Executive Summary

As e-commerce in China becomes increasingly crowded, brands and retailers are looking for alternative ways to connect with their end customers. In response, CBEC platforms such as Tmall Global and Netease Kaola have been experimenting with setting up offline retail stores in China. This means that foreign retailers and brands will now be able to sell directly to Chinese consumers without having to go through the lengthy import and distribution processes that accompany traditional trade channels. Despite this, there are still several key obstacles:e-commerce platforms and retailers alike must ensure that all of the products pass customs clearance regulations and procedures, while still providing a positive customer experience.

An Introduction to Offline CBEC Stores

The emergence of CBEC has enabled Chinese consumers to purchase foreign products in China with greater ease than ever before. The new import model cuts through the red tape and lengthy procedures required for overseas retailers to register a China entity and apply for an import permit, making it easier for them to sell directly to Chinese consumers.

Consumers now have a legitimate avenue through which to purchase products directly from overseas retailers at affordable prices, whereas in the past, they have had to purchase through friends or family based overseas, or through individual

daigou, agents who act as middlemen purchasing products overseas on behalf of Chinese consumers and profiting off the price difference.

Despite this, the recent opening of brick-and-mortar stores by Tmall Global and Netease Kaola in Hangzhou show that branching into offline retail is inevitable for pure-play e-commerce players, both retailers and marketplaces alike. The reasons are clear—as e-commerce user growth slows as the market matures, traffic acquisition and online marketing operations become increasingly expensive. There is only a limited amount of time that Internet users can spend online in a given day, and retailers have to spend more and more money to get a piece of that time.

International e-commerce players are moving to offline retail in China to reach consumers who have yet to begin purchasing overseas products or who are looking for more convenience or a way to trial the goods before they commit to buying them. In today’s competitive market, brands are also looking for a physical space in which they can build a stronger connection with their target customers.

What Is Holding Back the Offline Retail Expansion of CBEC?

The issue with taking CBEC offline lies within the very nature of the regulations that dictate how it works—all products imported via CBEC are regarded by China customs authorities as personal goods, and as such,authentication of the consumer’s identity is required. In other words, there needs to be an actual consumer to pay for the products as well as authenticate the order with their personal ID card, transaction records, logistics information and payment serial number when the product is imported.

Because of all the paperwork and information needed to process an order, it is difficult for retailers to completely fill a brick-and-mortar store with CBEC goods that they can sell to consumers in a hassle-free transaction. It is much easier if the products are imported via general trade, as the authorities do not have to worry about illegal transactions going through untaxed, and consumers do not have to submit so much information to the government authorities.

However, e-commerce companies and retailers alike have been lobbying for offline CBEC stores for quite some time. Demand for overseas products has risen considerably and retailers are seeking ways to reach Chinese consumers without having to deal with the middleman—the importers and distributors.

In the next section, we discuss the evolution of the offline retail stores over the past few years, as well as their pain points and how they continue to evolve. We also highlight a few leading examples of the offline stores that players such as Tmall Global, Netease Kaola and Little Red Book have set up.

The Evolution of Offline CBEC

In the preceding section, we introduced offline CBEC and discussed some of the challenges key players face in setting up offline retail stores, particularly with regards to custom clearance issues. Next, we dig a bit deeper and explain how offline CBEC retail stores have evolved over the past few years.

Offline CBEC Stores v1.0—O2O Experience Stores

The first brick-and-mortar stores for CBEC appeared in 2015 and were known as O2O experience stores. Consumers could visit these stores, where they could view and touch the products, but could not buy them on the spot. These early-stage CBEC O2O experience stores did not have products displayed in a ‘bonded’ status; the products that were on display in-store were either used products, or empty shells/packaging collected from users.

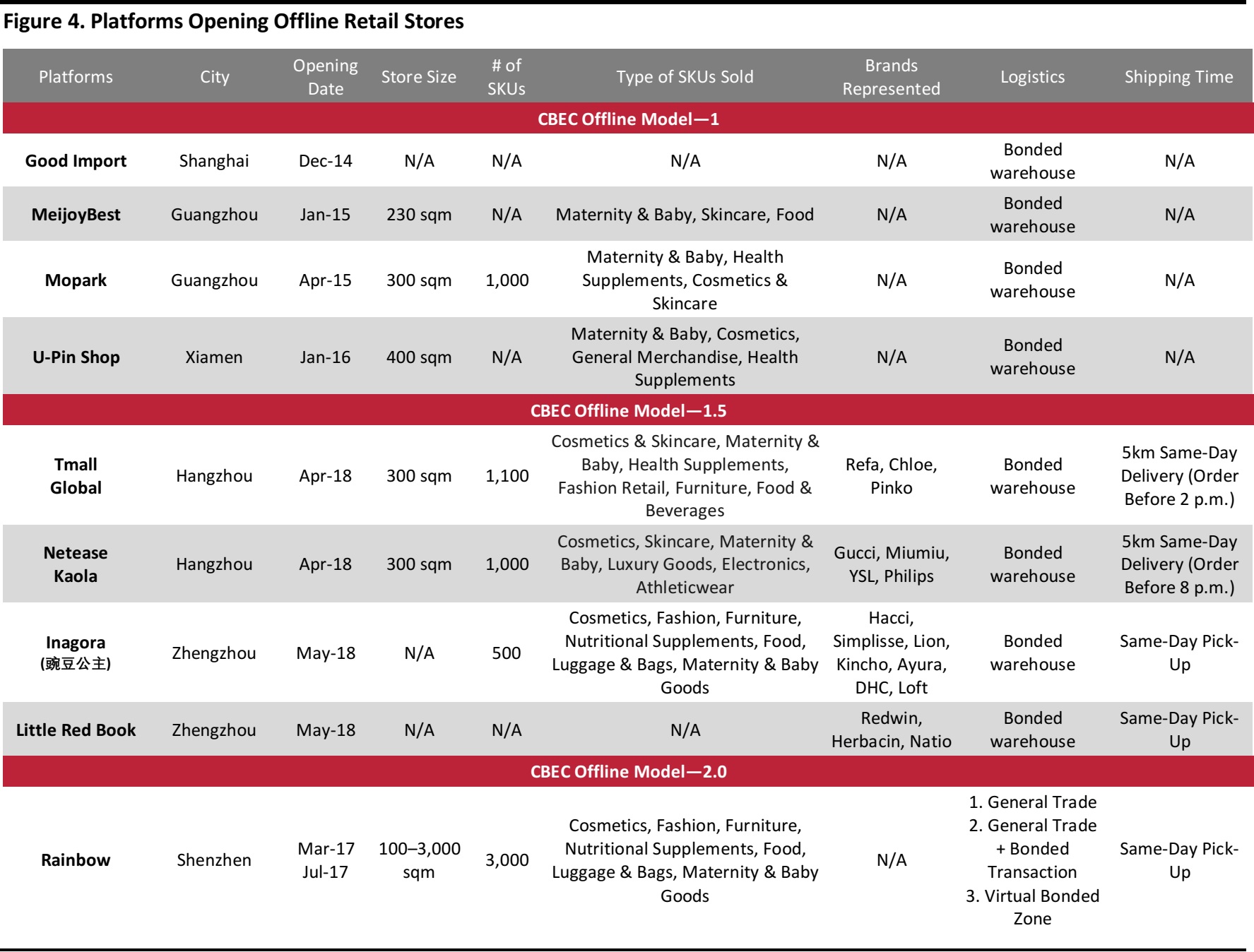

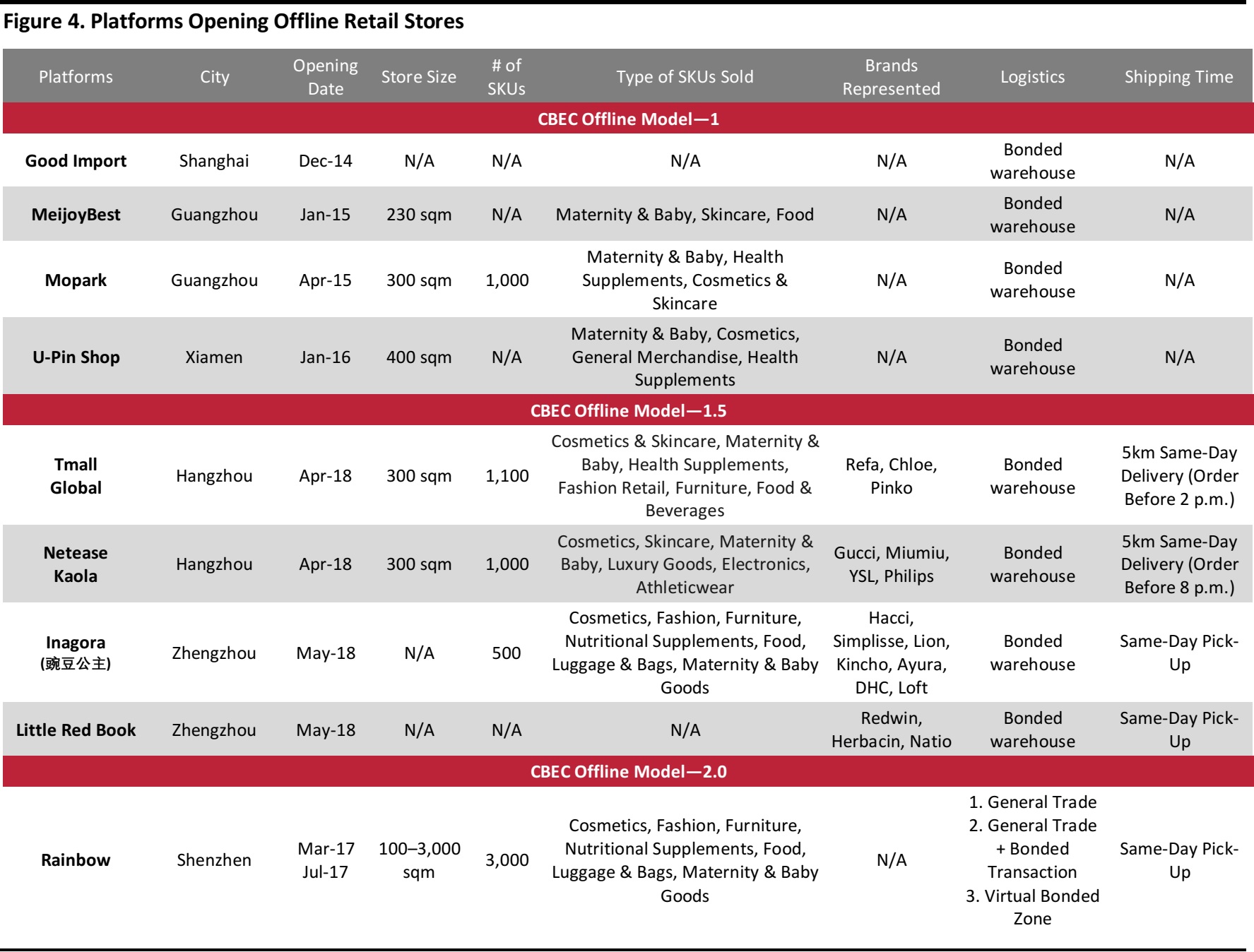

Examples include the MeijoyBest store (opened in January 2015) and the Mopark store (April 2015) in Guangzhou, U-Pin Shop in Xiamen (January 2016) and the Good Import store in Shanghai’s free-trade zone (December 2014). Customers would scan a QR code to order the products they wanted, which were then stored in bonded warehouses. The goods would then be imported and taxed according to general trade regulations, so in essence, they were not really CBEC goods. They would then be delivered to the customers’ home.

The customer experience for these first offline retail stores was less than ideal: 1) seeing and testing products on the shelf that were not available for purchase on the spot was frustrating for many customers; 2) many of the shelves were stocked with empty packages; 3) the selection of products was also highly limited; and 4) many of these stores were inconveniently located in logistics zones, far away from the city center in logistics zones.

Offline CBEC Stores v1.5—“The Stores Look Much Better, but You Still Cannot Take the Products Home with You”

The next version of the offline brick-and-mortar CBEC store was one where consumers could view the products and goods in person, but would still have to order through the online CBEC platforms, with the goods shipped to their homes at a later date.

The benefit of this second version of the CBEC store was lower import duties, as the goods would be taxed as CBEC goods rather than as general trade goods. However, consumers could still not take the goods home with them. The reason being that with bonded transactions, consumers need to submit the order, payment and logistics information to China Customs and the China Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, as well as pay the corresponding import duties.

Because of the amount of documentation that must be submitted for the relevant authorities to approve a transaction, doing everything online makes things that much easier. The vast majority of CBEC stores employ this method. Two such examples are Tmall Global and Netease Kaola, which set up stores in downtown Hangzhou in April 2018, each with 1,000 or so SKUs across cosmetics, fashion, maternity & baby, furniture, and food & beverages. They both offer same-day delivery for consumers living within a 5-kilometer radius of store locations.

Source: Sohu News

Source: Sohu News

Source: Kaola Weibo Page

Source: Kaola Weibo Page

In May of this year, two new offline retail stores opened in Zhongdamen, the e-commerce zone of Zhengzhou city, operated by Little Red Book and Inagora, a CBEC company that specializes in importing Japanese goods. The goods are stored nearby in Zhengzhou’s Henan Bonded Logistics Center and go through a shortened custom clearance process before being picked up by the consumer. Inagora boasts 500 SKUs from leading Japanese brands, and Little Red Book reportedly offers a simplified three-minute checkout process.

Source: Sina News

Source: Sina News

While the Zhongdamen trial VFTZ may provide a convenient shopping experience for customers wanting to do CBEC shopping, there are still some obstacles: 1) the mall itself is located in a distant suburb of Zhengzhou, a 90-minute drive from the city center; 2) it is also not clear how long it takes for customers to pick up their goods, even though the bonded logistics center is conveniently located.

Offline CBEC Stores v2.0—CBEC + New Retail

In the latest version of the offline CBEC store, consumers can view, purchase and take home the latest imported goods on the spot. The most well-known examples is Rainbow, a large department-store chain, which set up a test store in Shenzhen in March 2017, and later set up an enormous 3,000-square-meter store in July 2017. This store is located next to Shenzhen’s well-known Coastal City shopping complex and carries a whopping 3,000 SKUs. With a special certificate issued by the Shenzhen customs authorities, this store sells goods in three different ways: 1) general trade, in which the import duties have already been paid; 2) general trade + bonded transaction, whereby the goods are sold first and the duty is paid later by the customer; and 3) cross-border bonded transactions, whereby consumers have to submit the relevant information and pay the CBEC duties.

In the first two cases, consumers can pay on the spot and take home the imported goods they have purchased. The products stocked in the Rainbow store are either bonded products or duty-paid products.

In the third scenario, customers must wait for their goods to be cleared from the bonded zone warehouses before they can be picked up at the store or delivered directly to their home address.

Below, we provide a recap of some of the platforms that have opened up offline retail stores.

Source: Azoya

Source: Azoya

Why International Retailers Should Care

There will always be demand from consumers who shop predominantly offline. For retailers that want to expand offline, the CBEC-model-powered VFTZ could be a potential route to sell offline.

However, the VFTZ model is still in the testing phase, and currently, there are not many cross-border retail stores in major commercial areas to satisfy consumer demand for more convenient access. In the near future, brick-and-mortar practices will need to focus more on improving logistics and O2O services for Chinese

haitao shoppers, which would allow consumers to order goods online and pick them up offline.

The majority of products that can be accepted in the customs-regulated VFTZ still require a commercial license and registration certificate from the CFDA, which serves as a barrier for international brands and retailers.

For retailers and brands, the core function of the VFTZ is to provide a physical space to showcase their products and provide an offline experience for customers. While the v2.0 VFTZ model is still far from perfect, it may still be a viable option for brands that are considering branching into offline retail.

Source: Sohu News

Source: Sohu News Source: Kaola Weibo Page

Source: Kaola Weibo Page Source: Sina News

Source: Sina News Source: Azoya

Source: Azoya