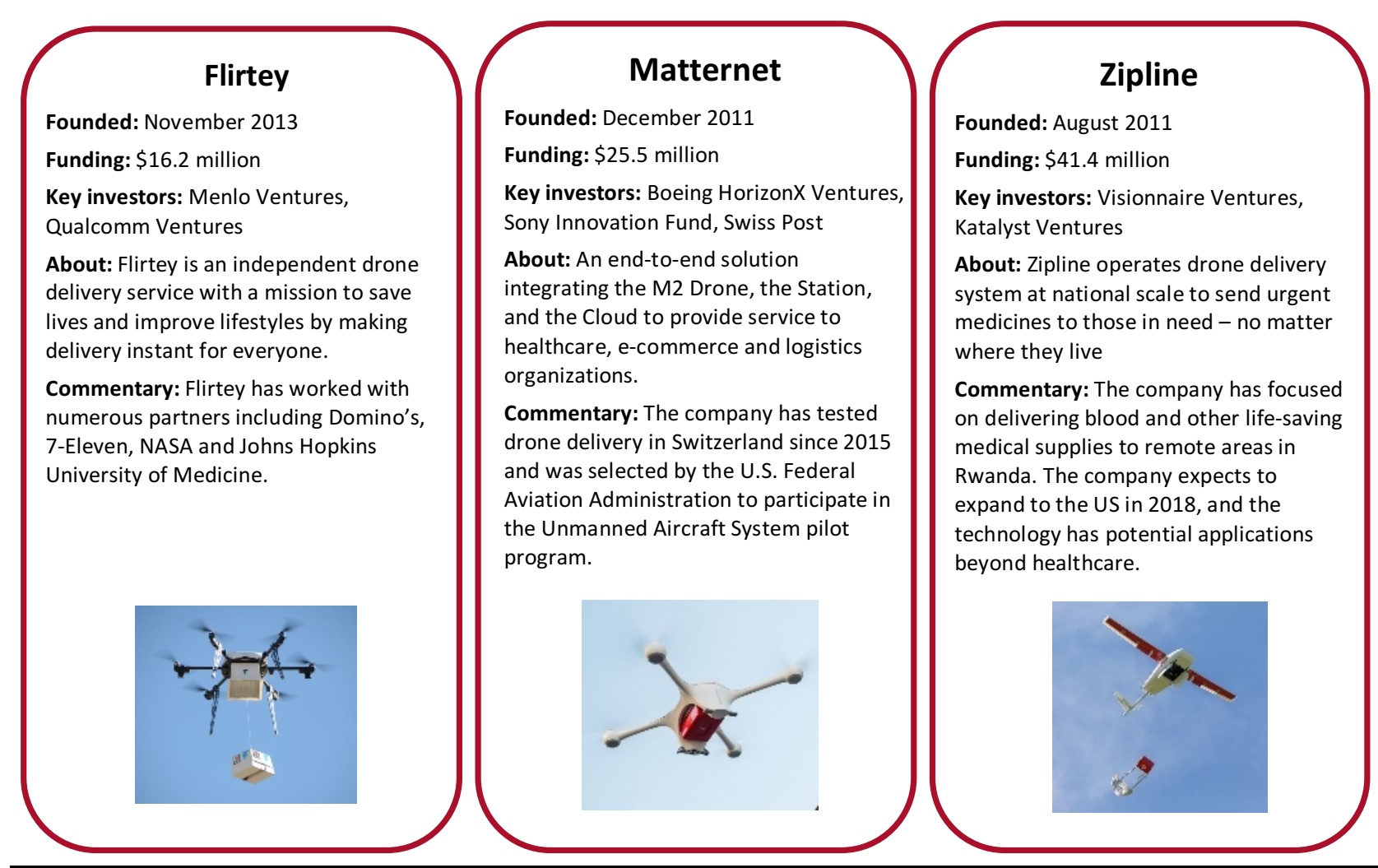

Drone Technology

Startups

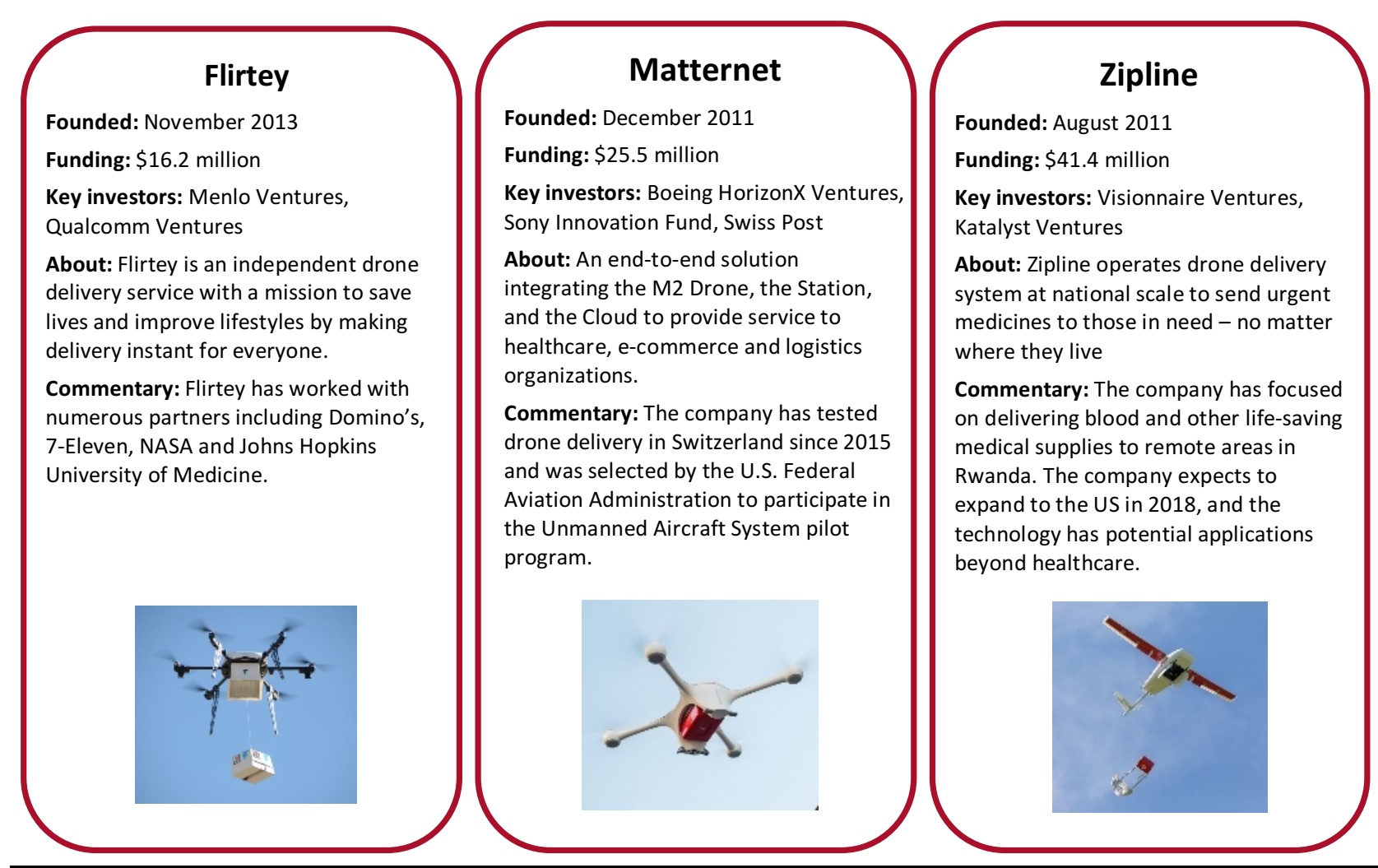

Several startups are paving the way for drone delivery technology, envisioning a future in which thousands of bots zip about the sky.

Source: Company reports, Crunchbase

Major Retailers and Logistics Providers

In addition, major retailers and logistics providers are investing in drone technology.

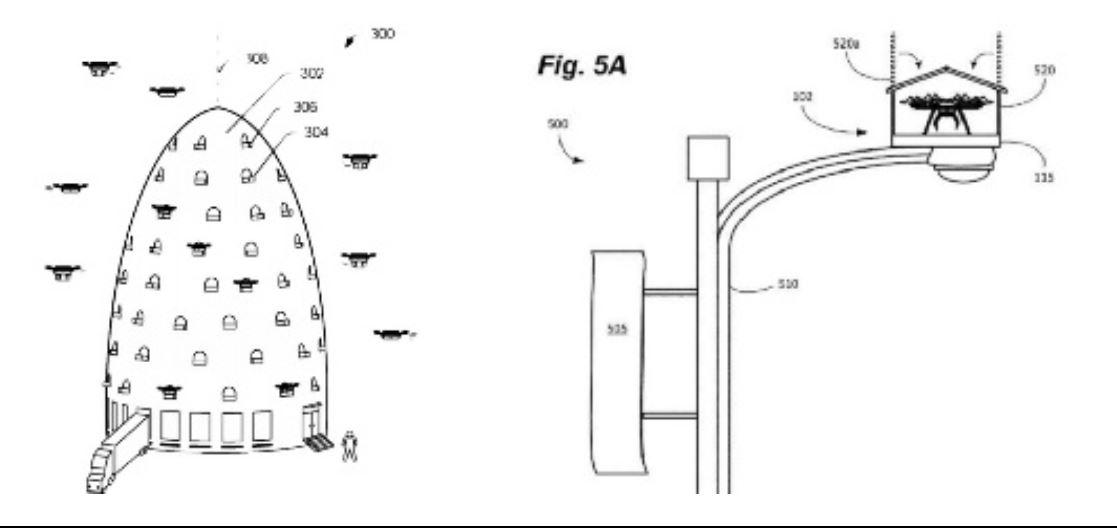

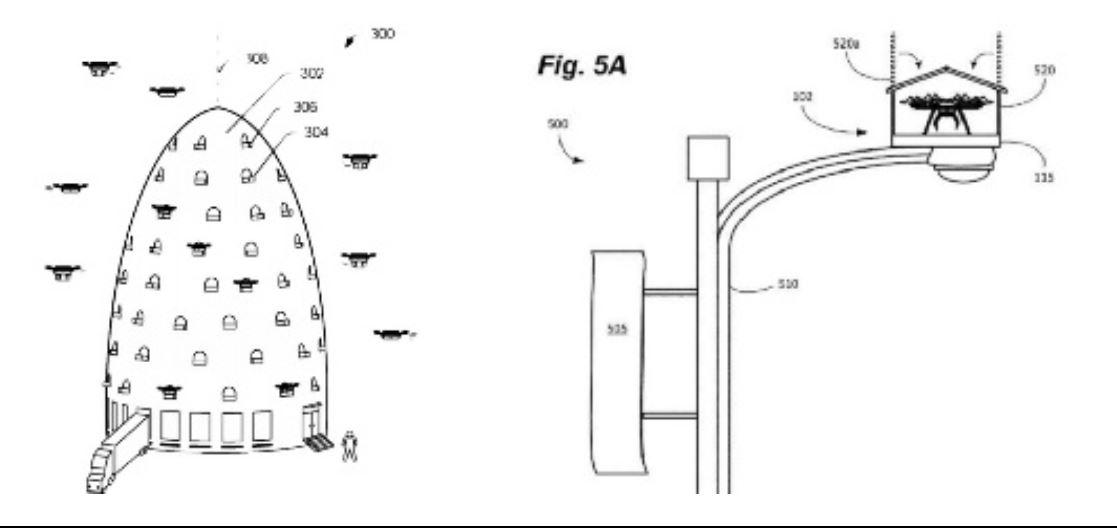

Amazon Prime Air aims to deliver packages up to five pounds in under 30 minutes. The company is conducting trials in the UK and is working with regulators to expand its tests elsewhere. Amazon has secured patents for numerous drone-related technologies, including a beehive docking tower, a street light docking system, parachute delivery mechanisms, self-destruction capabilities for malfunctioning drones and anti-hijacking features.

Source: Amazon patent filings

JD.com operates an innovation lab in China called JDX, which focuses largely on last-mile logistics technology, including drones. The drone initiative targets rural China, which, according to the World Bank, accounted for 42% of the country’s population as of 2017, equivalent to approximately 580 million people.

These consumers are spending increasingly on e-commerce, but are hard to reach via traditional delivery methods due to tricky terrain, a lack of infrastructure and distance between properties. The company aims to cut costs and grow revenues by reaching new customers.

The Economist reports that Liu Qiangdong, CEO of JD.com, expects drone delivery to cut costs by 70% once operating at scale. As of May 2017, JD.com had a fleet of 40 drones, comprised of seven distinct models with varying capabilities. The drones can carry weights up to 30 kilograms (~66 pounds), cover distances up to 100 kilometers (~62 miles) per charge and fly at speeds of up to 100 kilometers per hour. The drones fly along set routes to designated drop-off points in rural villages. The packages are then collected by village promoters who manage local delivery. As of June 2018, the company had reportedly completed 20,000 drone deliveries.

Source: JD.com

Alibaba is also testing drones, largely through its Ele.me food delivery service. In Shanghai, the company has flown meals by drone to centralized points, from which drivers retrieve and deliver the items to end users. The company also recently completed its first delivery by drone helicopter, produced by BGAC Jiangxi Helicopter Co. Ltd. The helicopter is designed to fly faster, over longer distances, carrying heavier loads than multirotor models, and aims to enable same-day delivery in areas with rough terrain.

UPS has tested drone delivery from the roof of a delivery truck. The company does not have a timeline for expanding the initiative, but imagines the technology may supplement drivers in rural areas where delivery destinations are spread out.

SF Express, one of the largest couriers in China, recently received approval from the Civil Aviation Administration (CAAC) to fly delivery drones.

Google parent company

Alphabet is taking a macro approach to drone technology through Project Wing, run through its innovation arm, X. The program seeks to enable a high volume of drones from different operators to share the skies and navigate safely. Project Wing is working with the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) in the US to develop the low altitude authorization and notification capabilities (LAANC) and with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) in Australia.

Global Advances

Drone innovation is under way globally, with research and applications spanning from Silicon Valley to Rwanda. In the US, business leaders have set high expectations for drone technology, but delays in implementation have left some skeptical of its potential or at least its timeline. China appears to be leading the pack, overcoming regulatory hurdles to begin widespread commercial testing of drone technology.

Regulatory Considerations

Despite impressive innovation, this new technology comes with tremendous logistical and regulatory challenges, particularly in the case of drones. Drones are regulated in the US by the FAA, in Europe by the European Aviation Safety Administration (EASA), in the UK by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), in Australia by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) in China by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) and in India by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), among other governing bodies.

According to a report by RAND, drone regulation in the US, China and much of Europe is generally categorized as “experimental beyond visual line of site (BVLOS).” As a baseline rule, drones must stay within a pilot’s line of site, preventing widespread implementation of the technology for package delivery. However, regulators have approved certain experimental trials, allowing delivery drones to be tested beyond the visual line of site. It is these exceptions that have allowed drone makers to test delivery capabilities.

Although delivery trials have been approved and will likely continue to take place, these limited experiments do not test some of the most significant complexities involved in a fully scaled drone delivery operation—most notably air traffic control and potential interference or hijacking. Drones face additional complexities and limitations including weather, landing locations, power capacity and charging and weight capacity.

While the technology of individual drones may advance rapidly, the notion of a retailer like Amazon coordinating 100 million Prime Day deliveries by drone, while navigating buildings, airplanes and other unmanned aerial vehicles, remains a far stretch of the imagination.

Delivery Innovation

Once a parcel arrives at its destination—whether by automobile, drone, or robot—it must be delivered securely. Last-100-feet is a significant component of last-mile logistics, presenting ample opportunity for resources to be lost or conserved. Providers may struggle to find entrances, wait for residents to answer doorbells, or make multiple delivery attempts for packages that require signature. Furthermore, packages left unguarded may be stolen, leading to additional costs and upset customers. As with transportation, significant innovation is occurring to target delivery, including smart locks and secure lockers.

Smart Locks

In their pursuit of smart lock innovation, big players such as Amazon and Google are generally not aiming to reinvent the lock itself. Rather, these companies have built smart systems and devices, and have partnered with established lock makers to integrate the components.

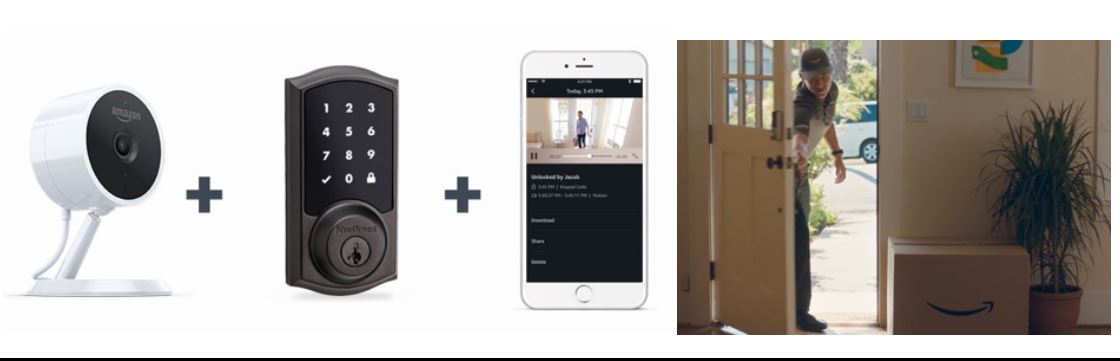

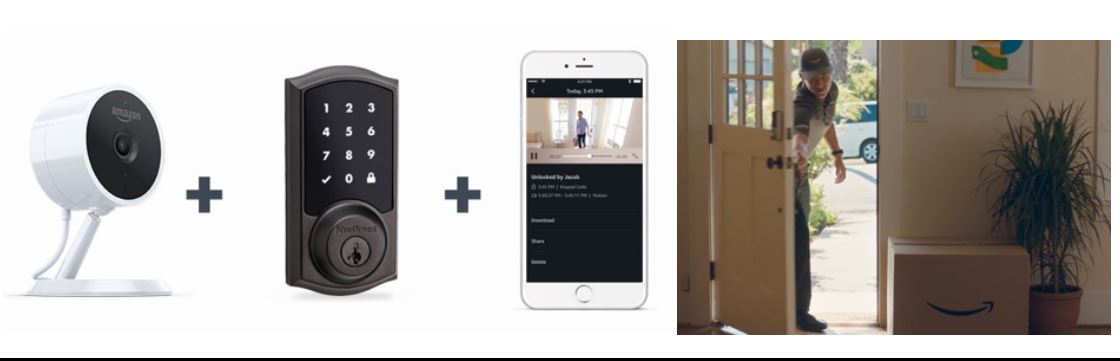

Amazon has enabled secure in-home delivery through Amazon Key. The system requires two devices—an indoor security camera called the Amazon Smart Cam and a compatible smart lock such as Kwikset or Yale, together retailing for about $250. The service is available to Amazon Prime members in eligible areas, and allows packages to be left inside the home via keyless entry. Users select the in-home delivery option at checkout and can watch a live or recorded video of the package drop-off.

In April 2018, Amazon completed the acquisition of

Ring, furthering its capabilities in smart home technology and opening new opportunities for secure delivery. Ring makes security devices including the popular Ring Video Doorbell, which is compatible with smart locks and enables users to see and speak with anyone at the door via smartphone.

Amazon’s focus on smart home technology and secure in-home delivery is not merely a solution, but rather may be seen as a strategy for the retailer to gain further share of customer’s wallets and routines. By providing a secure delivery solution compatible only with Amazon purchases, the company incentivizes customers to subscribe to Amazon Prime and buy more on its platform. Additionally, the technology gives Amazon literal entry into the home economy, where it might provide everything from automatic toilet paper replacement, to cleaning services, to security.

Source: Amazon

In early 2018,

August Home announced a similar program called August Access. The smart lock maker was founded in 2012 and raised $73 million before it was acquired by lock manufacturer Assa Abloy in 2017. August Access operates through a partnership with delivery service provider Deliv, detailed earlier. Customers whose homes are equipped with August smart locks may select in-home delivery when completing online checkout with retailers that use Deliv for distribution. August then generates a unique passcode that allows the Deliv employee to unlock the customer’s door. Like Amazon Key, August Access offers live or recorded video to users for security purposes. The service is compatible with smart locks by Emtek and Yale, also Assa Abloy brands. August Access offers a compelling solution for customers who want to maintain flexibility in their purchasing decisions, rather than buying exclusively from Amazon. With over 4,000 retail partners through Deliv according to Tech Crunch, August Access offers significant choice to customers wanting to make purchases from multiple sellers.

Google acquired

Nest in 2014, signaling its move into the start home space. Nest has partnered with Yale locks to produce a smart lock that connects with Nest systems, allowing users to grant keyless access through the company’s app. Unlike Amazon Key and August Access, however, Nest is not clearly positioned for in-home delivery as it is not partnered with a retail platform.

Smart lock technology and secure in-home delivery does not appear to be a current focus for major retailers in China.

Startups

In addition to plays by established retailers, technology companies, delivery services, and lock manufacturers, startups continue to target the smart lock segment.

Latch, a startup founded in 2014 that has raised $26 million in funding, aims to provide keyless entry in apartment buildings, serving residents, building managers and visitors. The company has a partnership with UPS to facilitate package delivery.

Lockitron, made by Apigy, which raised money through crowdfunding, faced some setbacks in production but now provides a smart lock and system for keyless entry. The company’s technology has applications to last-mile logistics but is not currently positioned as a retail delivery solution.

Consumer Sentiment

As with drones and robots, the future of smart delivery depends on consumer sentiment. Although secure in-home delivery offers potential solutions to problems including porch theft and temperature control for fresh food, the technology comes with its own set of issues. In early 2018, InsuranceQuotes published research regarding in-home delivery and trust, conducted using a survey of over 1,000 Americans. Research showed that 68.8% of participants would not be willing to use Amazon in-home delivery service.

The top five concerns related to in-home delivery were: 1) theft; 2) privacy breach; 3) malicious exploitation of Amazon’s Key; 4) personal property damage; and 5) malicious use of home data.

Outside of this survey, consumers have also expressed concerns about pets escaping and hackers tampering with locks to break into homes. In addition, some concerns about surrendering intimate access to an already-powerful player like Amazon. However, in a world where ride-hailing apps quickly turned hitchhiking-like behavior into common practice and people frequently host strangers in their homes, consumer sentiment has proven transformable.

Secure Lockers

The other leading delivery innovation is locker technology. Beyond providing secure delivery solutions, lockers may ease last-mile logistics by aggregating deliveries in centralized locations.

Amazon launched

Amazon Lockers in 2011, with lockers now available in over 2,000 spaces in more than 50 cities across the US. Located in shopping centers, gas stations, apartment buildings and offices, the self-service kiosks allow customers to pick up items at their convenience. Customers can add Amazon Lockers to their address book and ship to the locations. Packages may be retrieved within three business days of delivery using a unique code.

In 2017, the retailer launched

Amazon Hub, a locker system of similar design, but which accepts packages from all retailers. The company has partnered with brick-and-mortar businesses and apartment buildings to ensure convenient locations of its lockers and to allow for supervision. While the fee model is unclear, businesses and apartments may provide the space for free. Businesses benefit from increased foot traffic driven by the locker, and apartment complexes benefit from convenient solutions for their residents and decreased labor requirements to manage package delivery. From Amazon’s perspective, lockers improve last-mile logistics by allowing multiple packages to be delivered to a single location, eliminating failed delivery attempts and decreasing theft.

Following its August 2017 acquisition of Whole Foods, Amazon began installing lockers at the grocery store locations, at once allowing for increased convenience and driving traffic to Whole Foods locations. In March 2018, Reuters reported that 76 of the 473 Whole Foods stores had lockers.

On the logistics side, UPS Access Point, FedEx Ship&Get and DHL Packstation offer similar solutions.

UPS has partnered with small businesses to create network of neighborhood delivery points. Businesses can accept UPS packages on behalf of nearby customers, either through in-person service or unstaffed lockers. Customers can send packages directly to the access point, or have UPS attempt home delivery first before rerouting failed deliveries to the access point. The program is intended to benefit three parties—online retailers by allowing them to provide convenient delivery, customers by ensuring easy package pickup and host locations by drawing traffic to their locations.

FedEx also provides secure delivery lockers.

DHL maintains nearly 3,000 Packstation lockers in Germany using a comparable model.

Companies focused purely on lockers are also innovating in the space.

Luxer One and

Package Concierge offer secure lockers in residential, office, retail, university and mail center locations. The systems can be installed in different sizes and configurations, inside or outside, to meet the facility’s customized needs. In addition to lockers with individual compartments, setups may include package rooms. These rooms require unique codes, but are accessible to multiple residents or employees, making them somewhat less secure. They also allow for overflow at busy times and can accommodate large packages.

Luxer One and Package Concierge solutions constitute an investment by the property manager. While lockers managed by Amazon or UPS help drive sales for the providers, independent lockers in apartments or offices are monetizable only by providing clear returns to the property manager. The potential benefits are threefold:

- Secure lockers and package rooms ease the burden on property staff in managing and protecting vast delivery quantities.

- The systems may be positioned as an amenity to residents or employees whose expectations are rising and who enjoy the convenience.

- The systems provide valuable data including delivery history, package volume, and package management efficiency.

These lockers may also be positioned outside retail locations for quick or afterhours pickup.

Source: Luxor One, Package Concierge

In China,

Alibaba’s Cainiao has taken a different approach to secure lockers, designing a prototype for an individual delivery locker to be installed outside an apartment or house. The company published a lighthearted video showing the product in action. The clip features a young man ordering food on his way out for a run, receiving a delivery alert while out on the trail, and arriving home to a piping hot pizza, safe inside the locker. The Cainiao Smart Locker sits several inches from the wall, but can expand to accommodate larger packages, and the box’s temperature can be controlled remotely to adapt to food deliveries. The concept has only been tested as a prototype, but Cainiao may pursue related patents, modifications and larger-scale production.

Cainiao Box Smart Locker

Source: Cainiao

Consumer concerns regarding locker technology are more limited than with smart locks. However, some worry about the provider, especially a powerful retailer like Amazon, collecting data on their purchasing habits. With a solution like Amazon Hub, the retailer may be able to collect purchasing records even when goods are bought from third parties, and tailor its own promotions and advertising to exploit the customer.

Reverse Logistics

While transportation and delivery are the most obvious elements of last-mile logistics, the real last mile is often a backtrack, as consumers return billions of dollars of purchases. A 2017 report by Appriss Retail, drawing on data from the National Retail Federation (NRF), gives scale to the return economy. Approximately 10% of retail industry sales are returned annually in the US, equating to $351 billion worth of sales. This percentage is thought to be roughly three times higher for online purchases, particularly in categories such as apparel that require specific fit. Beyond clear cost implications, reverse logistics capabilities also impact competitive positioning and topline revenue by factoring heavily into purchasing decisions.

According to a 2017 report by Narvar, 49% of survey respondents reported checking the return policy before making a purchase online. Of the respondents, 84% reported that a “restocking fee” would prevent them from making a purchase, while 74% reported the same of “return shipping fees.”

Put simply, return policies significantly impact online sales. This also presents opportunity however, as retails can use return policies to win market share and loyalty. According to Narvar, 72% of respondents said a “no questions asked” policy would make them more likely to buy from a retailer, and 95% who were satisfied with a returns process said they would purchase with the retailer again.

Confronting costs and opportunity, retailers and startups are innovating in the reverse logistics space, both by developing systems to ease returns and through technology and incentives to minimize returns altogether.

Return Hubs

The most obvious return hub for online purchases is a corresponding brick-and-mortar location. Onmichannel retailers typically accept in-store returns of online purchases, offering a mutually-beneficial arrangement. According to the Narvar report, 38% of survey respondents prefer returning online purchases at physical stores. This preference is also to the retailer’s advantage, both as it reduces reverse logistics shipping costs and as it attracts high-intent customers who are likely to make exchanges or additional purchases in-store.

Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods represents an example of return synergies. Amazon customers can conveniently return online purchases to Whole Foods stores, while the food store can attract customers who are likely to pick up groceries or make impulse purchases.

E-commerce retailers that do not maintain physical stores can provide similar solutions by partnering with third-party return hubs. This strategy also works to supplement retailers with limited store locations, or that aim to serve an audience beyond their brick-and-mortar footprint. Many of the secure locker solutions discussed earlier also serve as drop-off points for returns. Customers can deposit return packages in locker compartments for retrieval by logistics providers. This two-way solution is both convenient and simple, consolidating inbound and outbound shipping into one system.

One downside of return lockers versus in-store returns, however, is that customers must still package the item themselves. Although goods can often be returned in their original packaging and retailers may ship items with pre-printed return labels, correctly assembling the various items requires effort that can be a hurdle to execution.

Happy Returns is startup that serves at this intersection, accepting in-person returns from multiple retailers while eliminating the need for packaging and labeling, and offering on-the-spot refunds. Like the locker providers, Happy Returns works with location partners to set up return counters inside existing establishments, offering the benefit of added foot traffic. This is foot traffic of proven spenders, and ones who have just received money back from their returns. Happy Returns collects and aggregates packages, returning them to retailers through bulk shipping when possible. Retailers can include the Happy Returns logo on their website to promote the easy solution to prospective buyers. Happy Returns was founded in 2015 and has raised $14 million in funding from investors including Upfront Ventures.

Source: Happy Returns

Return Prevention

Even better than solutions that ease reverse logistics are solutions that reduce returns altogether. Some retailers have designed programs to limit returns, and multiple companies are developing technology systems that predict likely returns, allowing retailers to tailor their strategies accordingly.

Size & Fit Technology

One of the biggest reasons for returns, particularly of online purchases, is fit. Advances in sizing tools can help reduce the burden of reverse logistics by limiting returns. A shoe retailer, for example, integrates a sizing feature at checkout. The feature allows the customer to input the size and model of his current shoe and translates the information to recommend a size for the model being purchased, even if manufactured by a different brand.

Startup

Zipfit Denim was founded to target perfect fit. The jeans retailer performs 15-minute in-person fittings and logs a detailed sizing profile for each customer to ensure proper fit with future purchases. While the solution aims primarily to eliminate the unpleasant experience of trying on jeans, it works further to limit reverse logistics costs.

Incentives

Retailers are also designing return policies to discourage returns or incentivize non-returns.

Jet.com, which was acquired by Walmart in 2016, has experimented with return rules. The seller has offered discounts on purchases if the customer agrees upfront not to return the item, or to pay a flat fee plus a cost percentage if they choose to return the item. This model is effectively like opting out of return insurance, and works by allowing the customer to place their own value on free returns. However, these tactics must be approached cautiously as the promise of free returns is a major driver or online purchases.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Companies are also using AI to predict likely returns, allowing retailers to tailor incentives for particular customers and items.

SupplyAI, a 2016 startup, offers a technology called Aspen that assists with returns management. Among other solutions, the tool allows retailers to enhance upselling during in-store returns by providing sales associates with intelligence about the customer.

Other AI companies offer tools that predict when a return is likely, either because of the item or the customer, giving retailers the opportunity to tailor promotions to the specific transaction. For example, if an item is likely to be returned, the seller may remove the item from a sales promotion or offer a deeper discount for forfeiting a free return. Given that some customers are far more likely to return items than others, this segmentation strategy can be effective for reducing the reverse logistics burden while maintaining the draw of free shipping for those who value it.

Return Incorporation

On the flip side, some retailers are actually embracing reverse logistics as a core value proposition and element of their business models.

Warby Parker was an early adopter of the two-way model. The direct-to-consumer glasses company sends shoppers five pairs of glasses for in-home try-on, expecting the samples to be returned. When a customer selects glasses for purchase, Warby Parker sends back a fresh pair.

Stitch Fix, a clothing box company, also expects high-volume returns as part of its model, allowing users to try on five carefully selected items at home and return what is unwanted. However, its taste and fit surveys, advanced algorithms and personal styling service all combat returns.

Perhaps the best example of a company that embraces returns is

Rent the Runway, founded on the premise that customers rent clothing temporarily that can be swapped out easily for different items.

When return costs are assumed and predictable, they can be more easily passed through to customers. Further, this allows for a different mentality toward return logistics, which can be regarded as a solution instead of a problem.

The Next Wave

The innovations discussed in this report are here now, whether live on the streets or in active development as prototypes and trials. Not only are robots and drones a potential widespread reality of the near future, the next, next wave of last-mile innovation is already coming into view.

Amazon has patented an underwater warehouse and a flying warehouse. Real estate developers and city planners are exploring tunnel and shaft systems to autonomously deliver goods from warehouses to individual apartments. Programmers are experimenting with predictive analytics to anticipate and ship orders before they are even placed. The possibilities for last-mile improvements are endless.

Implications

What does all of this innovation mean for the commerce economy?

For retailers, it means major investment is required to limit costs, meet consumer demands and generally remain competitive as the market evolves.

For consumers, it means more convenience, as packages can be delivered securely inside homes and returns can be made in minutes. It also means more choice about how to have purchases delivered, and about the value prescribed to convenience, for which the customer pays directly or indirectly.

For cities and neighborhoods, it means the skies and sidewalks may be congested with drones and robots, and

for regulators, a puzzle.

For local businesses, property managers and flexible workers, it means opportunities to partner with last-mile providers to ease constraints.

For all, it means goodbye to the status quo.

Last-mile logistics is a particularly costly segment of the supply chain, as aggregation synergies are dissolved and each package is routed to a separate destination. In addition to cost considerations, trends in e-commerce are driving massive delivery volumes.

According to 2016 data by Honeywell and published by BI Intelligence, last mile accounted for 53% of delivery costs, surpassing line haul, sorting and collection. And, according to data compiled by Kleiner Perkins for its Internet Trends report, the big three US delivery companies—USPS, UPS and FedEx—delivered nearly 11 billion packages in 2017, compared with fewer than 8 billion packages in 2012, suggesting a growth rate of approximately 38% over the five-year period.

Costs and volumes are perhaps the biggest issues, but numerous challenges underpin last-mile logistics including theft, repeat delivery attempts, inclement weather, rough terrain, distance between properties, consumer sentiment, regulatory restrictions, trained labor and irregular demand. While these challenges complicate last-mile logistics, they also present exciting opportunities for innovation at every step.

Last-mile logistics is a particularly costly segment of the supply chain, as aggregation synergies are dissolved and each package is routed to a separate destination. In addition to cost considerations, trends in e-commerce are driving massive delivery volumes.

According to 2016 data by Honeywell and published by BI Intelligence, last mile accounted for 53% of delivery costs, surpassing line haul, sorting and collection. And, according to data compiled by Kleiner Perkins for its Internet Trends report, the big three US delivery companies—USPS, UPS and FedEx—delivered nearly 11 billion packages in 2017, compared with fewer than 8 billion packages in 2012, suggesting a growth rate of approximately 38% over the five-year period.

Costs and volumes are perhaps the biggest issues, but numerous challenges underpin last-mile logistics including theft, repeat delivery attempts, inclement weather, rough terrain, distance between properties, consumer sentiment, regulatory restrictions, trained labor and irregular demand. While these challenges complicate last-mile logistics, they also present exciting opportunities for innovation at every step.