Introduction

What’s the Story?

The grocery market in India is a predominantly unorganized sector (90%–95%), comprised of general stores, kirana stores (mom-and-pop stores), convenience stores, informal street markets and stalls and vegetable and fruit vendors that sell fresh produce via pushcarts. These unorganized players operate alongside organized modern grocery retail outlets that make up 5% of the sector, including supermarkets and hypermarkets that sell local produce, imported food and other products.

However, we expect the organized retail segment to grow amid evolving urban lifestyles and consumer preferences to shop at hypermarkets and supermarkets that offer a wide range of brands and products, in-store services and technologies.

In this report, we examine the push of Western grocery retailers into India’s grocery landscape, the features and opportunities of the Indian grocery sector, the barriers to entry and key players in the sector.

Why It Matters

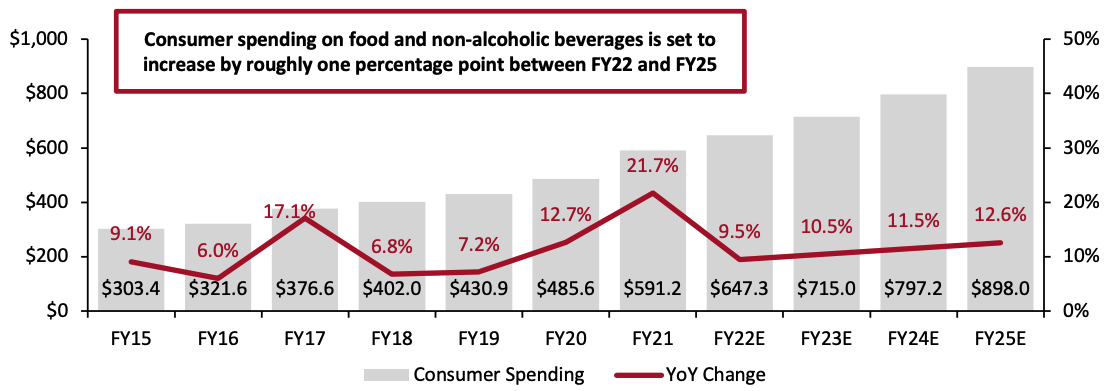

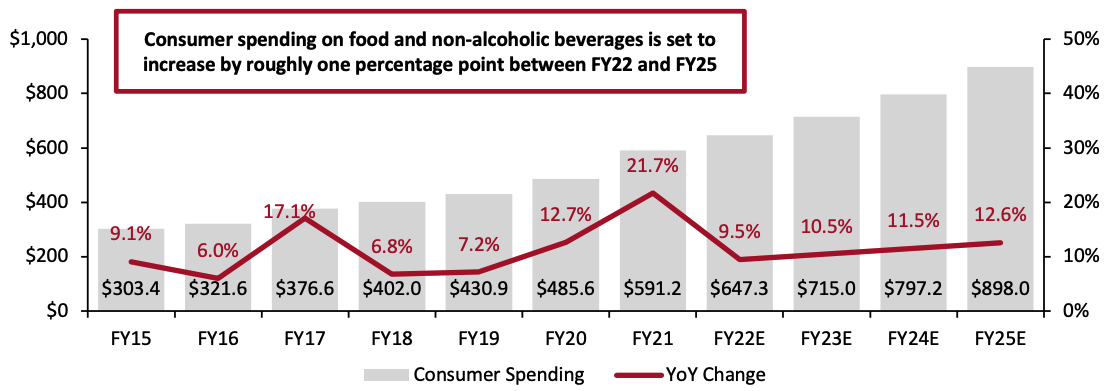

The food market in India is worth $600 billion and is growing quickly. Fiscal 2021 (in India, the fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31) saw increased consumer spending on food and non-alcoholic beverages due to pandemic-fueled panic buying. Due to these strong comparatives, we expect growth in consumer spending on food and non-alcoholic beverages to have moderated in fiscal 2022, with the sector totaling $647.3 billion (up from $591.2 billion in fiscal 2021), based on Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) data.

Spending will likely remain strong, and we estimate that it will increase and by roughly one percentage point each year to reach $898 billion in fiscal 2025 (see Figure 1). This increased consumer spending provides opportunities for international grocery retailers to scale up their investments in the country’s organized retail sector.

Figure 1. India: Consumer Spending on Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages (Left Axis; USD Bil.) and YoY Change (Right Axis; %)

[caption id="attachment_145194" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31

Fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31

Conversions to USD are at average 2021 exchange rates

Source: MOSPI/Coresight Research[/caption]

The consumer market and growth momentum in India make it an attractive investment destination. The country has the second-largest population in the world (1.3 billion people) and is one of the fastest-growing economies. According to the Economic Survey 2022 from the Ministry of Finance (based on data and analysis from other ministries), India’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate will hit 9.2% in FY22—one of the fastest growth rates among major economies.

International Grocery Retailers in India: Coresight Research Analysis

Key Characteristics of The Indian Grocery Market and Consumers

- Highly fragmented market: The grocery business in India operates across diverse channels, ranging from a few large modern hypermarkets and supermarkets to smaller convenience stores and kirana stores to regional farmers’ markets, roadside sellers and vendors that sell produce in pushcarts. According to a June 2021 survey by Global Agriculture Information Network and Euromonitor International, there were 12.8 million grocery retail outlets in India in 2021, including traditional and modern retailers, up from 12.4 million in 2013.

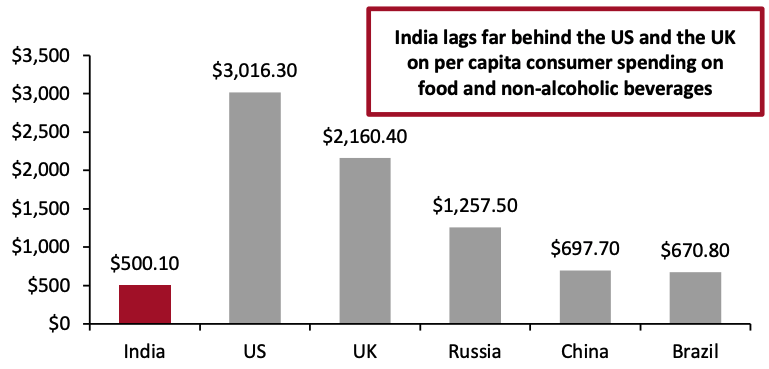

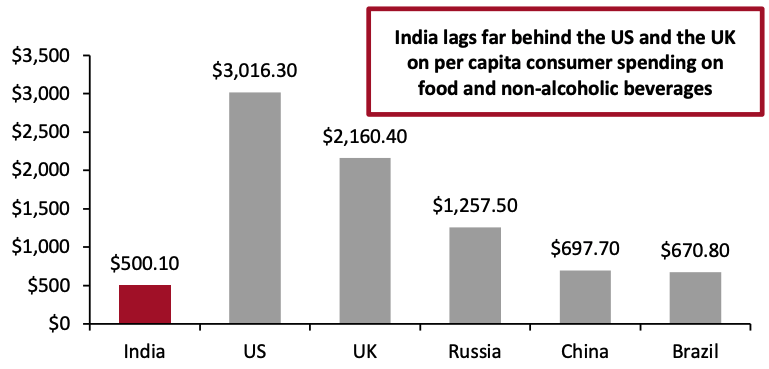

- Lower average consumer spend: Generally, consumers in less economically developed countries direct a greater share of their spending to basic retail categories, such as food, than consumers in more economically developed countries. Based on data from MOSPI, we estimate that 80% of Indian consumers’ total retail spending went to food and non-alcoholic beverages in fiscal 2021. Despite India’s high-growth trajectory and large population, per capita consumer spend on food and non-alcoholic beverages in India is relatively lower than that seen in the US or the UK and other BRIC nations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverage Per Capita Consumer Spending, 2020 (USD)

[caption id="attachment_145195" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Eurostat/IMF/Statista/United Nations/World Bank

Source: Eurostat/IMF/Statista/United Nations/World Bank[/caption]

- Regional culture and weather: India’s culture and weather vary greatly across regions, heavily influencing the food and diet of its people. For example, rice is the staple grain in Southern India, while wheat is predominant in other parts of the country.

- High proportion of vegetarians: According to an April 2021 survey by consulting company The Hartman Group, 24% of Indian adults are vegetarians. By comparison, 5% of US consumers and 4% of China consumers are vegetarians. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development indicates that, in 2022, India has one of the lowest meat-consumption rates in the world, at 5kg per capita compared to 25.3kg per capita in the US and 11.3kg per capita in the UK. Religious observance is one of the chief reasons for low meat consumption in India.

- Reliance on dry food and staples: Indian consumers rely heavily on cereals, grains and grams (dried legumes) to form their daily diet. Fresh produce and dairy are also key constituents. Data from Deloitte’s “India Food Report 2018” indicate that dairy and cereals constituted 40% of the food consumed in India. However, changing consumption patterns and health consciousness in India have resulted in a shift in consumption to protein over carbohydrates.

- Concept of maximum retail price: In India, federal laws stipulate that consumer-product manufacturers determine the maximum price at which their products are sold, and that they must print that price on product packaging. The government instituted this regulation to protect consumers by restricting retailers from selling goods at artificially inflated or deflated prices. The atmosphere in Indian grocery retail stores is typically highly promotional, so a fixed ceiling price protects consumers from being overcharged, while a floor price protects smaller retailers from the larger retailers that charge less to attract customers.

Opportunities in Indian Grocery Retail and Barriers to Entry

Opportunities

India’s grocery sector offers many opportunities for growth, some of which we detail below.

- Young, Working Population

India has the second-highest population in the world, at nearly 1.4 billion people as of December 2021, with an average age of 28.4 years, according to Worldometer (based on United Nations data). Furthermore, 67.4% of the total population are aged 15–64 years old (working age), according to the United Nations Population Fund’s 2021 data.

The urban population grew from 33.6% of India’s total population in 2017 to 34.9% in 2020, according to World Bank data. Urban consumers have more disposable income than rural consumers, so increased urbanization has also resulted in a rising per capita income—which grew by 65% between 2010 and 2019, from $4,190 to $6,920, according to World Bank data. The urban working class prefer to shop at organized food retail shops, due to convenience and the variety available at those stores.

- High Employment in Farming and Agriculture

The agricultural sector employs the greatest proportion of workers in India, at 42.6% in 2019, according to World Bank data. Farmers have strong unions in India that are entitled to subsidies from the government. Large international players can leverage their scale to engage in direct negotiations with farmers for price discounts and cut out intermediaries, which would result in a win-win situation for both parties.

- Proximity to Source and India’s Landscape for Cultivation

Foreign direct investment (FDI) norms stipulate that a major portion of merchandise sold is sourced from India, as the country is largely agricultural land and a significant portion of the population works for the agricultural sector. Launching sourcing factories and offices close to these agricultural areas would enable retailers to efficiently transport food to market, offering freshness and an edge over competitors.

- The Rise of Health-Conscious Consumers

The pandemic has resulted in consumers placing heightened emphasis on health and wellness, including eating more organic, nutritious foods that boost the immune system. According to an August 2020 paper by TechSci Research entitled “India Immunity Boosting Packaged Products Market,” the Indian immunity-boosting packaged products market is set to reach $347 million by fiscal 2026 due to increasing focus among consumers on preventative health. The organic food industry also saw a 25%–100% spike in sales in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic times, organic industry-focused magazine

Pure & Eco India revealed. Bengaluru-based organic retail chain The Organic World and food brands Organic Tattva and 24 Mantra Organic all reported increased sales in 2020. These changes present opportunities for grocery brands and retailers to add healthier, premium and organic foods into their product ranges to drive sales.

- Increasing Demand for Convenience Foods

Lifestyle changes are leading to convenience taking priority among Indian consumers who are less willing to spend time on food preparation. Convenience foods (also known as ready-to-eat products) require no, or minimal, effort to cook—they may just need heating up in a microwave, for example. Growing demand coupled with higher disposable incomes presents opportunity for grocery brands and retailers to establish and expand their presence in the convenience foods market.

As more Indians travel around the world, their desire to recreate international cuisines at home is growing. Many ingredients and equipment required to prepare international dishes are available only at modern retail stores, making them the preferred shopping destinations for those interested in international cuisines.

Barriers to Entry

Before international retailers can take advantage of the opportunities in India’s grocery sector, they must overcome a few social, commercial and political barriers to entry that exist due to the country’s diversity and complexity.

- Lengthy Bureaucratic Procedures and Loose Food Safety Regulations

Setting up a presence in India involves going through incredibly lengthy bureaucratic procedures. Also, food safety regulations in India are not as stringent as in the West. Industry observers state that farmers follow strict international regulations in organic food cultivation and labeling for exports. However, they do not follow the same for products sold domestically. As international retailers care about their image and reputation on products sold both domestically and internationally, strict regulation is an issue the government needs to address to attract more international retailers.

- Confusing Rules and Political Uncertainty

The absence of a comprehensive, consolidated document and government policies on FDI leads to a lack of clarity for international players looking to invest in India. The prevailing policy is occasional updates and statements in isolation, which do not provide a complete picture. Furthermore, investment decisions are at the discretion of various state governments that decide whether they should allow foreign retailers to open and operate. Political uncertainty is another concern because political parties focus on populist measures rather than streamlining policies and procedures for FDI and other investment opportunities.

- Unorganized Infrastructure

As India’s food retail sector is predominantly unorganized, there is a lack of proper infrastructure. Warehouses, cold-storage facilities and other necessary links in the supply chain are inadequate. According to Food and Agricultural Organization estimates, inefficient supply chains and fragmented food systems lead to 40% wastage of food produced in India. Furthermore, the United Nations Environment Program’s “Food Waste Index Report 2021” reveals that India’s household food waste is 50kg per capita per year, which translates to 68.7 million tons per year.

- Growing Online Penetration and the Rise of E-Grocers

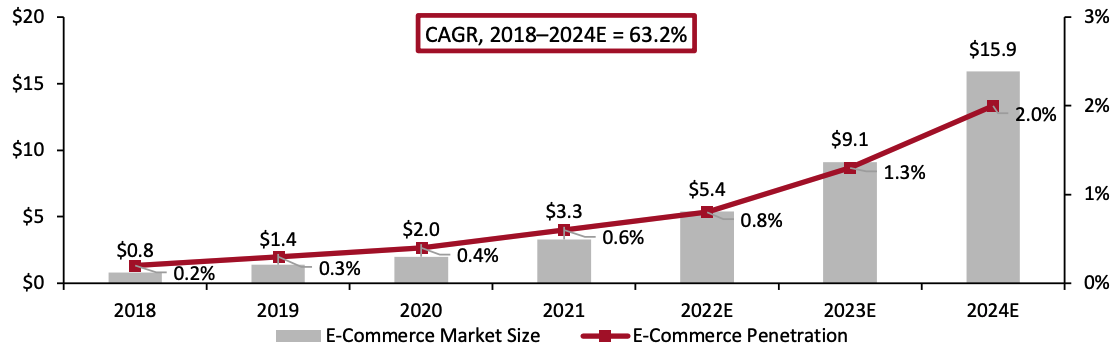

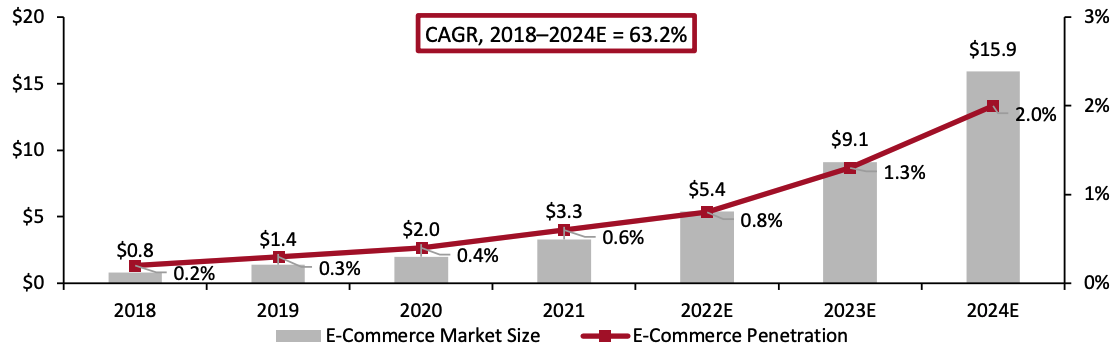

The pandemic led to a shift toward online channels, fueled by already increasing Internet and smartphone penetration, the boom of digital payments and government initiatives promoting the digital economy and digital literacy. These factors are likely to support further growth of online grocery purchasing in India, alongside consumer demand for convenience and preferences for an omnichannel shopping experience. According to an April 2020 survey by global data and insights firm Netscribes and

The Times of India newspaper, India’s grocery e-commerce market is set to total $3.3 billion in 2021 and will grow to $15.9 billion by 2024. Coresight Research estimates that e-commerce penetration in the Indian grocery market will increase from 0.6% to 2.0% in the same period (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. India: Grocery E-Commerce Market Size (Left Axis; USD Bil.) and E-Commerce Penetration (Right Axis; Online Sales as a % of Overall Grocery Sales)

[caption id="attachment_145197" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Netscribes/The Times of India/Coresight Research

Source: Netscribes/The Times of India/Coresight Research[/caption]

An expanding portfolio of products and express delivery services drive the growth of e-grocers. Domestic players BigBasket and Blinkit are the most prominent currently and have been slowly gaining market share in dry food retail, as has Amazon. Online marketplaces offer retailers the flexibility to display a wider assortment and range than could be stocked in a physical store, and big e-grocers also have logistics and other operational functions that ease the delivery of products from producer to consumer. Any new offline entrants in the Indian grocery sector will need to assess the threat from the rapidly growing online segment.

- Numerous Intermediaries in the Supply Chain

Food producers often work directly with retailers in urban areas, but must engage distributors or super stockists to supply to retailers in lower-tier cities and less-connected neighborhoods, reducing producers’ margins.

Key International Players in Indian Grocery Retail

As of 2022, there are two major international players in Indian grocery retail: Spar and Tesco. Walmart was operational through its Best Price stores, but e-commerce firm Flipkart acquired Walmart India’s Best Price cash-and-carry stores and renamed them Flipkart Wholesale in July 2020. Considering the grocery market in India and the relatively smaller number of international players, there is the possibility for many more to enter in the future.

We present key metrics for Spar and Tesco in Figure 4 and discuss each company in detail below.

Figure 4. Key International Players in Indian Grocery Retail

[wpdatatable id=1877]

Source: Company reports/S&P Capital IQ/Coresight Research

Spar

Spar Hypermarkets debuted in India in 2008 through a strategic collaboration between Dubai-based Landmark Group’s Max Hypermarkets India Private Limited and Amsterdam-based Spar International.

Spar India operates 25 stores in nine Indian cities, including four metro cities. It offers a wide range of products, including daily essentials, dairy and fresh produce, CPG food, home care, health and beauty, men, women and kids’ fashion, toys and baby products. It also offers private-label products such as Spar Select, Spar and Best Price.

[caption id="attachment_145198" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Spar store at Marina Mall in Chennai (left) and Farmers’ Market inside Spar store selling staples (right)

Spar store at Marina Mall in Chennai (left) and Farmers’ Market inside Spar store selling staples (right)

Source: Company website[/caption]

- Performance and Growth Strategy

Spar India expanded its online channels as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic, when most of its hypermarkets were shut down between March and June 2020. As a result, its India sales declined by 58.9% to €77.6 million ($86 million) in fiscal 2021.

Freshness in delivering products is one of Spar India’s core values, and the company has also introduced its “Farmer’s Market” concept, where it procures local produce direct from farmers and transports it to company collection centers. At these centers, the produce is graded and finally delivered to Spar stores across the country, with a focus on quick turnaround to ensure freshness.

The stores also feature “Freshly,” a dedicated section of value-added services to customers. In this section, locations offer freshly made consumables such as fresh fruit juices, salads and other food items.

Spar India offers a tech-powered experience to its customers as part of its vision to become the most engaging and innovative hypermarkets in India. Spar stores are equipped with a food kiosk–an interactive technology that provides recipes to customers with a single click, enabling them to purchase the correct ingredients and quantity for a focused shopping experience.

Stores also come built-in call facility for staff support when needed and self-checkout kiosks for a seamless checkout experience.

Spar India has also partnered with pushcart vendors in different localities to enable fresh produce delivery to customers’ doorsteps. The initiative, named Spar on Wheels, operates on a click-and-collect model and has a strong online presence through the company website.

Spar’s focus on innovative in-store technologies and doorstep delivery partnerships to increasingly omnichannel Indian consumers helps to differentiate the company from the competition. Meanwhile, Spar’s direct affiliation with farmers for local produce can be leveraged to augment its private-label offerings.

However, Spar needs to implement strict quality control measures for its locally sourced products and those delivered through pushcart vendors to ensure consistency and quality in its offerings.

Tesco

Tesco entered the Indian market in 2008, through the entity Trent Hypermarket Private Limited (THPL), a JV between Tesco and Tata Group company Trent Limited. THPL operates the Star Bazaar retail business, which has two formats—Star Hyper and Star Market.

Star’s hypermarket, Star Hyper, offers a wide range of products, including food and grocery, fresh produce, bakery items and beauty and household goods. It also deals in apparel and footwear through its Zudio brand.

Star’s supermarket, Star Market, advertises itself as a one-stop outlet that fulfills customers’ monthly and top-up needs for groceries, fresh produce, FMCG products, personal grooming items and general merchandise.

Star currently operates 21 stores across five cities: Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolhapur, Mumbai and Pune.

[caption id="attachment_145199" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Star Market location

Star Market location

Source: Company website[/caption]

- Performance and Growth Strategy

THPL revenue declined by 2.3%, year over year, to ₹12.1 billion ($159 million) in fiscal 2021. Going forward, it will primarily focus on engaging with more than 800 farmers to offer fresh foods to consumers at affordable prices. It also plans to expand its private-label packaged foods and beverages, home care and personal care offerings.

THPL’s expansion in India in recent years has been slow, and the company has rationalized its store real estate. THPL’s hypermarket stores now have an average size of between 20,000 square feet and 30,000 square feet; in previous years, the average size was between 40,000 square feet and 80,000 square feet.

Previously, the company also operated a format called Star Daily—neighborhood stores averaging between 2,000 square feet and 5,000 square feet in size and selling grocery, vegetables, fish and poultry. However, all 20 Star Daily stores shut down in 2018.

THPL’s reduced store sizes will help save on operating costs including rent, manpower, electricity and inventory holding, which might reflect in better profitability, generally measured in terms of sales per square feet. THPL can also leverage its private-label and affordable-price-point offerings for mass selling to achieve better retail margins.

Fresh produce is subject to price fluctuations. THPL might occasionally take a hit—for example, during the monsoon season—while sourcing through regional farmers.

Other Developments by International Players

- 7-Eleven Enters India Through Reliance Retail

In October 2021, American convenience-store chain 7-Eleven signed a master franchise agreement with Indian retail giant Reliance Retail Ventures. The same month, it opened its first store in Andheri, Mumbai, and currently plans to expand its store portfolio to key neighborhoods and commercial areas in Mumbai. Reliance Retail claims that 7-Eleven will be the first convenience store of its kind in India, offering refreshing ready-to-eat food and beverages, daily essentials and on-the-go services.

Previously, in February 2019, 7-Eleven entered into a master franchise agreement with Indian conglomerate Future Group-owned Future Retail to operate 7-Eleven stores in India. However, in October 2021, Future Retail announced the mutual termination of the agreement stating that 7-Eleven could not meet the store opening target or the payment of franchisee fees.

- Reliance Blocks Amazon’s Move To Become India’s Number-One Retail Player

In 2019, Amazon partnered with India-based department store retail chain Future Group and invested $200 million to acquire a 49% stake in Future Coupons, the group’s promoter entity. Following the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and the resulting setback in business, Future Group decided to sell some of its assets to Reliance Retail, which it agreed to buy for $3.4 billion.

However, according to Amazon, the deal with Future Group included non-compete clauses restricting the group from selling its retail assets to certain rivals, including Reliance Retail. The deal also mandated the settlement of any disputes under the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. Amazon then approached the Singapore arbitrators and stopped the sale of Future Group assets to Reliance. Both parties also challenged each other’s move with lawsuits in Indian courts, including the Supreme Court of India.

Despite the lawsuits, on February 25, 2022, Reliance, which was not publicly involved in the dispute, started executing a de facto takeover of 500 key stores in Future Group’s retail network. Previously, Reliance Retail’s parent organization, Reliance Industries Limited, subleased store space to Future Retail. The debt-laden Future Group could not pay the rent and Reliance absorbed many of Future’s leases, resulting in the takeover. Now, the stores are part of the Reliance Retail group.

As a result, Reliance has over 1,000 supermarkets in India, and Future Group has 1,500. The takeover boosted the retail footprint of Reliance Retail, providing a significant advantage in India’s $800 billion retail market.

Following the takeover, Amazon called for cordial talks with Future Group to end the dispute. After talks for an out-of-court settlement failed, Amazon approached the Supreme Court of India with a plea to resume proceedings regarding the deal. As of the time of this report’s publication, a verdict has not been reached.

- Amazon Currently Operates in the Sector Through Its Online Fresh Stores

In August 2019, Amazon launched its Amazon Fresh grocery delivery service in India via Amazon.in for select zip codes in Bangalore. The service offers over 5,000 fresh produce, dairy, meat, dry groceries, packaged food, personal care and home care products, with a selectable, two-hour delivery slot between 6:00 a.m. and midnight. In November 2020, Amazon expanded its Amazon Fresh service to four more Indian cities. Furthermore, to facilitate product storage and improve the frozen food infrastructure, it also expanded its network of Amazon Fresh distribution centers to more than 25 locations.

A year later, in November 2021, Amazon unified its grocery business, integrating its formerly separate Pantry service into the Amazon Fresh online portal. The new platform enables customers to buy both bulk groceries and fresh produce across 300 cities in India. Reliance Retail’s JioMart, which offers fresh produce, groceries, home care and personal care products, is a direct competitor to Amazon Fresh in India. To compete with Amazon, JioMart has expanded into other product categories including fashion, home essentials and lifestyle products.

These recent developments make foreign investors skeptical about investing in India, despite the strides made in its ease of doing business and FDI policies, discussed in the next section.

Economic Reforms in Grocery

The Indian government’s various initiatives over the last three decades to gradually open up the economy helped to ease international retailers’ entry into the country. As seen above, international grocery retailers operating in India largely remain in the hypermarket format under organized retail. They also have a strong online presence through their own websites and mobile apps, focusing on in-store and other technologies to offer a seamless shopping experience to attract customers.

However, India-based hypermarkets and supermarkets such as Big Bazaar, Spencer’s, Reliance Mart and other prominent regional players still offer stiff competition to international and online retailers in terms of their product offerings and price points, due to longstanding barriers to entry.

We outline some of the recent, major milestones in the liberalization of India’s economy in Figure 5, which we then discuss in more detail.

Figure 5. Timeline of FDI Liberalization in India

| 2020 |

| Government mandates approval for FDI by entities located in countries that share a land border with India, irrespective of the sector or level of investment. |

| 2019 |

| Government allows single-brand retailers to sell online without the need to open physical stores first.

Government also relaxes provisions for compliance to 30% mandatory local-sourcing requirements. |

| 2018 |

| Government revises FDI policy for e-commerce, including a regulation that marketplaces cannot have exclusivity agreements with vendors, cannot control prices and cannot hold equity stakes in vendors. E-commerce marketplaces given one month to comply and must submit certificates stating compliance annually. |

| 2017 |

| Government allows FDI of up to 100% in food-only retail, including through e-commerce, subject to approval and food sold must be produced and manufactured in India. |

| 2016 |

| Startup India campaign introduced. |

| 2015 |

| Make in India initiative introduced.

Government aligns the FDI policy with the National Industrial Classification Code, a federal statistical standard to develop and maintain databases of economic activity. |

| 2012 |

| Government allows FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail and removes FDI cap on single-brand retail, increasing the limit to 100%. |

| 2008 |

| Ruling party proposes introducing FDI in multibrand retail but fails to gain parliamentary approval. |

| 2006 |

| Government caps FDI in single-brand retail at 51%, subject to approval. |

| 1997 |

| Government permits FDI of up to 100% in wholesale, under the automatic route. |

| 1991 |

| Selected sectors open to foreign investment of up to 51%, under the automatic route (i.e., no government approval required). |

Source: IBEF/Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India/TechSci Research/Coresight Research

Foreign investors have been allowed to invest in and operate direct wholesale stores in India under the automatic route (i.e., without government approval of the investment) since 1997. This enabled cash-and-carry businesses—such as Metro Cash & Carry—to open stores in India much earlier than international retailers.

In 2012, the government removed the cap on single-brand retail investment and allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail, including department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands, subject to government approval.

Beginning in February 2017, the government has allowed 100% FDI in the sale of food products that are manufactured or produced in India, including through e-commerce. The government stipulates retailers must clearly separate their food-only businesses from their non-food businesses for regulatory purposes.

In 2018, the government revised its FDI e-commerce policy, including a regulation that marketplaces cannot have exclusivity agreements with vendors, cannot control prices and cannot hold equity stakes in vendors. E-commerce marketplaces were given one month to comply and must submit certificates stating compliance annually.

In August 2019, the government began allowing single-brand retailers to launch e-commerce operations without needing to establish a brick-and-mortar presence, which had previously been the case. The government also relaxed provisions for compliance to a 30% mandatory local sourcing requirement.

In April 2020, the government mandated that all FDI by entities in countries that share a land border with India must seek approval before investing, irrespective of sector or level of investment. Countries that share a border with India include Pakistan, Bangladesh, China, Nepal, Myanmar and Bhutan.

Below we summarize the FDI policy for various business types under the Retail and E-commerce sector (Figure 6).

Figure 6. FDI Policy for Different Types of Businesses Under the Retail and E-Commerce Sector

[wpdatatable id=1878]

Source: InvestIndia

With all these regulations and allowances, various international retailers have employed different routes to doing business in India.

Entry Routes for Foreign Brands and Retailers in India

The government has established several routes—both non-FDI and FDI based—through which international players can enter the country for retail trade.

There are two non-FDI routes:

- Licensing—Under this method, the owner of the brand (the licensor) leases the rights to use the brand name to the retailer (the licensee), allowing the retailer to stock and sell branded merchandise.

- Franchising—Similar to licensing, franchising allows a retailer (the franchisee) to use a brand’s (franchisor’s) intellectual property, as well as its business model, marketing strategy and distribution model to sell the brand’s goods. For example, in India, Max Hypermarkets owns the rights to operate stores under the Spar brand name.

Meanwhile, there are four FDI methods through which international retailers can sell goods in India:

- Joint venture—A JV is an enterprise in which two or more firms have pooled their capital and other resources. The 50/50 JV between British retailer Tesco and Trent Hypermarket is the most prominent example of this method currently employed in Indian grocery retail.

- Wholly owned subsidiary—Under this method, an organization (the parent or holding company) sets up a new company that is incorporated as a domestic business in India. The entire equity stake of the subsidiary is owned by the parent company. Metro Cash & Carry and Walmart’s Best Price (now renamed Flipkart Wholesale) stores operate as wholly owned subsidiaries.

- Limited-liability partnership (LLP)—With an LLP, the partners in a firm have limited liabilities; i.e., one partner cannot be held responsible for another partner’s mismanagement of the company.

- Extension of the foreign entity via a liaison office, branch office or project office—International companies can also set up an office in India that represents their interests under one of the above structures. The establishment of a liaison office, branch office or project office is subject to further rules laid out by the Indian government and central bank.

What We Think

To enter India’s grocery retail sector, international grocery retailers should align their product range to suit the predominantly young Indian consumers—working age, middle-income, living in urban cities, health-conscious and variety-seeking—to drive sales and engagement.

They also need to consider the growing role of e-grocers such as BigBasket, Blinkit and Amazon (which have a significant first-mover advantage) and launch their online arms (particularly direct-to-consumer) to cater to online consumers.

International grocery retailers can consider India’s lower-tier cities if considering an offline expansion. These markets have relatively lower operating costs and consumers with higher disposable incomes.

With India’s increasing focus on attracting FDI, we believe that the government is likely to further liberalize FDI policies, including food products retail and multibrand retail trading, consolidating norms to facilitate more investment from international players.

We believe the country’s high-growth economy and rising organized retail penetration offer growth prospects for international grocery retailers through various entry routes, either by setting up direct operations in partnership with local players, providing their expertise in running grocery chains through franchises or the other routes listed above.

Implications for Brands/Retailers

- International brands and retailers can look at partnerships with Indian retail giants with robust supply chain networks to streamline their operations in the country upon entry.

- To compete with the e-commerce players and boost their back-end operations, international brands and retailers should leverage technology for warehouse automation and micro-fulfillment.

Implications for Technology Vendors

- Companies and startups offering innovative in-store technologies can look at partnerships with international grocery supermarket chains to rollout tech-powered experiences in their Indian stores.

Fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31

Fiscal year runs from April 1 to March 31 Source: Eurostat/IMF/Statista/United Nations/World Bank[/caption]

Source: Eurostat/IMF/Statista/United Nations/World Bank[/caption]

Source: Netscribes/The Times of India/Coresight Research[/caption]

An expanding portfolio of products and express delivery services drive the growth of e-grocers. Domestic players BigBasket and Blinkit are the most prominent currently and have been slowly gaining market share in dry food retail, as has Amazon. Online marketplaces offer retailers the flexibility to display a wider assortment and range than could be stocked in a physical store, and big e-grocers also have logistics and other operational functions that ease the delivery of products from producer to consumer. Any new offline entrants in the Indian grocery sector will need to assess the threat from the rapidly growing online segment.

Source: Netscribes/The Times of India/Coresight Research[/caption]

An expanding portfolio of products and express delivery services drive the growth of e-grocers. Domestic players BigBasket and Blinkit are the most prominent currently and have been slowly gaining market share in dry food retail, as has Amazon. Online marketplaces offer retailers the flexibility to display a wider assortment and range than could be stocked in a physical store, and big e-grocers also have logistics and other operational functions that ease the delivery of products from producer to consumer. Any new offline entrants in the Indian grocery sector will need to assess the threat from the rapidly growing online segment.

Spar store at Marina Mall in Chennai (left) and Farmers’ Market inside Spar store selling staples (right)

Spar store at Marina Mall in Chennai (left) and Farmers’ Market inside Spar store selling staples (right) Star Market location

Star Market location