Nitheesh NH

Introduction

The coronavirus has had a huge impact on retail globally in 2020. Consumers are now focused on their health, their families, their jobs and their finances. Many are quarantined at home, and lifestyles are changing as needs supersede wants and desires. For brands and retailers of non-essential products, the landscape has dramatically changed due to a sharp drop-off in demand and widespread store closures implemented to limit the spread of the coronavirus. Personal luxury goods are considered non-essential in the prevailing environment, and sales in the sector have fallen sharply. This report looks at the global personal luxury goods industry, including its recent performance and major players. We provide an outlook of global luxury that is severely affected by the coronavirus through 2021, and we discuss what luxury brands are doing to help fight the pandemic. In addition to exploring the luxury e-commerce market, this report looks back to the Great Recession of 2007–2009 to assess how the luxury retail sector fared and how it might compare to the current crisis. Finally, the Chinese luxury shopper is an important driver of global luxury spend, so we analyze the exposure of major luxury companies to the China market. As the nation recovers from the coronavirus, early signs of shoppers flocking to luxury retailers are encouraging, but reduced international travel by Chinese and other luxury shoppers in 2020 will limit sales of luxury goods globally.Key Insights

With only essential retailers open for business in much of the developed world (Europe, the US and parts of Asia) as this report is published, the coronavirus has proved to be the most pivotal driver for discretionary purchases in 2020 so far. Throughout most of the world, luxury shops are closed for business due to the impacts of the pandemic. However, the coronavirus has nearly run its course in China, where the outbreak originated, and the nation is now seeing signs of a renewed consumer interest in luxury—with queues outside Shanghai flagship stores, for example. The luxury industry has achieved a 4.8% CAGR since 2000, largely benefiting from the popularity of luxury goods among Chinese consumers. That said, a return to the status quo is not likely to occur this year or next. As this report is published, we are in the eye of the storm and anticipate weakened demand for luxury products through 2020, with any recovery postponed until late in 2021 at the earliest and a return to 2019’s levels unlikely to be seen until 2022. Even following the end of the crisis, whenever that may be, we expect consumer behaviors to be changed in the long term: Depending on the depth of economic damage, many of 2019’s luxury shoppers may not have the inclination or the finances to go on a spending spree. One of the most vibrant luxury trends over the past decade has been the growing influence of street culture, which has attracted a new generation of luxury shoppers and at the same time lowered price points. This has enabled a wider audience to participate in luxury—in effect, representing the democratization of luxury. We expect some of these more recent luxury shoppers to drop out of the market due to the coronavirus, demonstrating the adverse economic impact of the pandemic. Heritage brands are vestiges of value that luxury shoppers trust amidst uncertainty, which bodes well for brands such as Chanel, Christian Dior, Louis Vuitton and Ralph Lauren. Modern luxury brands that mix heritage with inclusivity and accessible price points—Coach, for example—are well positioned for the current environment. We sense the pendulum swinging from ostentatious to demure, from over the top to minimalist. Not only has the coronavirus caused demand destruction, it brought with it supply disruption. Many manufacturing regions have shut down amid the pandemic, impacting the luxury supply chain. To help fight the pandemic, a number of luxury brands have diverted factory operations to manufacture personal protective equipment (PPE), a move that will endear them globally and build brand equity in the long term. Luxury shoppers in China have propelled growth in the luxury sector for the past 20 years and will remain a key driver of the market based on their number and economic motivation. However, near-term demand for luxury products is being adversely impacted by the global economy, and early signs of a luxury recovery in China will not be enough to offset the industry’s remaining 65% of sales elsewhere in the world that are in severe decline due to the pandemic. That said, it is encouraging to see those lines in front of the Chanel flagship in Shanghai. Luxury has been criticized for being late to e-commerce, although motivations to keep shopping experiences offline for effective brand management are justified. However, the coronavirus crisis has made it very clear how important a digital strategy is for consumer-facing businesses and brands. Luxury brands that do not have a robust digital strategy—spanning opportunities for brand discovery, customer engagement, commerce, marketing and storytelling—will be left behind this decade.A Brief Look at 2019

A number of trends marked the luxury sector 2019: increased consumer interest in brands with purpose; growing acceptance of luxury rental; consignment and resale models by consumers and brands alike; the continued dominance of big brands—most notably Chanel, Christian Dior, Gucci and Louis Vuitton; and turnarounds, repositionings and new creative designers gaining traction, such as the recent strength of Saint Laurent and Bottega Veneta. One of luxury’s leading creative forces for more than 60 years passed away in February last year. Karl Lagerfeld joined Chanel in 1983, where he renewed the brand’s cultural relevance by taking brand codes (chains, pearls and tweed) and adapting them to a new consumer, redefining luxury at the same time. Lagerfeld’s list of firsts includes the first luxury-sport collaboration in the form of the Chanel X Reebok designer sneaker FURY (2001, before the rise of Virgil Abloh, a designer who specializes in luxury streetwear and sportswear) and the first collaboration between a designer brand and high street retailer (H&M in 2004). During 2019, we lost Barneys, a New York City-based modern luxury department/specialty store. The retailer was once a destination to discover cutting-edge, avant-garde fashion along with perennial favorites such as Dries Nina Ricci, but it faced increasing competition from online luxury players and rental and resale choices, as well as the challenge of high fixed costs. The brick-and-mortar business model became obsolete for Barneys, and the retailer saw reduced footfall (store traffic). The intellectual property was purchased by Authentic Brands Group and licensed to Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) to create “Barneys at Saks” at the Saks Fifth Avenue department store. The Barneys Madison Avenue location was closed. HBC initiated a move to go private in 2019, which was completed in early 2020. This has allowed the oldest department store in North America to navigate a repositioning without the added pressure of public shareholders. The company has been unwinding assets as part of its global acquisition strategy over the past 10 years. HBC still owns Hudson’s Bay department stores, Saks Fifth Avenue and Saks Off Fifth. Rental and resale captured consumer attention in 2019 and remains a key trend to watch this year, as younger generation become more environmentally conscious. Luxury consignment platform The RealReal went public in May 2019 and recorded full-year GMV of $1 billion, with a 40% year-over-year increase in active buyers. Rental platform Rent the Runway, which specializes in designer goods, continued to expand its business by adding children’s clothing and partnering with Nordstrom in 2019. The coronavirus pandemic has negatively impacted the rental and resale business as consumers stay at home and reduce their spending on discretionary items. In addition, although it is unclear how long the coronavirus can survive on soft surfaces, consumer perception may be that renting apparel or purchasing pre-owned fashion items could increase the risk of being exposed to the coronavirus. However, we expect that constrained budgets and potential luxury supply shortages will mean that rental and resale services could become a popular option when people are shopping again for luxury products after the pandemic.Market Landscape

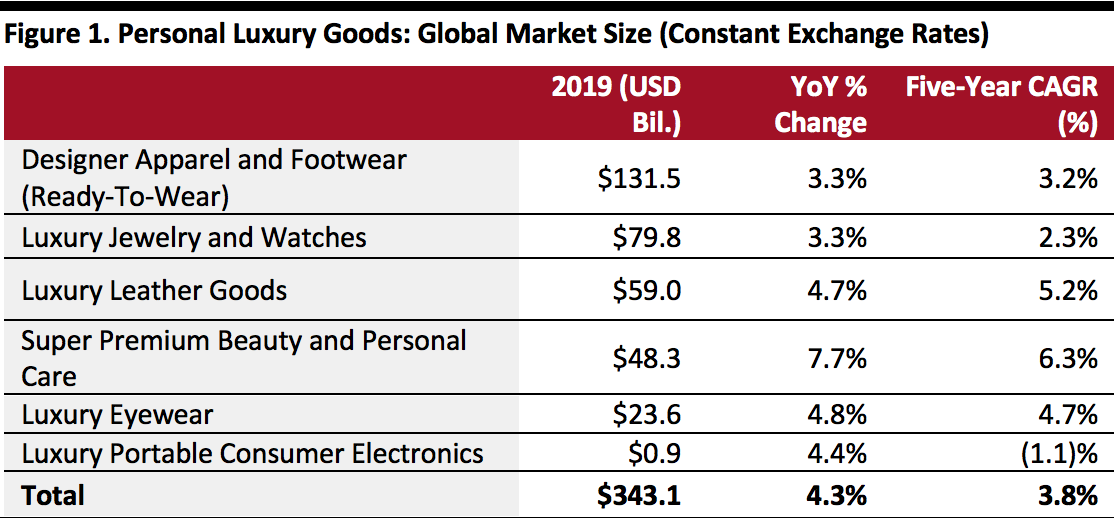

The global personal luxury goods market reached $343.1 billion in 2019, up 4.3% year over year at constant exchange rates, according to Euromonitor International. This growth was primarily driven by the luxury beauty and skincare sector, which grew 7.7% year over year in 2019, followed by luxury eyewear and luxury leather goods. The five-year CAGR for the total personal luxury goods market during the 2014–2019 period represented more moderate growth of 3.8% at constant exchange rates, led by the premium beauty and personal care sector and luxury leather goods (see Figure 1). [caption id="attachment_107815" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Source: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved[/caption]

Coresight Research estimates that the global personal luxury goods market will decline 20–25% at constant exchange rates in 2020, largely due to the widespread global impact of the coronavirus, which has already caused disruption in travel and has halted consumer discretionary spending in those regions on lockdown. When stores reopen and consumers return to a new normal, we expect that luxury products will gradually come to hold appeal once again, but this may be a slow process—2021 will likely begin weak and pick up as the year progresses.

However, we expect premium beauty and personal care to remain a significant category for sales throughout 2020, particularly in the case of small luxury items. Last year, when Gucci relaunched its makeup line, the brand sold over 1 million units of its $42–46 lipsticks within the first month. Notably, this demand for such small luxury items has continued during the coronavirus pandemic. For example, the Hermès lipstick line (comprising lipsticks priced at $67 each) sold out at Bloomingdale’s in New York City in less than 10 days from the March 4 launch. While each item may be considered expensive, owning one of these lipsticks represents inexpensive access to a premier luxury brand and is therefore a meaningful, yet not too costly, indulgence.

We are seeing today’s luxury consumer place more importance on inclusivity and cultural relevance, and we expect value-based brands to meet these demands and thus achieve sales growth. Another emerging trend is status signaling, rather than status seeking. Sustainability remains a core value for luxury brands, which is resonating with today’s shoppers, as they seek differentiation and values in the products they choose.

[caption id="attachment_107816" align="aligncenter" width="520"]

Source: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved[/caption]

Coresight Research estimates that the global personal luxury goods market will decline 20–25% at constant exchange rates in 2020, largely due to the widespread global impact of the coronavirus, which has already caused disruption in travel and has halted consumer discretionary spending in those regions on lockdown. When stores reopen and consumers return to a new normal, we expect that luxury products will gradually come to hold appeal once again, but this may be a slow process—2021 will likely begin weak and pick up as the year progresses.

However, we expect premium beauty and personal care to remain a significant category for sales throughout 2020, particularly in the case of small luxury items. Last year, when Gucci relaunched its makeup line, the brand sold over 1 million units of its $42–46 lipsticks within the first month. Notably, this demand for such small luxury items has continued during the coronavirus pandemic. For example, the Hermès lipstick line (comprising lipsticks priced at $67 each) sold out at Bloomingdale’s in New York City in less than 10 days from the March 4 launch. While each item may be considered expensive, owning one of these lipsticks represents inexpensive access to a premier luxury brand and is therefore a meaningful, yet not too costly, indulgence.

We are seeing today’s luxury consumer place more importance on inclusivity and cultural relevance, and we expect value-based brands to meet these demands and thus achieve sales growth. Another emerging trend is status signaling, rather than status seeking. Sustainability remains a core value for luxury brands, which is resonating with today’s shoppers, as they seek differentiation and values in the products they choose.

[caption id="attachment_107816" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Source: Hermès[/caption]

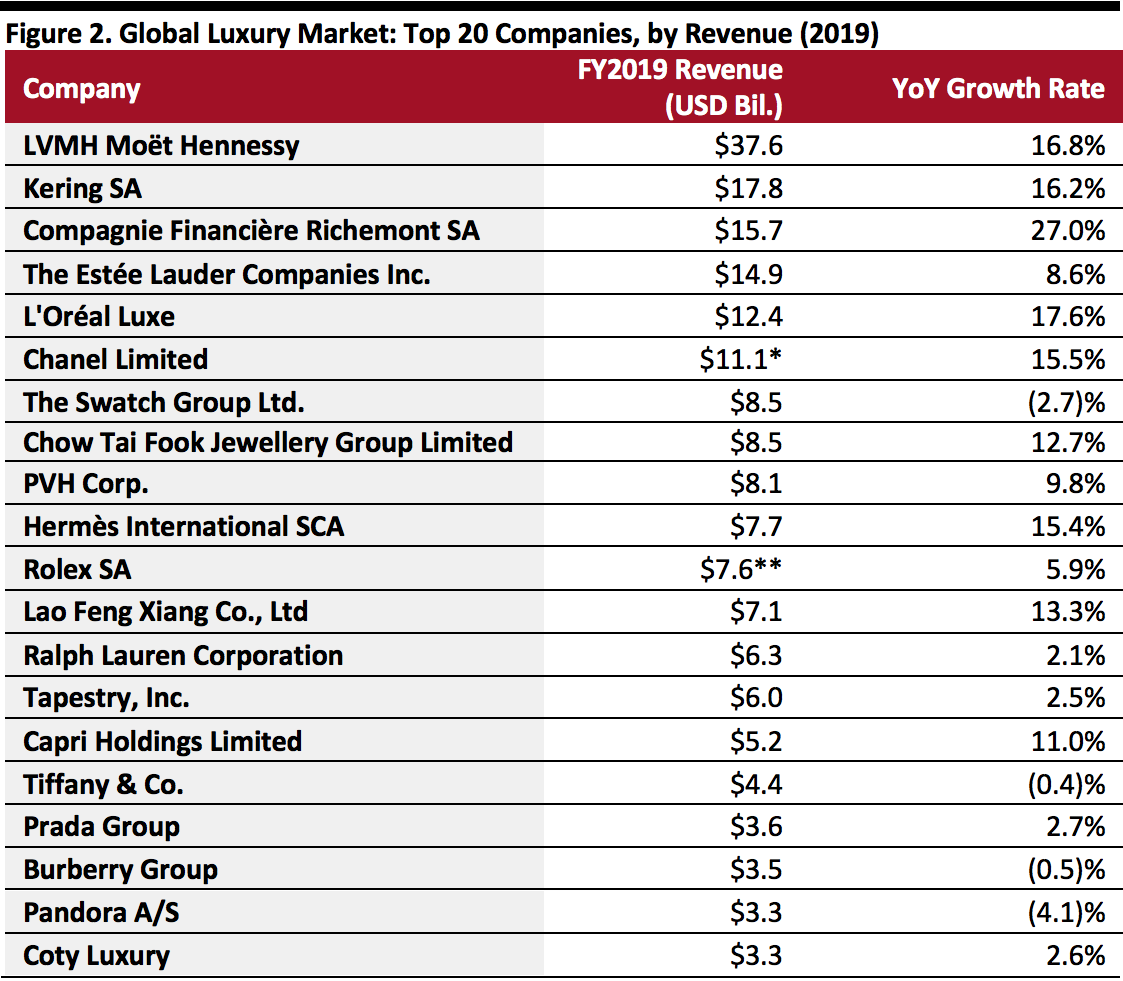

The personal luxury market is highly concentrated, with 20 companies accounting for about 60% of the total global market in 2019, in terms of sales. Of these, nine posted double-digit year-over-year sales growth (see Figure 2). Richemont grew the fastest, with revenue jumping 27% in fiscal year 2019, driven by the inclusion of YOOX Net-a-Porter (YNAP) revenues (Richemont completed the purchase of the remaining 50% of YNAP in May 2018). Aside from Richemont’s performance, L'Oréal set the pace with a 17.6% sales gain, closely followed by leading luxury portfolio companies, LVMH and Kering. Watch and jewelry companies Pandora and Swatch experienced the highest sales declines among the top 20 companies.

[caption id="attachment_107817" align="aligncenter" width="520"]

Source: Hermès[/caption]

The personal luxury market is highly concentrated, with 20 companies accounting for about 60% of the total global market in 2019, in terms of sales. Of these, nine posted double-digit year-over-year sales growth (see Figure 2). Richemont grew the fastest, with revenue jumping 27% in fiscal year 2019, driven by the inclusion of YOOX Net-a-Porter (YNAP) revenues (Richemont completed the purchase of the remaining 50% of YNAP in May 2018). Aside from Richemont’s performance, L'Oréal set the pace with a 17.6% sales gain, closely followed by leading luxury portfolio companies, LVMH and Kering. Watch and jewelry companies Pandora and Swatch experienced the highest sales declines among the top 20 companies.

[caption id="attachment_107817" align="aligncenter" width="520"] *Chanel’s 2018 total revenue; 2019 figure is not available

*Chanel’s 2018 total revenue; 2019 figure is not available**Rolex’s 2018 total revenue; 2019 figure is not available

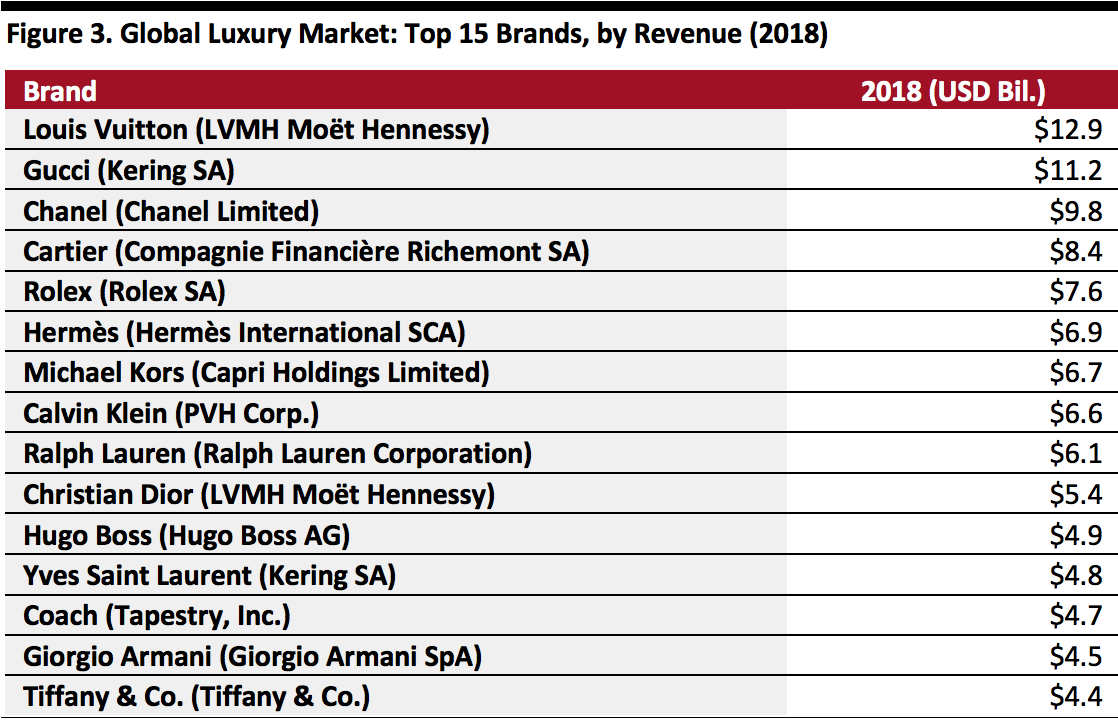

Source: Company reports/Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved[/caption] Turning to brands, the top 15 global luxury brands accounted for 32% of total personal luxury sales in 2018, according to the latest data available from Euromonitor International (see Figure 3). European luxury powerhouses LVMH and Kering dominated the market. Interestingly, only five of the top brands are from the US. [caption id="attachment_107818" align="aligncenter" width="520"]

Source: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved[/caption]

Source: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved[/caption]

Luxury E-Commerce

Luxury brands were slow to embrace e-commerce, with the fear that wider access and a less experiential selling environment would ruin exclusivity. Today, online has become the fastest-growing channel, increasing by 22% in 2019 and representing 12% of global luxury sales, according to management consulting firm Bain & Co. If luxury companies were not already operating through e-commerce, the coronavirus pandemic has acted as a call to do so—not necessarily to offer a brand’s entire range of product, just enough to appease the demand of quarantined luxury shoppers. It is quite likely that a number of luxury houses received orders over the phone too. The current situation in the US has also necessitated brands to use the digital channel to stay relevant and engage with consumers—by telling brand stories, for example—in order to secure custom in the longer term. In addition to brands’ own websites, online luxury boutiques and marketplaces are gaining popularity among consumers, as they allow shoppers to browse hundreds of styles from a wide variety of brands. These third-party online platforms are easy to navigate and offer more flexible return policies for shoppers. They have also become the preferred channel for luxury brands that lack in-house digital capabilities. Below, we discuss some of the major players in this market. Farfetch is an online luxury goods marketplace that features over 3,400 brands. The company’s annual revenue in fiscal year 2019 grew 69% year over year to $1 billion. The retailer acquired online sneaker platform Stadium Goods in December 2018 and New Guards Group in August 2019. Luxury conglomerate LVMH launched its e-commerce site 24 Sèvres (24S) in 2017, which offers more than 150 brands—including 20 of the company’s own. LVMH has not provided separate financial information for 24S, but the platform’s sales come from international shoppers across 100 countries, of which the US is a key customer base. Lyst hosts thousands of online fashion stores, bringing 5 million products from 12,000 of the world’s leading brands and retailers into one marketplace. The company’s annual revenue was $23.7 million in fiscal year 2019, increasing by 20% year over year. MatchesFashion.com, a UK-based online platform, is home to over 450 designers, and offers editorials and reports on fashion and design. MatchesFfashion reported a 27% surge in annual sales to $488.5 million in fiscal year 2019, ended January 2019. The retailer also operates three physical stores in London. Moda Operandi is a luxury website carrying over 1,000 brands and featuring established and emerging international designers. The company extended into offline retail by opening a store in New York, and it now has a global network of physical showrooms and personal stylists. Mytheresa.com is an international online retailer that features 250 popular fashion brands. Acquired by Neiman Marcus Group in 2014, the retailer reported year-over-year sales growth of 24% to $421.1 million for fiscal year 2019, ended January 2019. Secoo is the largest online luxury retailer in China, providing upscale products and services from 3,800 domestic and global brands. Secoo has established collaborations with 143 brands, including Prada, Stella McCartney, Thom Browne and Valentino. The company most recently reported a sales increase of 24% to $271.6 million in the third quarter of 2019, ended September 30. The RealReal is the largest online site for consigned luxury goods, and the company operates four brick-and-mortar stores in US. Its sales jumped 49% from 2018 to 2019, reaching $318 million, while GMV grew 42% year over year. Tmall Luxury Pavilion was launched in 2017 by Alibaba as a dedicated platform for China’s high-end consumers. The site hosts over 150 luxury brands, with products ranging from fashion and beauty items to luxury cars. As of February 2020, millennials are the platform’s core customer base, accounting for 45% of total sales. YOOX Net-a-Porter Group (YNAP), which is owned by luxury conglomerate Richemont, is an online luxury and fashion retailer that serves customers in more than 180 countries. Richemont reported sales of $2.05 billion between April and December 2019 through its online distributors, which include YNAP and Watchfinder & Co. Net-a-Porter suspended operations in Europe, the Middle East and the US on March 27, 2020, due to the coronavirus situation.2020: The Coronavirus and Its Impact

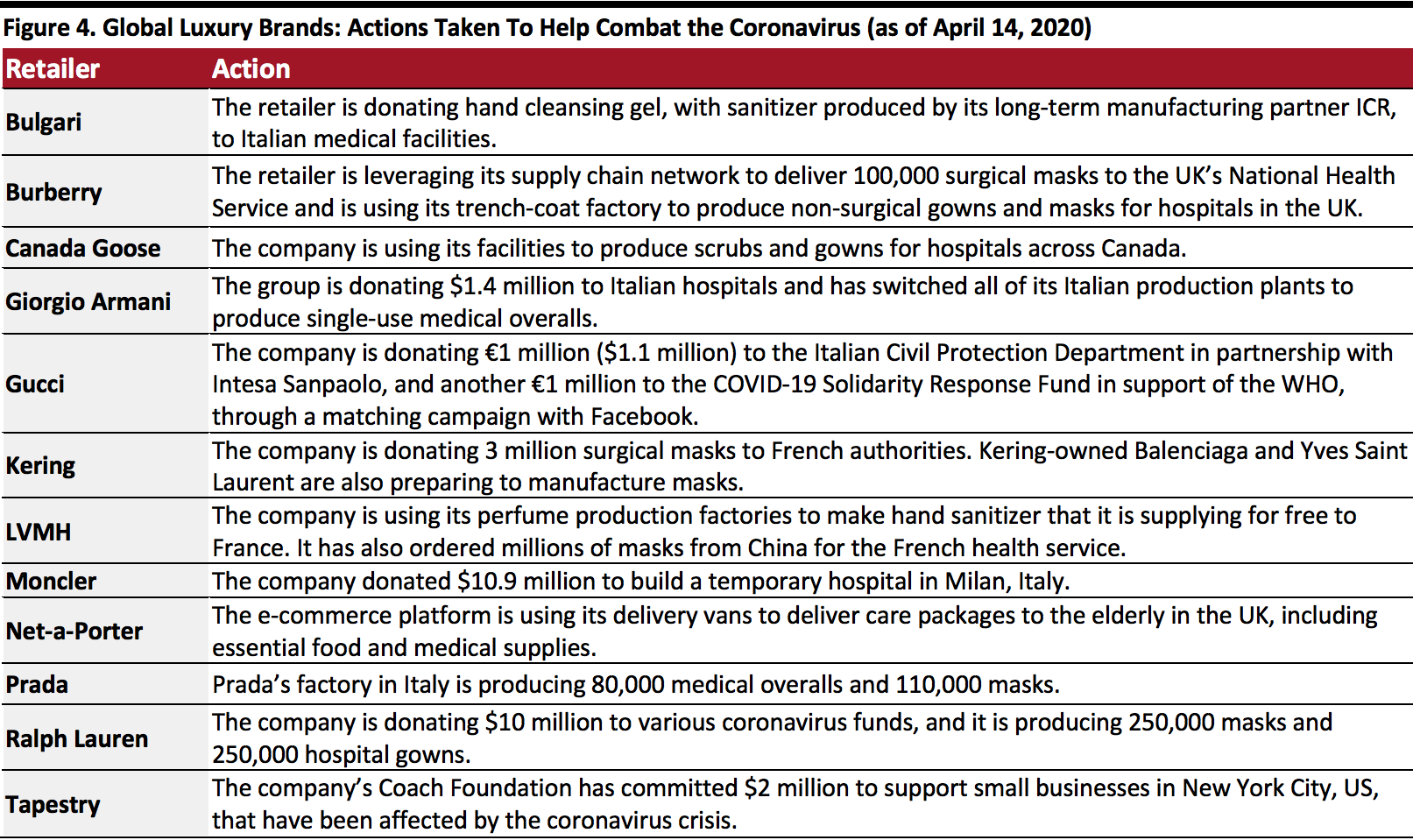

The coronavirus has proved highly disruptive to the luxury industry. In terms of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, people around the world are currently primarily concerned with physiological needs and safety—considering their own health, the health of their family and friends and the broader community and society as they know it. This brings issues of mortality to the front and center, as consumers prioritize essential purchases to survive the coronavirus crisis. Of course, luxury items do not fall under these priorities. We saw early examples of hoarding and price gouging on some items, but by and large this has since dissipated. Now, people are thinking of the economic impact of the coronavirus, including lost wages and reduced wealth—not an ideal backdrop to drive purchases in the luxury sector. In this environment, Coresight Research has advised clients to engage and communicate with consumers in order to deepen long-term relationships: Sales are inevitably going to suffer in the near term, so ongoing communication with consumers will be key for the future recovery of the luxury sector. The good news is that we are seeing Shanghai returning to some level of normalcy, and shoppers are queueing up to enter luxury flagships. The release of some pent-up luxury demand is a positive, though perhaps unsurprising, sign—but an adverse impact of the coronavirus may be a loss of aspirational shoppers, which will pressure luxury growth in 2020 and likely into 2021. In the US, unemployment claims are skyrocketing, with more than 10 million filed in the final two weeks of March. Recent estimates indicate that as many as 30–35 million people are currently unemployed due to the coronavirus crisis. European unemployment will likely swell as well. Unemployment obviously heavily affects the disposable income of consumers, which points to reduced demand for luxury products in 2020–2021. An equally important factor is consumers’ propensity to shop, employed or otherwise. This is sign of sentiment, confidence and emotional state, which we believe will be restored gradually once the coronavirus pandemic is over, resulting in a U-shaped sales trend for global luxury goods, rather than a V-shape return to growth. The weakened macroeconomic backdrop, along with consumer uncertainty spanning employment, income, health and wealth, will reduce the number of aspirational shoppers that luxury brands are able to attract in the near to medium-term future. International travel is virtually at a standstill due to the coronavirus, as is domestic travel. Travel and tourism are important drivers of spending in the luxury sector, and although home quarantines will come to an end at some point, we believe that people will remain reluctant to travel internationally for some time, particularly given that 14-day quarantine measures are likely to remain in place for travelers from some regions. Visits to international luxury flagship locations will be reduced. In sum, with the exclusion of the Chinese luxury shopper, most of the levers of luxury demand are on mute. Furthermore, while Chinese luxury shoppers are now returning to stores, traffic has not yet restored to year-ago levels—which were hit by the China-US trade war. The coronavirus has impacted portions of the luxury supply chain as well: With France and Italy on lockdown, many of the top global luxury brands are unable to manufacture product even if they so desired. Representing a silver lining during this situation, many of these brands have used their manufacturing facilities to produce items that contribute to the fight against the coronavirus (see Figure 4), such as hand sanitizer, masks and other PPE equipment for medical staff. Taking such action should help brands to build on their reputations and brand equity in a time when they sales are down. Following the coronavirus crisis, we believe that the supply chains in the luxury sector will recover before demand returns. [caption id="attachment_107819" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Luxury and Recession

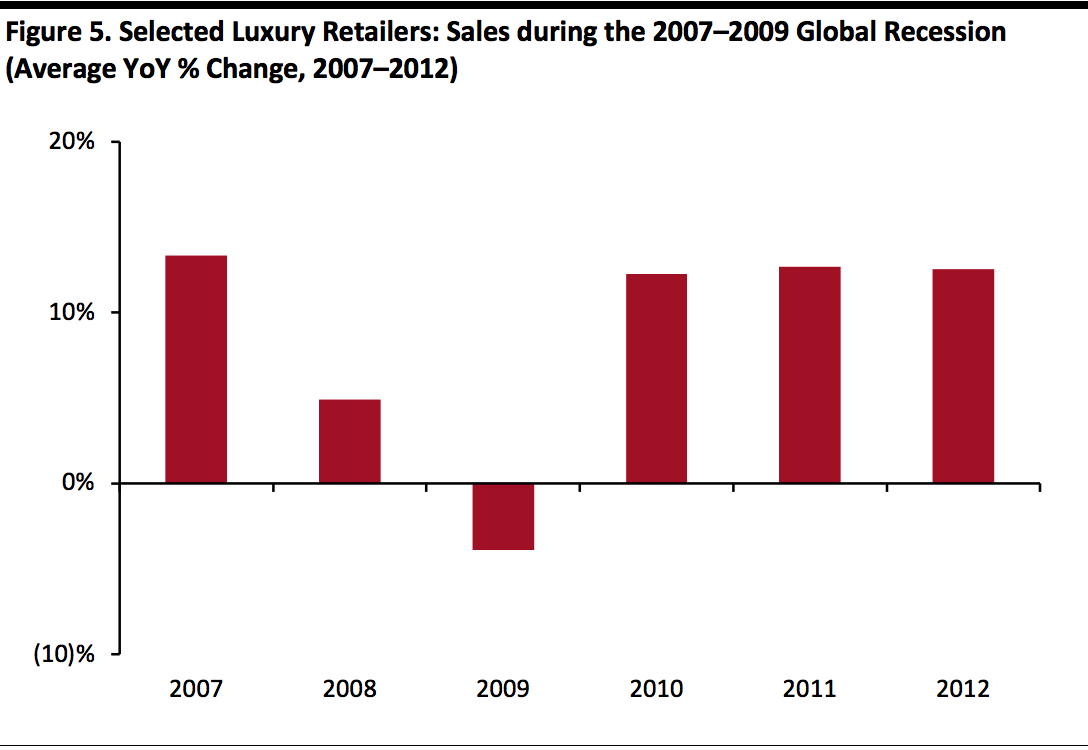

Due to the Global Recession of 2007–2009, the global personal luxury goods market shrank by 7.5% in 2009, according to data from Bain & Co. However, sales recovered rapidly in 2010, bolstered by increased luxury spending by Chinese consumers. In the US, high-end department stores took a heavy hit during the Global Recession, with average sales of both Neiman Marcus (which also owns Bergdorf Goodman) and Saks, Inc dropping 7.4% in 2008 and 14.1% in 2009. It was not until 2013 that sales at Neiman Marcus returned to pre-recession levels. Saks, Inc never topped its pre-recession sales before it was acquired by Hudson’s Bay Company in 2013. Luxury brands held up slightly better. The eight luxury companies we looked at—Burberry, Hugo Boss, Kering, LVMH, Ralph Lauren, Richemont, Tapestry and Tiffany & Co.—experienced an average sales decline of 3.9% in 2009 (see Figure 5). This number was heavily affected by a 21% dip from Kering, although Kering’s Gucci sales rose in the fourth quarter of 2009. On the other hand, luxury conglomerate LVMH saw sales fall by less than 1%, while Burberry and Tapestry each posted a sales uptick in 2009. All companies except Kering rebounded quickly in 2010 with double-digit revenue growth. [caption id="attachment_107820" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Selected retailers: Burberry, Hugo Boss, Kering, LVMH, Ralph Lauren, Richemont, Tapestry and Tiffany & Co.

Selected retailers: Burberry, Hugo Boss, Kering, LVMH, Ralph Lauren, Richemont, Tapestry and Tiffany & Co.Source: S&P Capital IQ[/caption] The coronavirus pandemic in 2020 is an exogenous event that is impacting the global economy, whereas the Global Recession of 2007–2009 was a product of the sub-prime mortgage crisis and derivative financial instruments that seriously weakened and damaged the balance sheets of many of the largest financial institutions. We expect the genesis and momentum of the Chinese luxury shopper to be a critical factor in the recovery of the coronavirus crisis, as they will be the most vibrant luxury consumer over the next 24 months. We discuss this demographic below.

China’s Luxury Shoppers

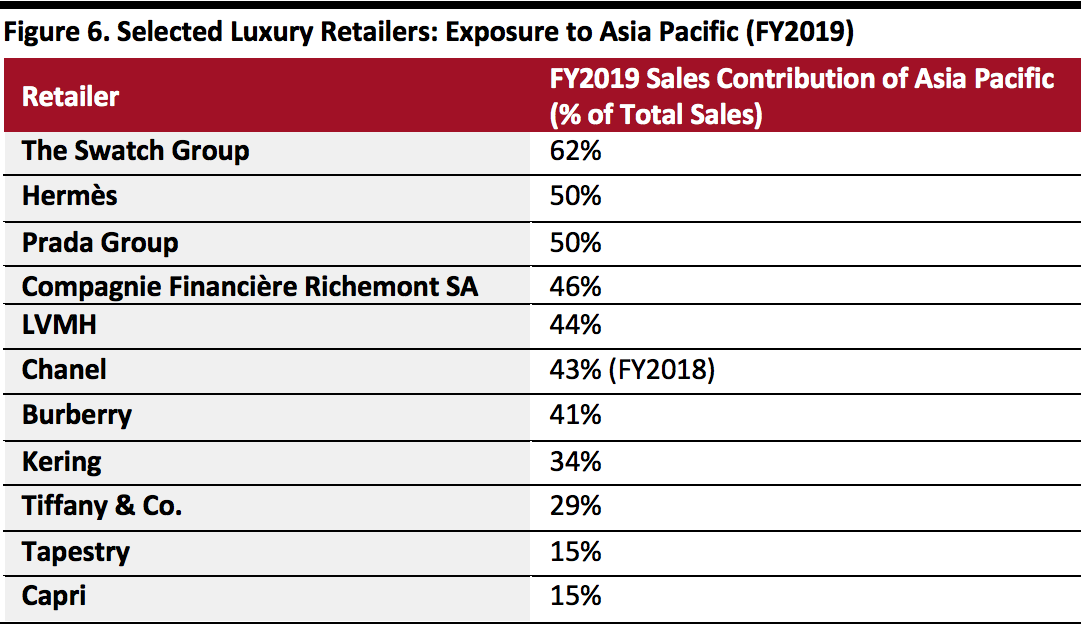

Chinese consumers have taken the lead in luxury shopping over the past decade. Back in 2000, Chinese luxury spending only accounted for a low, single-digit percentage of the whole market, but it represented 35% of global personal luxury purchases in 2019 and is expected to reach 46% by 2025, according to Bain. Chinese consumers also contributed 90% of the growth in the global personal luxury market last year. Chinese consumers are likely to limit their luxury spending this year due to the coronavirus. A recent survey by consultancy firm China Luxury Advisors found that 59% of Chinese respondents said they are more likely to reduce spending on luxury handbags and apparel in 2020. In a previous Coronavirus Insights report, we estimated that 70% of luxury spending by Chinese consumers was overseas in 2019. That number is most likely to drop in 2020, as numerous countries have imposed lockdowns and travel restrictions, and worried consumers are reluctant to travel abroad. That said, Chinese consumers may be inclined to shop domestically this year. [caption id="attachment_107821" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Source: Company reports[/caption]

Despite the negative impact of the coronavirus pandemic, we believe that Chinese consumers will continue to be the key driver of global luxury growth in the coming years, fueled by the expanding middle class and increasing spending power among younger generations. Furthermore, Chinese local governments recently issued digital vouchers and waived the value-added tax in some provinces to encourage spending. By embracing the digital channel, luxury brands should be better positioned to gain shares from other weaker players.

As China embraces signs of recovery from the pandemic, we are seeing consumers begin to return to stores. It also should be noted that by March 24, the world’s largest apparel and footwear brand, NIKE, had re-opened 80% of its stores in China—a market that accounted for 17% of the company’s total sales in 2019. NIKE has been a significant innovator in the luxury space, collaborating with Supreme (2002), Riccardo Tisci (2014, when he was creative director at Givenchy), Virgil Abloh (2017), Kim Jones (at Louis Vuitton and Dior Men) and many more designers—mixing streetwear, sports performance and authenticity with luxury heritage and design. This is a strategic mix for attracting today’s younger consumers to heritage luxury brands.

Young Chinese luxury shoppers discover products and brands digitally, follow key opinion leaders (KOLs) and compete to acquire the latest on-trend luxury product—whether that be a bag, a pair of sneakers or a lipstick. Although Chinese shoppers are the most active digitally engaged shoppers, luxury brands in particular can benefit from this demographic finding the physical shopping experience appealing, whereby consumers can feel and try on products in brick-and-mortar stores, as well as experience and engage with the brand.

[caption id="attachment_107822" align="aligncenter" width="520"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Despite the negative impact of the coronavirus pandemic, we believe that Chinese consumers will continue to be the key driver of global luxury growth in the coming years, fueled by the expanding middle class and increasing spending power among younger generations. Furthermore, Chinese local governments recently issued digital vouchers and waived the value-added tax in some provinces to encourage spending. By embracing the digital channel, luxury brands should be better positioned to gain shares from other weaker players.

As China embraces signs of recovery from the pandemic, we are seeing consumers begin to return to stores. It also should be noted that by March 24, the world’s largest apparel and footwear brand, NIKE, had re-opened 80% of its stores in China—a market that accounted for 17% of the company’s total sales in 2019. NIKE has been a significant innovator in the luxury space, collaborating with Supreme (2002), Riccardo Tisci (2014, when he was creative director at Givenchy), Virgil Abloh (2017), Kim Jones (at Louis Vuitton and Dior Men) and many more designers—mixing streetwear, sports performance and authenticity with luxury heritage and design. This is a strategic mix for attracting today’s younger consumers to heritage luxury brands.

Young Chinese luxury shoppers discover products and brands digitally, follow key opinion leaders (KOLs) and compete to acquire the latest on-trend luxury product—whether that be a bag, a pair of sneakers or a lipstick. Although Chinese shoppers are the most active digitally engaged shoppers, luxury brands in particular can benefit from this demographic finding the physical shopping experience appealing, whereby consumers can feel and try on products in brick-and-mortar stores, as well as experience and engage with the brand.

[caption id="attachment_107822" align="aligncenter" width="520"] Chinese consumers lined up outside the Chanel store in Shanghai

Chinese consumers lined up outside the Chanel store in ShanghaiSource: Coresight Research[/caption]

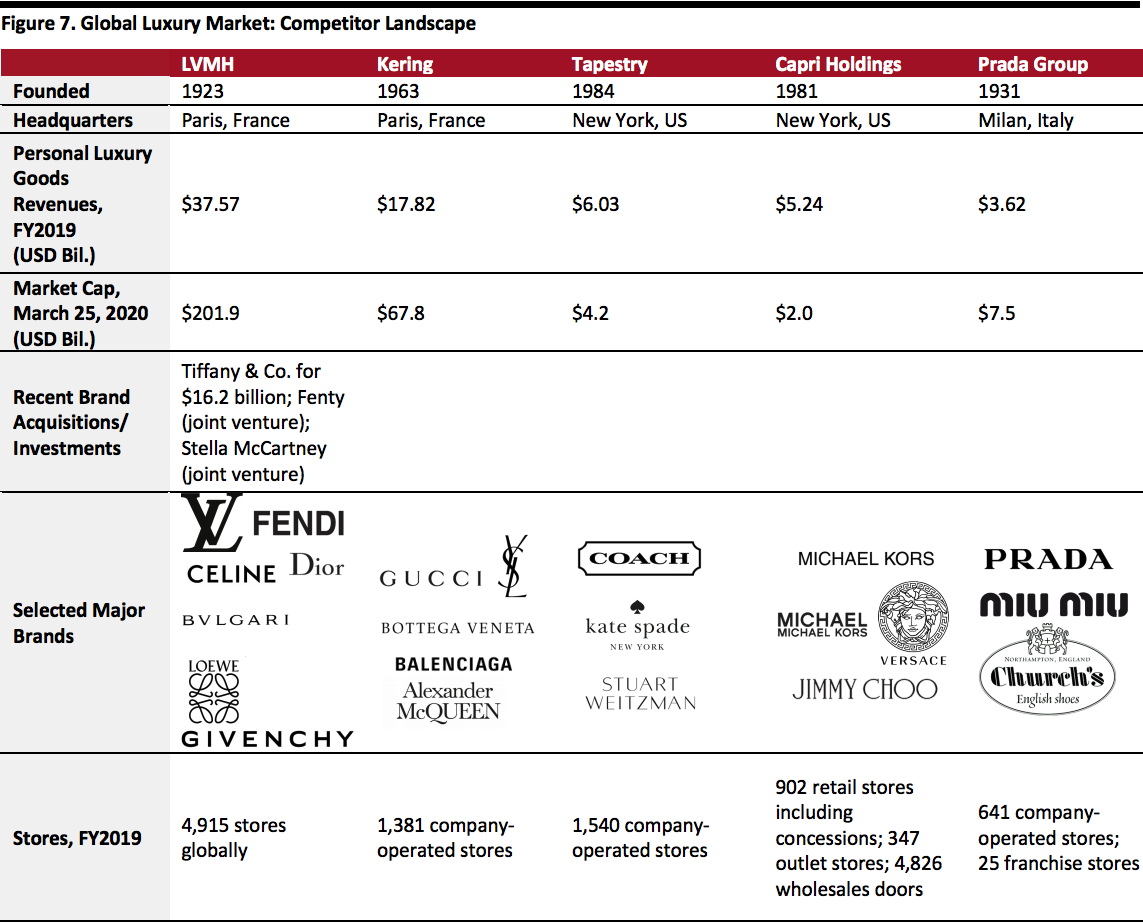

The Luxury Market’s Competitor Landscape

[caption id="attachment_107823" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Company reports/S&P Capital IQ[/caption]

Source for all Euromonitor data: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved

Source: Company reports/S&P Capital IQ[/caption]

Source for all Euromonitor data: Euromonitor International Limited 2020 © All rights reserved