Nitheesh NH

Introduction: A Large, Developing and Complex Market

The grocery retail landscape in India is markedly different from that in the West. It is a predominantly unorganized sector comprising general stores, kirana stores (mom-and-pop stores), convenience stores, informal street markets and stalls, and vegetable and fruit vendors that sell fresh produce on pushcarts. These types of vendor operate alongside modern grocery retail outlets that sell local produce, imported food and other products. While organized retail currently takes a relatively small share of the overall market, it is steadily growing. In this report, we examine the push of Western grocery retailers and wholesalers into India’s grocery landscape, look at the features of the Indian grocery market, and analyze the barriers to entry as well as opportunities in the sector.Indian Food Retail: A $287.5 Billion Market

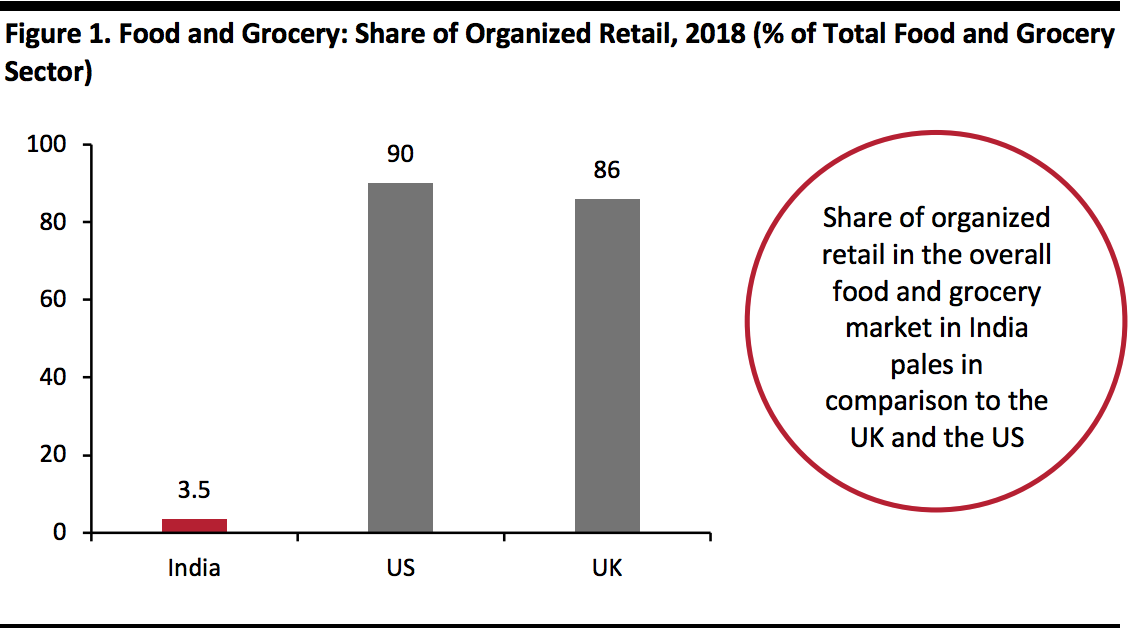

We begin by examining the Indian retail sector and the share that grocery holds, as well as some of the characteristics that are unique to the grocery market in India. The scale of the consumer market and growth momentum in India make it an attractive destination for investment. The country has the second-largest population in the world (1.3 billion people) and is one of the fastest-growing large economies. India’s food market is estimated to be worth $287.5 billion in 2020 according to data platform Statista. These estimates were calculated prior to the coronavirus outbreak; they also exclude sales of beverages and nonfood categories that grocery retailers would ordinarily sell. According to the latest estimates by Redseer, the penetration rate of organized brick-and-mortar retail in the food and grocery sector was just 3.5% in 2018, which is considerably lower than in countries such as the UK and the US, as depicted in Figure 1. Organized food and grocery retail is expected to grow at a 25% CAGR to reach a market share of 6.7% by 2023. It is worth noting that online retail accounts for a very small proportion of the food and grocery sector in India, only 0.2%. Redseer estimates that online grocery will rise to only 1.2% by 2023. [caption id="attachment_108095" align="aligncenter" width="580"] Source: Redseer[/caption]

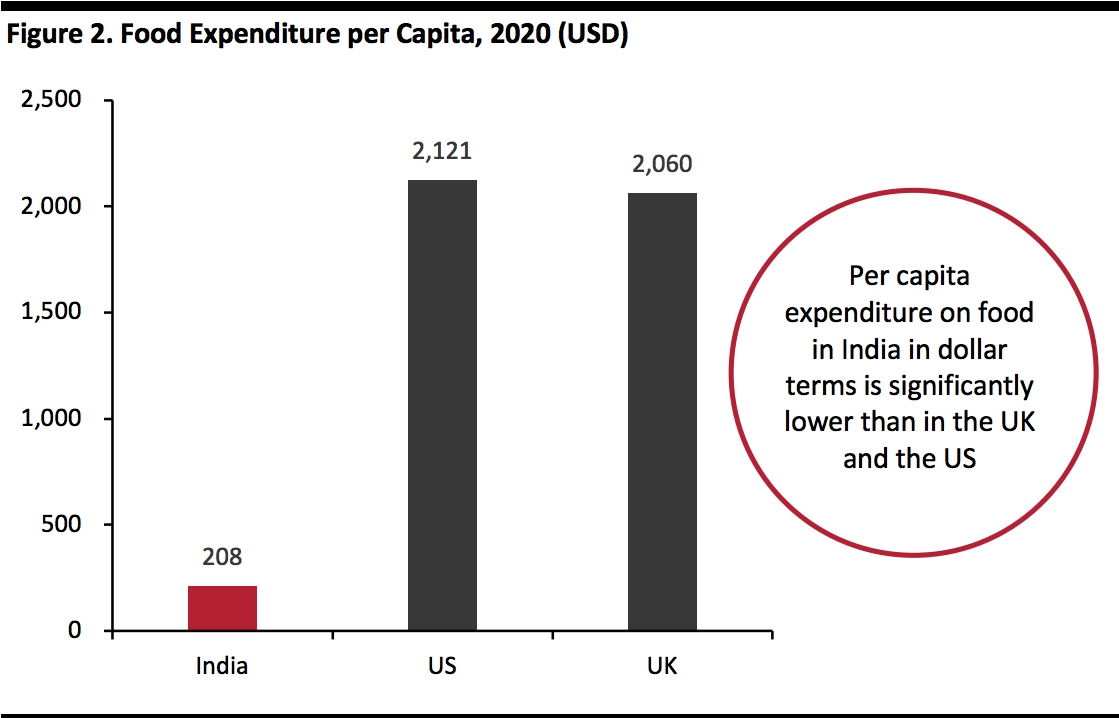

Food is a staple expenditure, and as a general rule, consumers in less economically developed countries direct a greater share of their spending to basic retail categories than consumers in more economically developed countries. Food, beverages and tobacco account for a much higher proportion of total spending in India than in Western markets such as the UK and the US.

Source: Redseer[/caption]

Food is a staple expenditure, and as a general rule, consumers in less economically developed countries direct a greater share of their spending to basic retail categories than consumers in more economically developed countries. Food, beverages and tobacco account for a much higher proportion of total spending in India than in Western markets such as the UK and the US.

Key Characteristics of Indian Grocery Consumers and Grocers

There are many characteristics unique to diverse and populous India that define its grocery landscape, including the following:- Low modern-retail penetration: Many Indians still transact through traditional retail channels rather than through modern retail channels. According to India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), modern-retail penetration is estimated to be about 10% in India in 2020. It is even lower in food retail, as discussed in the previous section.

- Highly fragmented market: Building on the first point, grocery vendors in India range from a few large, modern hypermarkets and supermarkets to many smaller convenience stores to numerous farmer’s markets, roadside sellers and vendors that sell produce on pushcarts near people’s homes.

- Small basket sizes: Despite India’s high-growth trajectory and large size, its consumers are less affluent than their peers in many other large economies and in the other BRIC nations, and they have considerably smaller average grocery basket sizes.

Source: Statista/Coresight Research[/caption]

Source: Statista/Coresight Research[/caption]

- Regional culture and weather: India’s culture and weather vary greatly across regions, and heavily influence the food and diet of its people in different areas. For example, rice is a staple grain in the South of India, while wheat is predominant in other parts of the country.

- High proportion of vegetarians: Some 30% of Indians are vegetarians, according to the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. In comparison, 10–12% of UK and US consumers are vegetarians, according to a 2013 Harris Poll. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development indicate that in 2016, India had one of the lowest meat-consumption rates in the world, at 3kg per capita. While religious observance is a primary reason for this, low meat consumption also tends to be associated with lower disposable income.

- Reliance on dry food: According to the India Food Report 2016, dry food comprises 35% of the grocery market in India, as consumers rely heavily on cereals, grains and grams (dried legumes) to form their staple diet. Fresh produce and dairy are also key constituents, together accounting for 33% of the Indian diet, according to the same report. Our on-the-ground research in India suggests that most consumers who shop through modern retail stores tend to buy the majority of their dry food and nonfresh produce at larger shops and supermarkets, while they buy fresh produce at neighborhood convenience stores and vegetable cart vendors.

- The concept of maximum retail price: In India, federal laws stipulate that consumer-product manufacturers determine the maximum price at which their products are sold, and that they print that price on product packaging. The government instituted this regulation to protect consumers by restricting retailers from selling goods at artificially inflated or deflated prices.The atmosphere in Indian grocery retail and wholesale stores is typically highly promotional, so a fixed ceiling price protects consumers from being overcharged, while a floor price protects smaller retailers from the larger retailers that charge less in order to attract customers.

Economic Reforms in Grocery Wholesale and Retail

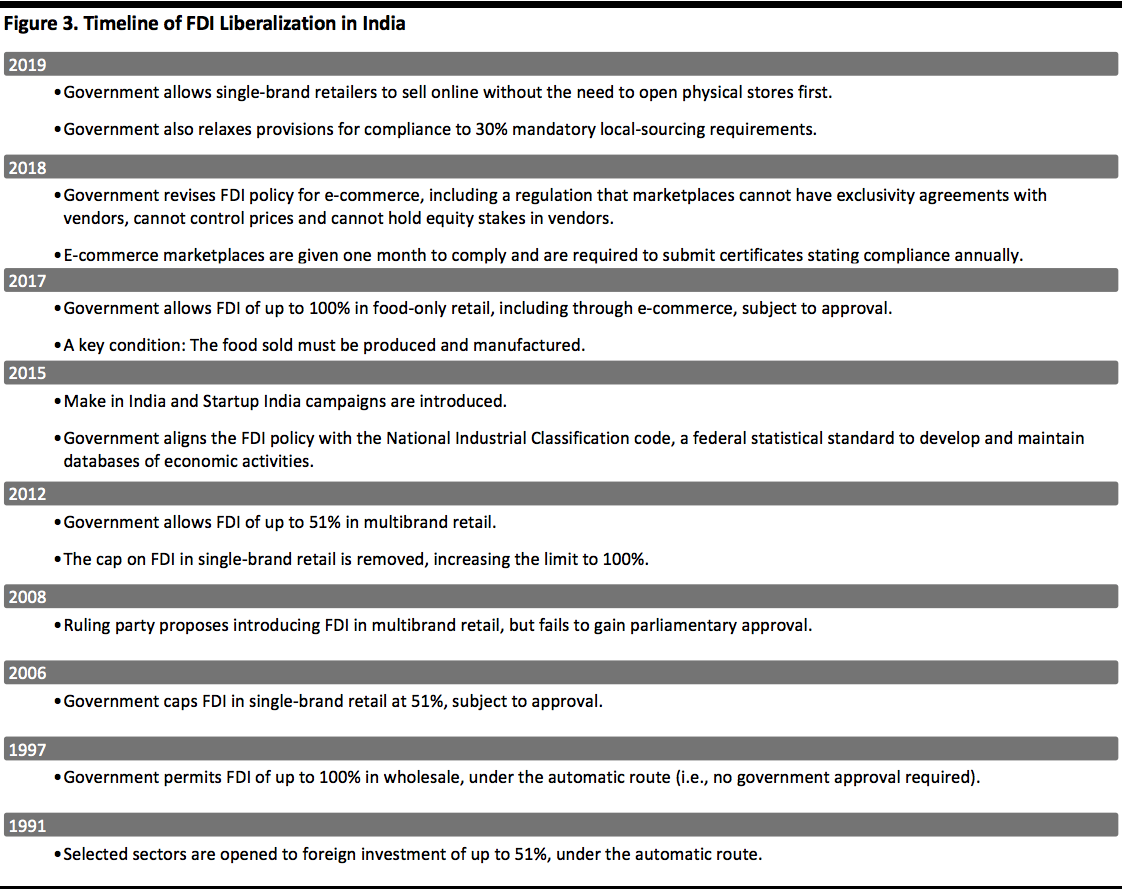

The Indian government’s initiatives over the last three decades to gradually open up the economy helped to ease international retailers’ entry into the country. The figure below illustrates some of the major milestones in the liberalization of India’s economy, which we then discuss in more detail. [caption id="attachment_108097" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: TechSci Research/IBEF/Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India/Coresight Research[/caption]

Foreign investors have been allowed to invest in and operate direct wholesale stores in India under the automatic route (i.e. without any requirement of government approval for the investment) since 1997. This paved the way for cash-and-carry businesses—such as Metro Cash & Carry—to open stores in India much earlier than international retailers. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, Carrefour and Walmart set up cash-and-carry formats to cater to wholesale consumers, as the retail sector in which they typically operate in their home and global markets was not yet open to foreign investment at the time.

The Indian government enforced its highly protectionist regulation of the retail sector until about 2006, when it first allowed FDI of up to 51% in single-brand retail, subject to approval. This meant that retailers such as Gap and Zara, which sold only own-brand products, were allowed to open stores in India in partnership with a local company, with a maximum ownership stake of 51%. However, in grocery, it is impractical for most retailers to sell only own-brand products.

In 2012, the government removed the cap on single-brand retail investment and also allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail (which includes department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands), subject to government approval.

From February 2017, the government has allowed 100% FDI in the sale (including through e-commerce) of food products that are manufactured or produced in India. The government stipulates that retailers clearly separate their food-only business from their nonfood business for regulatory purposes.

In 2018, the government revised its FDI policy for e-commerce, including a regulation that marketplaces cannot have exclusivity agreements with vendors, cannot control prices and cannot hold equity stakes in vendors. E-commerce marketplaces were given one month to comply and are required to submit certificates stating compliance annually.

In August 2019, the government began allowing single-brand retailers to launch e-commerce operations without the need to establish a brick-and-mortar presence, which had previously been the case. The government also relaxed provisions for compliance to 30% mandatory local sourcing requirements.

Taking stock of all these regulations and allowances, various international retailers have employed different routes to doing business in India.

Source: TechSci Research/IBEF/Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India/Coresight Research[/caption]

Foreign investors have been allowed to invest in and operate direct wholesale stores in India under the automatic route (i.e. without any requirement of government approval for the investment) since 1997. This paved the way for cash-and-carry businesses—such as Metro Cash & Carry—to open stores in India much earlier than international retailers. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, Carrefour and Walmart set up cash-and-carry formats to cater to wholesale consumers, as the retail sector in which they typically operate in their home and global markets was not yet open to foreign investment at the time.

The Indian government enforced its highly protectionist regulation of the retail sector until about 2006, when it first allowed FDI of up to 51% in single-brand retail, subject to approval. This meant that retailers such as Gap and Zara, which sold only own-brand products, were allowed to open stores in India in partnership with a local company, with a maximum ownership stake of 51%. However, in grocery, it is impractical for most retailers to sell only own-brand products.

In 2012, the government removed the cap on single-brand retail investment and also allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail (which includes department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands), subject to government approval.

From February 2017, the government has allowed 100% FDI in the sale (including through e-commerce) of food products that are manufactured or produced in India. The government stipulates that retailers clearly separate their food-only business from their nonfood business for regulatory purposes.

In 2018, the government revised its FDI policy for e-commerce, including a regulation that marketplaces cannot have exclusivity agreements with vendors, cannot control prices and cannot hold equity stakes in vendors. E-commerce marketplaces were given one month to comply and are required to submit certificates stating compliance annually.

In August 2019, the government began allowing single-brand retailers to launch e-commerce operations without the need to establish a brick-and-mortar presence, which had previously been the case. The government also relaxed provisions for compliance to 30% mandatory local sourcing requirements.

Taking stock of all these regulations and allowances, various international retailers have employed different routes to doing business in India.

Entry Routes for Foreign Brands and Retailers in India

The government has established several routes through which international firms can trade in India. Under the non-FDI route, there are two methods:- Licensing: Under this method, the owner of the brand (the licensor) leases the rights to use the brand name to the retailer (the licensee), allowing the retailer to stock and sell the branded merchandise.

- Franchising: Similar to licensing, franchising allows a retailer (the franchisee) to use a brand’s (franchisor’s) intellectual property, as well as its business model, marketing strategy and distribution model, in order to sell the brand’s goods. For example, in India, Max Hypermarkets owns the rights to operate stores under the Spar brand name.

- JV: A JV is an enterprise in which two or more firms have pooled their capital and other resources. The 50/50 JV between British retailer Tesco and Trent Hypermarket is the most famous example of this method being employed in grocery retail in India. Through the JV, the companies operate stores under the Star Bazaar and Star Daily banners.

- Wholly owned subsidiary: With this method, an organization (the parent or holding company) sets up a new company that is incorporated as a domestic business in India. The entire equity stake of the subsidiary is owned by the parent company. Metro Cash & Carry and Walmart’s Best Price stores operate as wholly owned subsidiaries. Carrefour also operated under this method in the years it did business in India.

- Limited-liability partnership: With this model, the partners in a firm have limited liabilities—i.e., one partner cannot be held responsible for another partner’s mismanagement of the company.

- Extension of the foreign entity via a liaison office, branch office or project office: International companies can also set up an office in India that represents their interests under one of the above structures. The establishment of a liaison office, branch office or project office is subject to further rules laid out by the Indian government and central bank.

Key International Players in Indian Grocery Retail

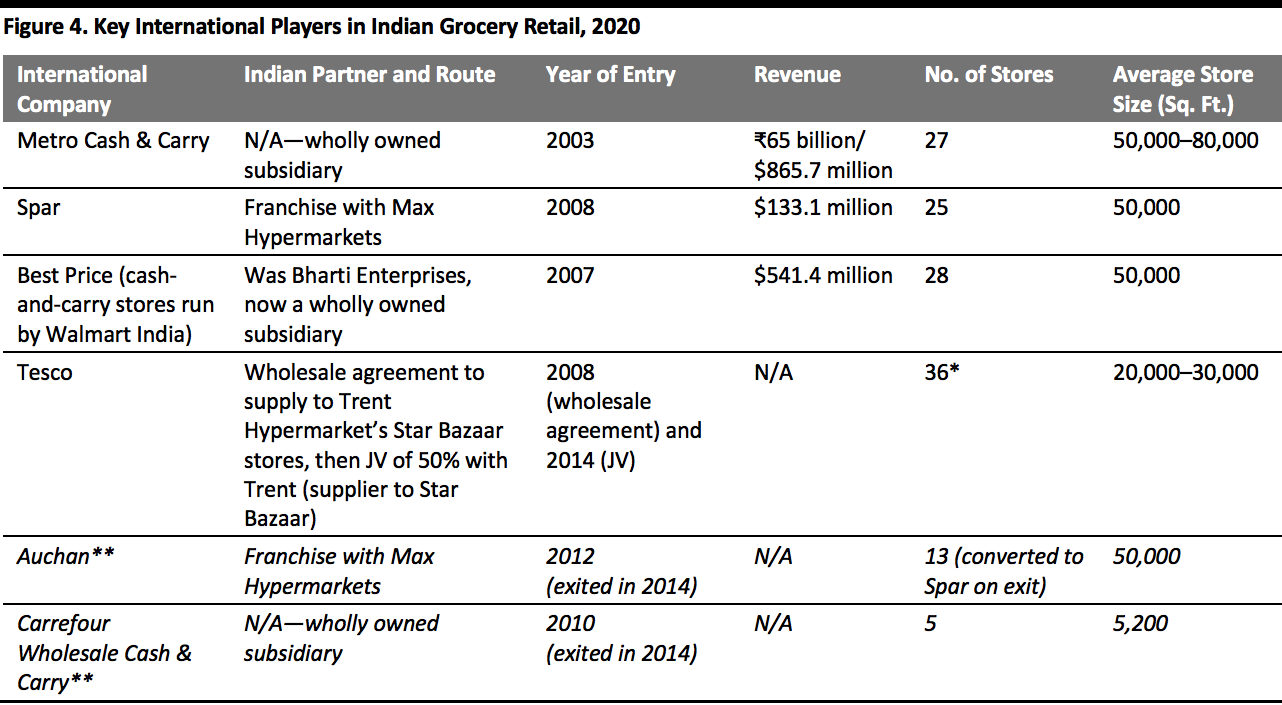

In this section, we discuss some of the major international names operating grocery retail and wholesale stores in India and the companies with which they have partnered. Currently, there are four key international players in Indian grocery retail and wholesale: Metro Cash & Carry, Spar, Tesco and Walmart (through its Best Price stores). French retailers Auchan and Carrefour each operated in the country for a few years, but exited due to a lack of clarity about foreign investment in food retail; we include them in Figure 6, for comparison purposes. [caption id="attachment_108098" align="aligncenter" width="700"] *Tesco, through its JV with Trent, operates 10 hypermarkets and 26 supermarkets under the Star banner

*Tesco, through its JV with Trent, operates 10 hypermarkets and 26 supermarkets under the Star banner**No longer operating in India

Source: Company reports/S&P Capital IQ[/caption] Metro Cash & Carry Metro Cash & Carry launched its operations in India in 2003. It currently operates 27 wholesale distribution centers in the country: six in Bangalore; four in Hyderabad; two each in Delhi and Mumbai; and one each in Ahmedabad, Amritsar, Ghaziabad, Indore, Jaipur, Jalandhar, Kolkata, Lucknow, Meerut, Nasik, Surat, Vijayawada and Zirakpur. Metro’s core customer base includes small retailers and kirana stores, hotels, restaurants, caterers, corporates, small and medium enterprises, offices, companies and institutions and self-employed professionals. Metro Cash & Carry offers a variety of products, ranging across categories such as fruits and vegetables, general grocery, bakery and frozen products, fish and meat, household goods, health and beauty products and confectionery. Some of the private-label brands that the company operates include Aro, Fine Life, Rioba, Metro Chef, Sigma, Tarrington House, Fairline and Lambertazzi. As of March 26, 2020, the company had temporarily shut down eight of its 27 outlets owing to the lockdown in India triggered by the coronavirus pandemic. [caption id="attachment_108099" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Metro Cash & Carry store

Metro Cash & Carry storeSource: Company website[/caption] Spar Spar Hypermarkets debuted in India in 2008; it was formed through a strategic collaboration between Dubai-based Landmark Group’s Max Hypermarkets and Amsterdam-based Spar International. Spar India runs operations in India through 25 stores in nine cities: Bengaluru, Chennai, Coimbatore, Ghaziabad, Gurugram, Hyderabad, Mangalore, New Delhi and Shimoga. In 2017, the company launched a new retail store concept called Spar S2 Format, under which it introduced specialized, experiential sections, such as Wonder Years for Kids, Beauty, Taste of India and Spar Natural, among others. The new store format also placed strong emphasis on leveraging technology to achieve better shopper engagement. Aligning with its core value of delivering fresh products, the company has also introduced its ‘Farmer’s Market’ concept, through which it procures local produce direct from farmers that is transported to the company’s collection centers. At these centers, the produce is graded and finally delivered to Spar stores across the country, with a focus on quick delivery to ensure freshness. Spar India stores also feature “Freshly,” which is a section focused on providing value-added services to customers. In this section, customers are offered freshly made consumables such as fresh fruit juices, salads and other food items. [caption id="attachment_108101" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Spar’s store at Marina Mall in Chennai.

Spar’s store at Marina Mall in Chennai.Source: Company website[/caption] Walmart (Best Price) Walmart arrived in India in 2007 and went on to open its first store in the country in Amritsar, Punjab, in May 2009. Walmart India then became a wholly owned subsidiary of Walmart Inc. in 2014. Currently, Walmart India operates 28 cash-and-carry stores in nine states across the country under the Best Price brand name. The company also operates two fulfillment centers, one each in Lucknow and Hyderabad. Its two newest outlets were both opened in the second half of 2019—one in Warangal city in the state of Telangana in September and another in Kurnool city in Andhra Pradesh in December. Best Price operates on a membership model; the majority of its 1 million-plus members are small resellers and kiranas. In March 2020, Walmart India announced the appointment of Sameer Aggarwal as its new CEO, effective April 1, 2020. Aggarwal began his stint with Walmart in 2018, when he was hired as Executive Vice President, and has been serving as Deputy CEO since January this year. Incumbent CEO Krish Iyer will retire from his position and take on a new role as advisor to Best Price, Walmart India. In the capacity of his new position as CEO, Aggarwal is expected to focus on enhancing the company’s digital and omnichannel services. [caption id="attachment_108102" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Best Price wholesale store in Warangal city in Telengana.

Best Price wholesale store in Warangal city in Telengana.Source: Company website[/caption] Tesco Tesco entered India through the entity Trent Hypermarket Pvt. Ltd (THPL), a JV between Tesco and Tata Group company Trent Ltd. THPL operates the Star Bazaar retail business, which has two formats—Star Hyper and Star Market. Previously, the company also operated a format called Star Daily—neighborhood format stores averaging between 2,000 and 5,000 square feet in size and selling grocery, vegetables, fish and poultry. However, all 20 Star Daily stores were shut down in 2018. Star’s hypermarket store format, Star Hyper, offers a wide range of products, including food and grocery, fresh produce, bakery, beauty and household goods. It also deals in apparel and footwear through its Zudio brand. Star’s supermarket format, Star Market, positions itself as a one-stop outlet that fulfills customers’ monthly and top-up needs for groceries, fresh produce, FMCG products and general merchandise. Star currently operates 10 hypermarkets and 26 supermarkets in cities across the country, including Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolhapur, Mumbai and Pune. THPL’s expansion in India in recent years has been slow, and the company has rationalized its store estate. Apart from discontinuing its Star Daily format, THPL’s hypermarket stores now have an average size of between 20,000 and 30,000 square feet; in previous years, the average size was between 40,000 and 80,000 square feet. [caption id="attachment_108103" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Star Market store in Khargar, Navi Mumbai.

Star Market store in Khargar, Navi Mumbai.Source: Star Bazaar/ Facebook[/caption] 7-Eleven Plots India Entry In addition to the major players discussed above, there are new international players vying to enter the Indian grocery retail landscape. Among these is 7-Eleven. In February 2019, Japanese-American international convenience-store chain 7-Eleven signed a master franchise agreement with Future Group-owned Future Retail to operate 7-Eleven stores in India. According to its expansion plan, the company’s focus for the first two to three years is set to be on opening stores only in Mumbai, with Future Group founder and CEO suggesting that the city could possibly see more than 1,000 stores set up eventually. 7-Eleven will open a cluster of stores in specific areas, rather than isolated individual stores. The retailer had initially planned to launch operations in 2019, but later postponed the plan to the end of the first quarter of 2020. However, following the outbreak of the coronavirus, it appears as if those plans are indefinitely delayed, and 7-Eleven has not made any recent announcements to officially clarify its plans.

Opportunities in Indian Grocery Retail and Barriers to Entry

In India’s organized grocery retail market, there are numerous homegrown modern retailers but only a handful of international retailers. Given the country’s diversity and complexity, there appear to be more social, commercial and political barriers to entry into the grocery market than there are in other retail segments—but there are many opportunities for growth in Indian grocery, too. Some of the underlying opportunities in the Indian grocery market are listed below:- The growing organic grocery segment and consumer preferences for healthier food: The organic grocery segment in India has been growing at a CAGR of 25% and is estimated to reach ₹100–120 billion ($1.3–1.6 billion) in 2020, according to a report by Assocham and Ernst and Young. The government has implemented policies to increase the farmland devoted to organic agriculture. Organic food currently constitutes a small but rapidly growing category across most modern grocery retailers in India, which cater largely to young, urban families.

- High employment in farming and agriculture: The agricultural sector employs the greatest proportion of people in India—around 43% in 2019, according to a modeled estimate by the International Labour Organization. Farmers have strong unions in India and are provided many subsidies by the government, so they have strong bargaining power. Large international players can use their scale to engage in direct negotiations with farmers and cut out intermediaries, which would result in a win-win situation for both parties, as well as supporting increased transparency in the supply chain.

- Proximity to source and India’s landscape for cultivation: FDI norms stipulate that a major portion of merchandise sold is sourced from India, as large parts of the country are agricultural areas and a large portion of the working population is employed in agriculture, as stated above. Locating sourcing factories and offices close to these agricultural areas would enable retailers to efficiently transport food from farm to market.

- Youthful, modern working population: India has one of the youngest populations in the world. Some 67% of the country’s 1.3 billion people were between the ages of 15 and 64 in 2018, according to World Bank estimates. The urban working class tends to prefer to shop at organized food retail shops, due to the variety available at those stores.

- Government plans and initiatives to boost foreign investment: The Indian government’s move to lift the cap on foreign investment in food retail indicates that it is open to growing the sector. Although the government has indicated that it does not intend to lift the restriction on the retailing of nonfood items in the same stores in which food is sold, many international retailers hope that it will open up the sector further in the near future.

- Widening palates and preferences for international cuisines: As more Indians travel around the world, their desire to try out international cuisines at home is growing. Many of the ingredients and much of the equipment required to prepare international dishes are available only at modern retail stores, making them the preferred shopping destinations for those interested in international cuisines.

- Lengthy bureaucratic procedures and loose food-safety regulations: Setting up any sort of establishment in India involves going through incredibly lengthy bureaucratic procedures, which need to be streamlined. Also, food safety regulations in India are not as stringent as in the West. While farmers do follow strict international regulations in organic food cultivation and labeling for products that are exported, they do not tend to follow them as carefully for products sold to the domestic market, according to industry observers. As the image and reputation of retailers and brands depend on the quality of the products sold, strict regulation is a pressing issue that the government needs to address in order to attract more international retailers.

- Inadequately developed infrastructure: As the majority of food retail in India is unorganized, there has been little reason and opportunity to develop infrastructure related to food retail. Warehouses, cold-storage facilities and other necessary links in the supply chain are inadequate. In fact, a government survey in 2016 found that India wastes approximately 67 million tonnes of food each year, worth about ₹920 billion ($12.2 billion), due to storage facilities that inadequately address pests, weather conditions and gluts in supply.

- Rise of e-grocers: Online food and grocery retail in India currently constitutes just 0.2% of the total market, but it is estimated to reach 1.2% ($10.5 billion) by 2023, according to a 2019 report by Redseer. The growth for e-grocers is driven by their expanding portfolio of products and express delivery services. Domestic players Bigbasket and Grofers are the most prominent players currently and have been slowly gaining market share in dry food retail, as has international giant Amazon. Stepping up its investment in the sector, Amazon—along with private-equity fund Samara—acquired grocery retail chain More in September 2018. Walmart-owned Flipkart, India’s largest homegrown online retail marketplace, has also entered the fray and acquired business-to-business fresh-produce supply-chain company Ninjacart in December 2019. Flipkart has registered a new entity called Flipkart Farmermart Pvt for its food retail business, and according to a report by business news website Moneycontrol, the company has reportedly set aside ₹25 billion ($333 million) to expand its grocery segment.There are several advantages for packaged-food suppliers in working directly with e-grocery players. Online marketplaces allow retailers to display a wider assortment and range than could be stocked at a physical store, and big e-grocers also have logistics and other operational functions in place that ease the delivery of products from producer to consumer. Any new entrants in the Indian grocery market will need to assess the threat from the rapidly growing e-grocery retail sector.

- Numerous intermediaries in the supply chain: Food producers tend to work directly with retailers in urban areas, but they need to engage distributors or super stockists to supply retailers in smaller cities and less-connected neighborhoods, which could reduce producers’ margins.

- Unplanned urbanization: Urban areas have been growing rapidly in India, but infrastructure has not evolved at the same pace. In some areas, roads are narrow and poorly maintained, making them unsuitable for large vehicles that carry products to market. Furthermore, a lack of mobile connectivity in remote areas makes it hard for companies to communicate effectively.