Nitheesh NH

On December 26, 2018, the Indian government unexpectedly announced a revised FDI policy for e-commerce. Since 2010, when it first allowed 100% foreign investment in business-to-business e-commerce, international firms such as Amazon set up intricate joint-venture and holding company structures to cleverly navigate the Indian e-commerce landscape.

As marketplaces are technically technology platforms that facilitate trade between buyers and sellers, existing e-commerce marketplaces in India raised large amounts of foreign funding as a way to allow international firms to penetrate the retail landscape in the country. The framework for FDI in e-commerce also paved the way for Amazon to establish a significant foothold in the country with its marketplace model and complex ownership structures with vendors, and so provide stiff competition to homegrown online retailers.

While several subsequent revisions to the policy for FDI in retail and e-commerce were welcome and opened opportunities for further growth of foreign entities, the latest one is rather limiting. Moreover, market leaders claim that the time given to alter their existing corporate structure is rather short and may even disrupt trading in the short term.

Earlier versions of the policy iterated that:

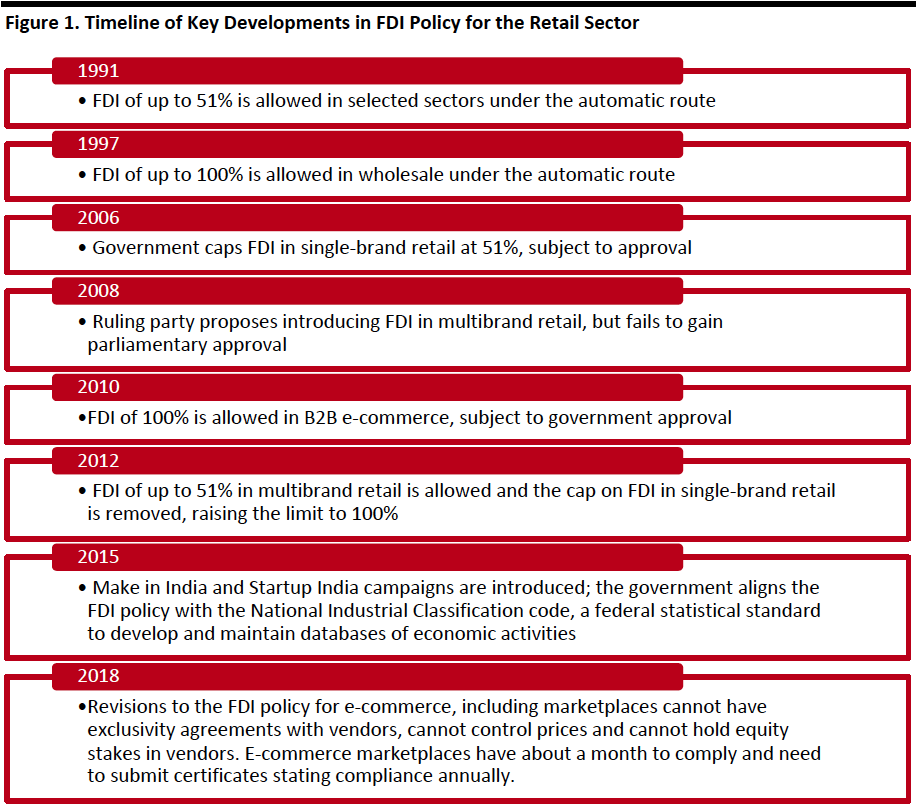

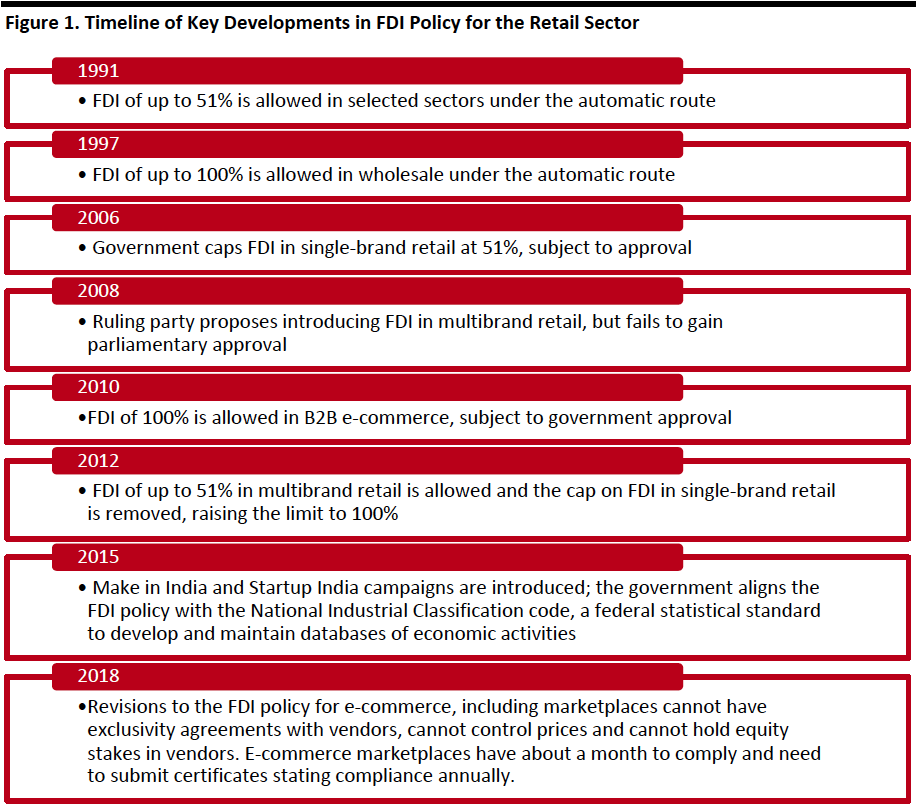

Figure 1. Timeline of Key Developments in FDI Policy for the Retail Sector[/caption]

Coresight Research View: New Rules to Have Little Impact in the Long Term

Players such as Amazon have managed to steer around the FDI rules despite the many changes over the years. We think these new rules will have a short-term impact on selling until the e-commerce marketplaces work out new contracts and re-word exclusivity agreements with existing vendors. In terms of ownership structures, international companies may need to look at innovative ways of partnering with domestic retailers to be able to sell freely online until there is a significant upheaval to the existing rules.

Figure 1. Timeline of Key Developments in FDI Policy for the Retail Sector[/caption]

Coresight Research View: New Rules to Have Little Impact in the Long Term

Players such as Amazon have managed to steer around the FDI rules despite the many changes over the years. We think these new rules will have a short-term impact on selling until the e-commerce marketplaces work out new contracts and re-word exclusivity agreements with existing vendors. In terms of ownership structures, international companies may need to look at innovative ways of partnering with domestic retailers to be able to sell freely online until there is a significant upheaval to the existing rules.

- FDI is allowed only for a marketplace model and not an inventory-based model of e-commerce.

- More than 25% of a marketplace’s revenues should not be from a single vendor or its group companies.

- A marketplace should not exercise ownership over the inventory or goods sold through the site.

- E-commerce marketplace operators “will not directly or indirectly influence the sale price of goods or services and shall maintain level playing field.”

- A vendor’s inventory will be considered as controlled by a marketplace entity if over 25% of it is purchased from the marketplace or its group companies.

- E-commerce marketplace operators cannot mandate exclusivity, i.e. they cannot ask sellers to sell particular products exclusively on their platform.

- A marketplace operator or companies in which it has equity participation can provide services, such as warehousing, logistics, fulfillment, advertisement, marketing, payments, financing and more, to vendors on the platform. But these services need to be provided “at arm’s length and in a fair and non-discriminatory manner.”

- If certain terms of services provided to vendors are made unavailable to other vendors, it will be considered discriminatory.

- An e-commerce marketplace entity will need to furnish a certificate and a report by a statutory auditor confirming compliance to all the rules laid out in the circular by September 30 each year.

Figure 1. Timeline of Key Developments in FDI Policy for the Retail Sector[/caption]

Coresight Research View: New Rules to Have Little Impact in the Long Term

Players such as Amazon have managed to steer around the FDI rules despite the many changes over the years. We think these new rules will have a short-term impact on selling until the e-commerce marketplaces work out new contracts and re-word exclusivity agreements with existing vendors. In terms of ownership structures, international companies may need to look at innovative ways of partnering with domestic retailers to be able to sell freely online until there is a significant upheaval to the existing rules.

Figure 1. Timeline of Key Developments in FDI Policy for the Retail Sector[/caption]

Coresight Research View: New Rules to Have Little Impact in the Long Term

Players such as Amazon have managed to steer around the FDI rules despite the many changes over the years. We think these new rules will have a short-term impact on selling until the e-commerce marketplaces work out new contracts and re-word exclusivity agreements with existing vendors. In terms of ownership structures, international companies may need to look at innovative ways of partnering with domestic retailers to be able to sell freely online until there is a significant upheaval to the existing rules.