Nitheesh NH

Introduction: The Indian Apparel Retail Story

The apparel sector in India has been on a path of evolution in the last three decades, growing in leaps and bounds. Not too long ago, traditional clothing styles were widely preferred and embraced regardless of the availability of alternatives among most Indians, especially women. However, with increased disposable incomes, social and cultural transformations and enhanced access to affordable Western clothing, there has been a discernible shift in Indians’ sartorial preferences. Furthermore, the entry of international retailers such as Gap, H&M, Marks & Spencer (M&S) and Zara into India, powered by the opening up of the Indian economy, is inspiring other global retailers to follow suit. In this report, we examine India’s apparel retail market and its defining characteristics. We also look at the opportunities and threats that lay ahead as international retailers increasingly push into the market.Sizing the Indian Clothing Market

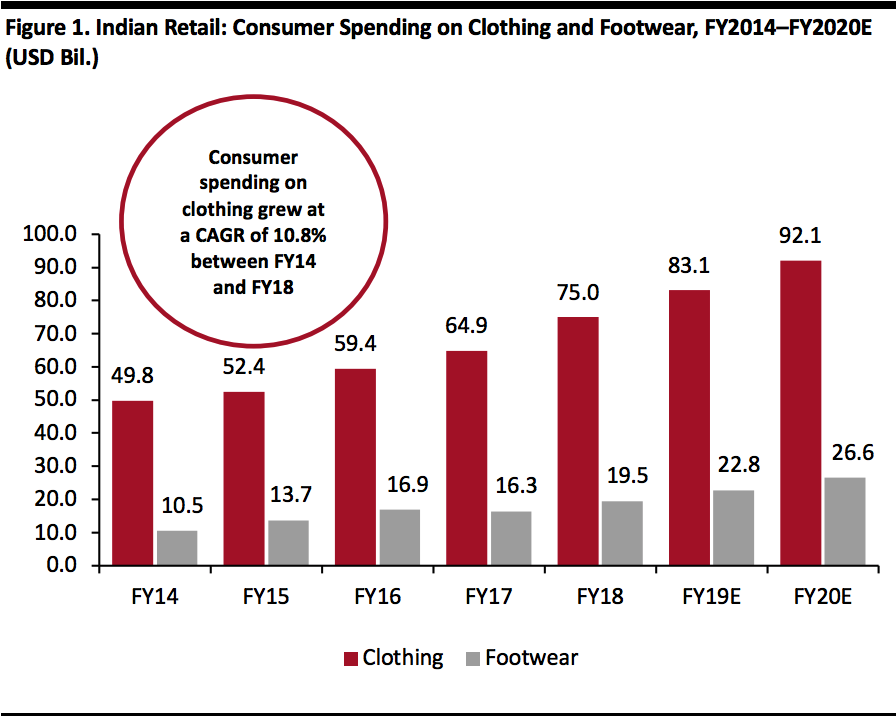

We begin by looking at the size of the market, key details of the Indian retail sector, apparel’s share of the retail sector and some of the characteristics that are unique to the Indian apparel market. Unsurprisingly India is becoming an increasingly popular destination for investment among international retailers, with the country housing the world’s second-largest population, of 1.3 billion people, and representing one of the fastest-growing large economies in the world. Apparel in India: A $92 Billion Market We estimate that consumer spending on clothing in India reached $92.1 billion at the end of fiscal year 2020 (ended March 31, 2020), having grown at a double-digit average annual pace in recent years. However, this upward trajectory is likely to grind to a halt: With the coronavirus pandemic wreaking havoc on retail overall, spending will take a significant hit in the current fiscal year. According to the MOSPI, Indian consumer spending on clothing reached $75 billion in the fiscal year ended March 2018, having grown at a CAGR of 10.8% between fiscal years 2014 and 2018 (latest), as shown in Figure 1. These figures are at fixed 2020 exchange rates to strip out the effects of currency fluctuations. For context, the Indian Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF) estimated the size of India’s overall retail sector to have reached $950 billion in 2018 and expects its value to reach $1.1 trillion by 2020, growing at a CAGR of 13%. [caption id="attachment_108932" align="aligncenter" width="580"] Fiscal years ended March 31; data converted to US dollars at constant 2020 exchange rates

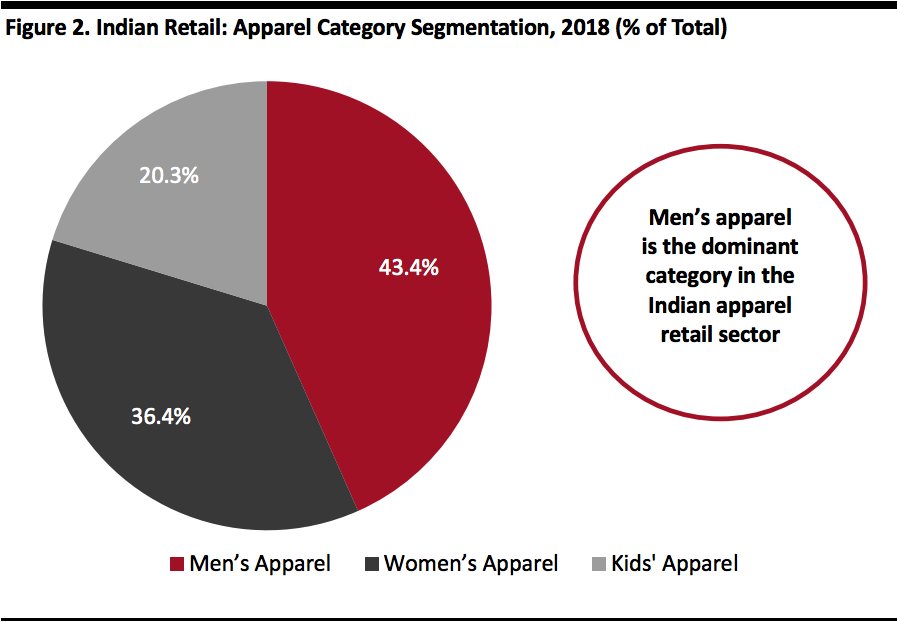

Fiscal years ended March 31; data converted to US dollars at constant 2020 exchange ratesSource: MOSPI/Coresight Research[/caption] Four Characteristics of the Indian Apparel Market There are four characteristics unique to India that have shaped the country’s clothing market and its consumers’ fashion preferences: 1. India’s apparel market is fragmented. A few large, prominent names and numerous smaller, independent retailers make up the nation’s apparel market. Organized, modern retail accounts for only around 10% of India’s total retail market, according to IBEF estimates, its share of the clothing sector is much higher, comprising approximately 35% of total sales in 2016, according to the latest data from management consulting firm McKinsey. This share is expected to grow to 45% by 2025, according to McKinsey’s estimates. 2. Indian consumers are loyal to traditional dress. India comprises 28 states and nine union territories, almost all of which have a distinct identity exhibited through language, spiritual beliefs and traditional dress. The ethnic-wear market in India is worth around $17.2 billion and accounts for some 32% of the nation’s total apparel market, according to recent data from retail intelligence portal Indiaretailing.com—and this share is expected to grow. The ethnic-wear segment comprises men’s, women’s, boys’ and girls’ clothing. 3. The Indian clothing market is led by menswear. India is among a minority of large economies in the world where menswear dominates the apparel market. According to Statista’s estimates for 2018, men’s apparel generated revenues that accounted for 43.4% of the total value of the industry; women’s apparel, on the other hand, represented 36.4% (see Figure 2). [caption id="attachment_108934" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Source: Marketline[/caption]

However, the womenswear apparel market in India is growing at a CAGR of 11%, driven by a significant shift toward branded apparel. It is therefore poised to beat the men’s apparel segment in size by 2025, according to business news website Livemint.

In Western markets such as the UK and the US, roughly half of all clothing sales are in the womenswear segment.

4. Many of the larger players are owned by conglomerates. Most of the large homegrown retailers in India belong to conglomerates. One exception is Future Lifestyle Fashions, which began as a retail pure play.

Despite Indians’ diverse cultures and loyalty to traditional dress, international brands have found an audience in the country’s youthful and evolving consumers. A relaxation in economic policy has significantly helped international brands enter and sell in India more easily.

Source: Marketline[/caption]

However, the womenswear apparel market in India is growing at a CAGR of 11%, driven by a significant shift toward branded apparel. It is therefore poised to beat the men’s apparel segment in size by 2025, according to business news website Livemint.

In Western markets such as the UK and the US, roughly half of all clothing sales are in the womenswear segment.

4. Many of the larger players are owned by conglomerates. Most of the large homegrown retailers in India belong to conglomerates. One exception is Future Lifestyle Fashions, which began as a retail pure play.

Despite Indians’ diverse cultures and loyalty to traditional dress, international brands have found an audience in the country’s youthful and evolving consumers. A relaxation in economic policy has significantly helped international brands enter and sell in India more easily.

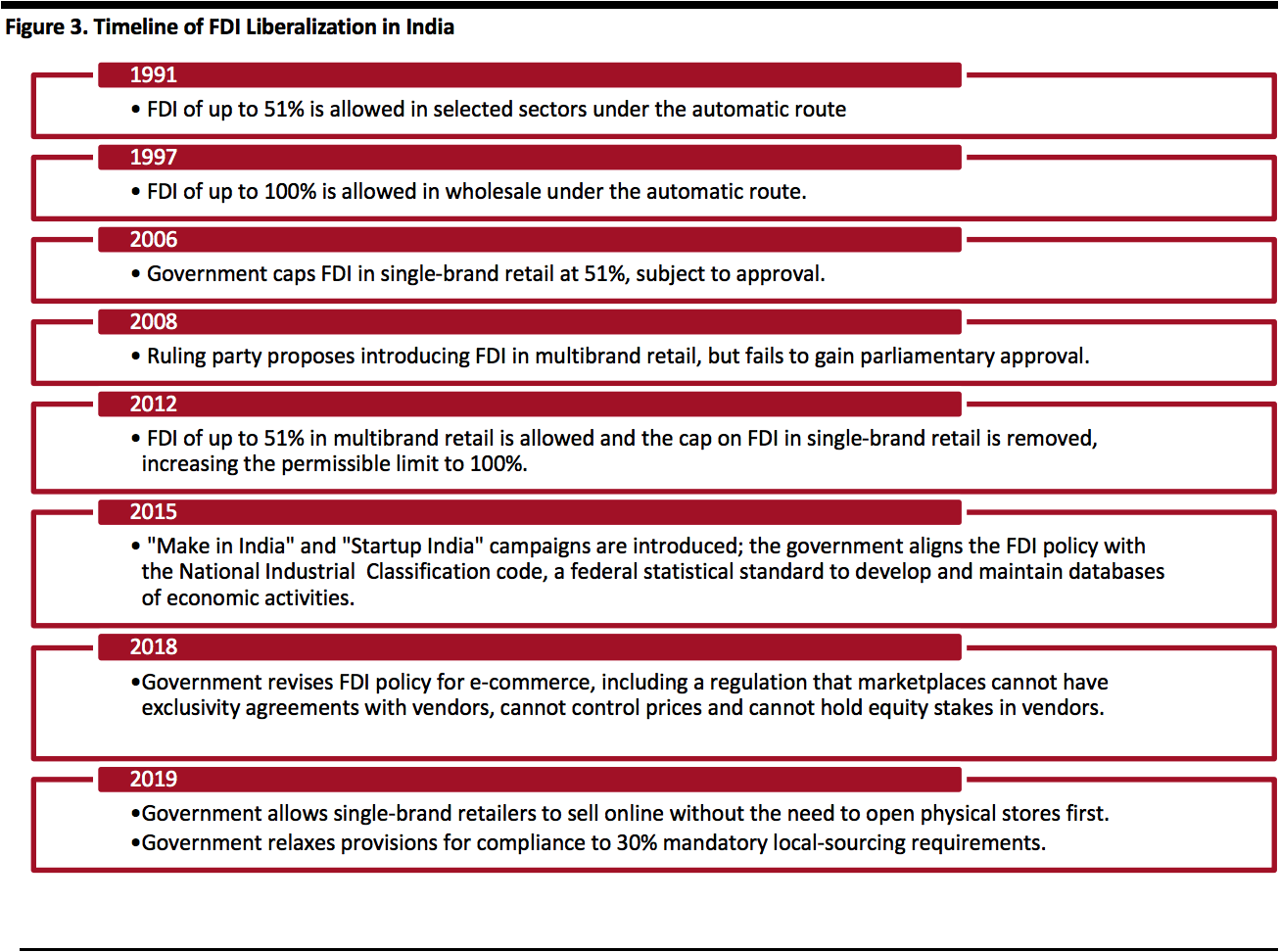

Economic Reforms Enable International Firms To Enter India

Between 1990 and 2004, the Indian economy was somewhat liberal, and the government considered foreign investments on a case-by-case basis. After 2004, the government slowly moved toward a more protectionist stance, making it challenging for foreign firms to establish businesses in India and sell directly to the domestic market. As one of its first moves to open up the economy, the Indian government implemented a policy in 2006 that allowed FDI of up to 51% in single-brand retail, subject to government approval. This meant that retailers such as Gap and Zara, which sold only their own-brand products, were allowed to open stores in India in partnership with a local company, with a maximum ownership stake of 51%. In 2012, the government removed this threshold and increased the permissible investment by a foreign entity in single-brand retail to 100%. Swedish fast-fashion retailer H&M became the first foreign apparel retailer to enter India independently through this route. In addition to removing the cap on single-brand retail investment in 2012, the government allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail (which includes department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands), subject to government approval. In 2018, the government revised its FDI policy for e-commerce, including a regulation that marketplaces cannot have exclusivity agreements with vendors, cannot control prices and cannot hold equity stakes in vendors. E-commerce marketplaces were given one month to comply and are now required to submit certificates annually stating their compliance. In August 2019, the government began allowing single-brand retailers to launch e-commerce operations without the need to establish a brick-and-mortar presence, which had previously been required. The government also relaxed provisions for compliance to 30% mandatory local-sourcing requirements. In Figure 3, we outline some of the major milestones that mark the liberalization of India’s economy. [caption id="attachment_108935" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: TechSci Research/IBEF[/caption]

As a result of these liberalization measures, many international brands have now entered the Indian market through various routes.

Entry Routes for Foreign Brands and Retailers in India

With restrictions on incorporating foreign companies in India, the government has established several routes through which international firms can trade in the country.

Under the non-FDI route, there are two methods through which international retailers can sell goods in India:

Source: TechSci Research/IBEF[/caption]

As a result of these liberalization measures, many international brands have now entered the Indian market through various routes.

Entry Routes for Foreign Brands and Retailers in India

With restrictions on incorporating foreign companies in India, the government has established several routes through which international firms can trade in the country.

Under the non-FDI route, there are two methods through which international retailers can sell goods in India:

- Licensing—Under this method, the owner of the brand (the licensor) leases the rights to use the brand name to the retailer (the licensee), allowing the latter to stock and sell branded merchandise. For example, the Lee Cooper brand, which belongs to the Iconix Brand Group (the licensor), is licensed to Future Lifestyle Fashions (the licensee) in India. PVH Corp. licenses the Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger brands to Arvind Brands in India.

- Franchising—Similar to licensing, franchising allows a retailer (the franchisee) to use a brand’s (franchisor’s) intellectual property, as well as its business model, marketing strategy and distribution model, in order to sell the brand’s goods. In India, Arvind Brands owns the rights to sell merchandise belonging to American fast-fashion brand Forever 21 online and offline through a franchise agreement. Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy in the US in September 2019, but stores in India remain operational.

- JV—A JV is an enterprise in which two or more firms have pooled their capital and other resources. One of the most famous examples of an international retailer entering India through this route is British retailer M&S’s JV with Reliance Retail, part of Reliance Industries. M&S owns 51% of the JV, incorporated as Marks & Spencer Reliance India, while Reliance Retail owns the remainder.

- Wholly owned subsidiary—With this method, an organization (the parent or holding company) sets up a new company that is incorporated as a domestic business in India. The entire equity stake of the subsidiary is owned by the parent company. H&M was one of the first international retailers to enter India after the cap on FDI in single-brand retail was removed. The company created a wholly owned subsidiary called H&M Hennes & Mauritz Retail.

- Limited-liability partnership—In this model, the partners of the firm have limited liabilities, i.e., one partner cannot be held responsible for another partner’s mismanagement of the company.

- Extension of the foreign entity via a liaison office, branch office or project office—International companies can also set up an office in India that represents their interests under one of the above categories. The establishment of a liaison office, branch office or project office is subject to further rules laid out by the Indian government and central bank.

Key International Brands in Indian Apparel Retail and Their Local Partners

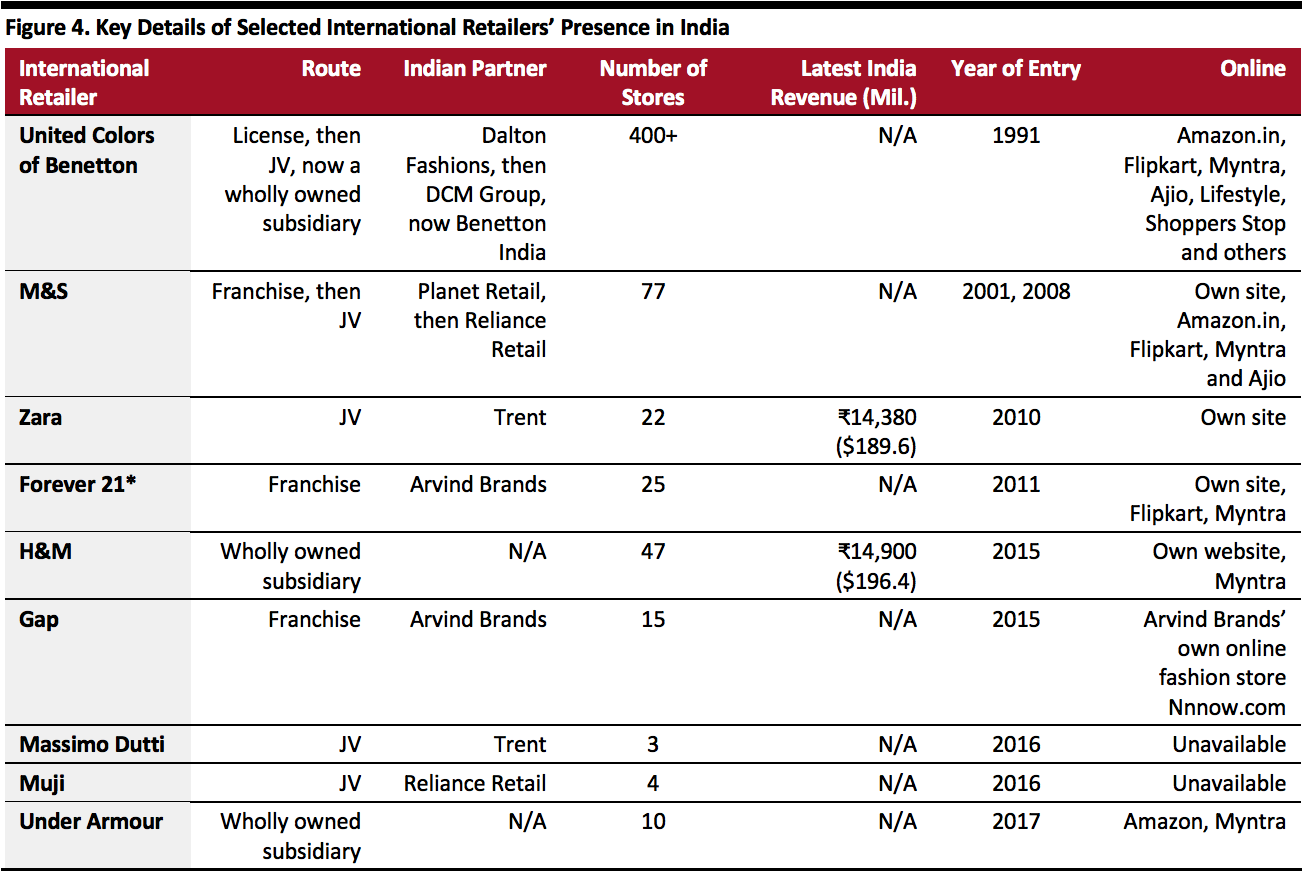

In this section, we discuss some of the major international apparel brands operating in India and the retailers that they have partnered with in order to sell in the country. Although fast fashion is a fairly new concept in India, it is quickly gaining traction, and brands such as H&M and Zara have found a lot of favor among Indian consumers. In fact, when H&M opened its first store in India, at the Select Citywalk Mall in New Delhi, the mall remained open all night before the opening to accommodate the enthusiastic shoppers and fans of the Swedish retailer who lined up to be the first to buy its clothes. [caption id="attachment_108936" align="aligncenter" width="700"] *Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy in the US in September 2019, but stores in India remain operational

*Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy in the US in September 2019, but stores in India remain operational Source: Company reports/The Economic Times/Livemint.com/IndianRetailer.com/Retail4Growth.com[/caption]

Gap Inc. struggled in 2015, its first year of trading in India, as its clothing sizes were not tailored to the Indian market and its price points were much higher than those of Zara, for example, due to its sourcing policy: The retailer imported its products into India, transferring transport and tariff costs to the customer, unlike Zara, H&M and M&S, all of which source the majority of their products locally. Newspapers reported in February 2017 that, in order to boost its growth in India, Gap Inc. initiated a process to slash its prices by some 10–15% by altering its sourcing policy to produce 30–40% of merchandise in India.

Gap Inc. struggled in 2015, its first year of trading in India, as its clothing sizes were not tailored to the Indian market and its price points were much higher than those of Zara, for example, due to its sourcing policy: The retailer imported its products into India, transferring transport and tariff costs to the customer, unlike Zara, H&M and M&S, all of which source the majority of their products locally. Newspapers reported in February 2017 that, in order to boost its growth in India, Gap Inc. initiated a process to slash its prices by some 10–15% by altering its sourcing policy to produce 30–40% of merchandise in India.

Under Armour debuted in India through an exclusive partnership with Amazon in March 2017. It subsequently incorporated its wholly owned subsidiary Under Armour India in October 2018 and then went on to open its first store in DLF Promenade Mall in March 2019. At the end of 2019, the retailer operated 10 stores in India across Bengaluru, Chennai, Gurgaon, Guwahati, Noida, Pune and Surat. The company announced plans to open 15 new stores in 2020 to end the year with a fleet of 25 stores in India, but it remains to be seen whether Under Armour can follow through with this plan given the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the retail landscape in the country.

Others

Rising real-estate prices and complicated entry regulations have led many brands to resort to the licensing and franchising routes, and we can expect to see more brands choosing to enter the Indian market with these models instead of through the more tedious JV model. These routes have also been facilitated by the rise in e-commerce in India, with banners such as Dorothy Perkins and Miss Selfridge are serving customers in the country through fashion website Myntra. Dorothy Perkins is reportedly considering opening physical stores in India.

Some other international brands that made their debut in India in 2019 include Japanese casual-wear manufacturer and retailer Uniqlo, Italian denim and smart casual-wear brand Replay, global sports brand Trusax, Thailand-based fashion accessories brand Lyn and American lingerie brand Parfait.

According to McKinsey’s 2019 “FashionScope” report, over 300 international brands are expected to launch stores in India by 2021.

Under Armour debuted in India through an exclusive partnership with Amazon in March 2017. It subsequently incorporated its wholly owned subsidiary Under Armour India in October 2018 and then went on to open its first store in DLF Promenade Mall in March 2019. At the end of 2019, the retailer operated 10 stores in India across Bengaluru, Chennai, Gurgaon, Guwahati, Noida, Pune and Surat. The company announced plans to open 15 new stores in 2020 to end the year with a fleet of 25 stores in India, but it remains to be seen whether Under Armour can follow through with this plan given the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the retail landscape in the country.

Others

Rising real-estate prices and complicated entry regulations have led many brands to resort to the licensing and franchising routes, and we can expect to see more brands choosing to enter the Indian market with these models instead of through the more tedious JV model. These routes have also been facilitated by the rise in e-commerce in India, with banners such as Dorothy Perkins and Miss Selfridge are serving customers in the country through fashion website Myntra. Dorothy Perkins is reportedly considering opening physical stores in India.

Some other international brands that made their debut in India in 2019 include Japanese casual-wear manufacturer and retailer Uniqlo, Italian denim and smart casual-wear brand Replay, global sports brand Trusax, Thailand-based fashion accessories brand Lyn and American lingerie brand Parfait.

According to McKinsey’s 2019 “FashionScope” report, over 300 international brands are expected to launch stores in India by 2021.

Socioeconomic Factors that Make India an Attractive Destination for International Retailers

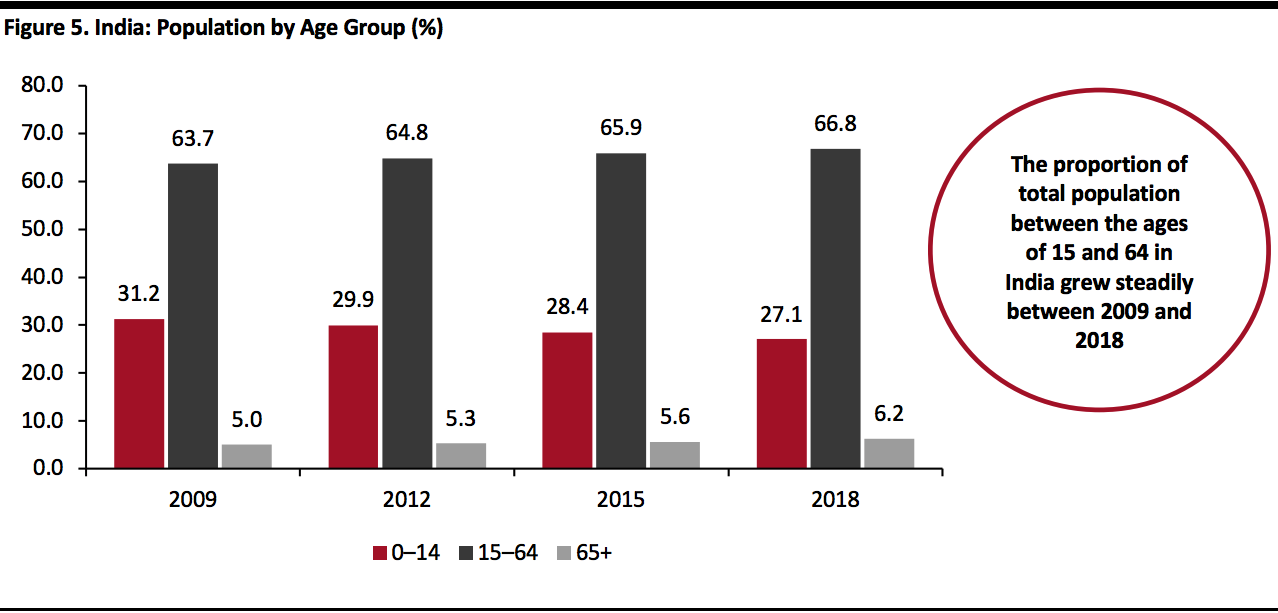

There are many factors that make India a sought-after market for foreign retailers. Western apparel retailers have seen declining demand on their home turf in recent years, due to the highly competitive, low-growth nature of many developed markets. So, they have been looking eastward for opportunities in emerging markets that are poised for growth. We outline some of India’s unique socioeconomic factors that make it a popular high-growth target destination for many international retailers. A Large, Youthful Population in Tune with Global Trends India’s population is young. Some 67% of the country’s 1.3 billion people were between the ages of 15 and 64 in 2018, according to World Bank estimates, and a significant proportion of that group was below the age of 35. There is a growing preference for international brands and Western apparel among this age group, which is becoming increasingly globally connected through social media platforms. [caption id="attachment_108949" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Statista/World Bank[/caption]

Population Migration from Rural to Urban Areas

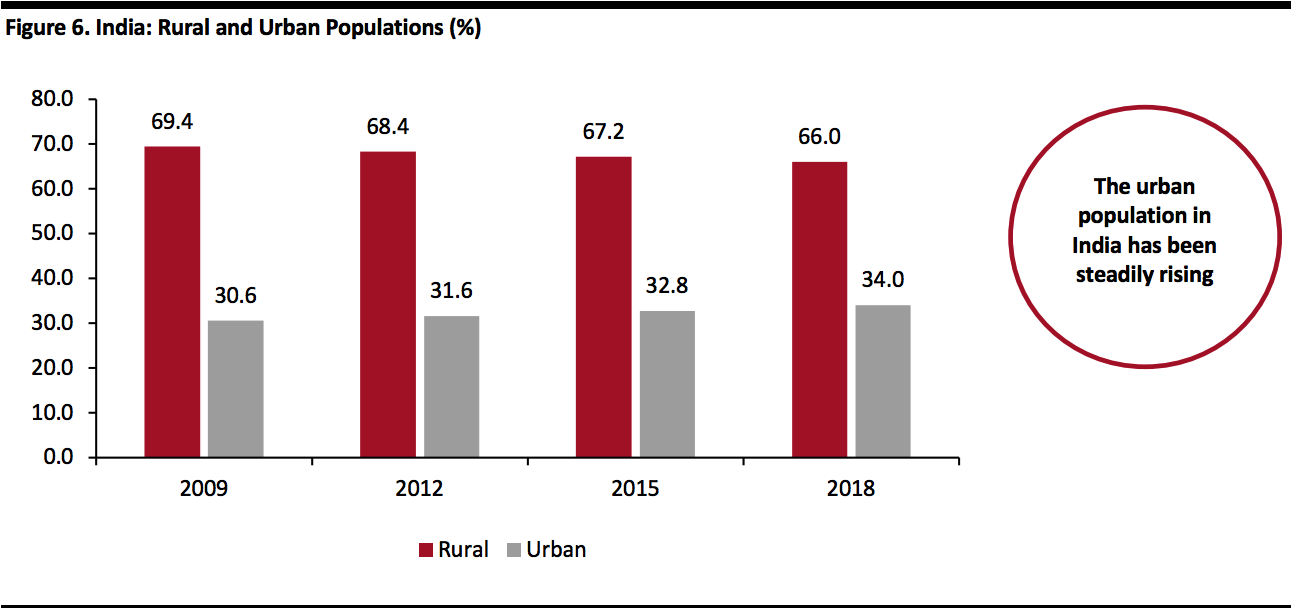

Some 66% of residents in India lived in rural parts of the country in 2018, according to the World Bank, but the urban population has been expanding faster in the last decade than it did in previous decades. This has led to broader knowledge and acceptance of other cultures, both within the country and outside it, a less conservative social mindset and more consumers aspiring to modern lifestyles.

[caption id="attachment_108951" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

Source: Statista/World Bank[/caption]

Population Migration from Rural to Urban Areas

Some 66% of residents in India lived in rural parts of the country in 2018, according to the World Bank, but the urban population has been expanding faster in the last decade than it did in previous decades. This has led to broader knowledge and acceptance of other cultures, both within the country and outside it, a less conservative social mindset and more consumers aspiring to modern lifestyles.

[caption id="attachment_108951" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: World Bank[/caption]

Significant Growth in GDP per Capita

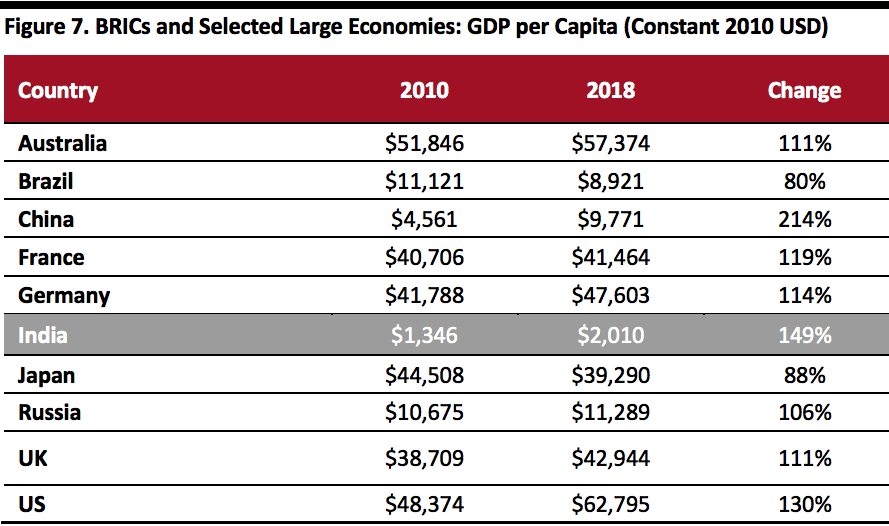

In absolute-value terms, GDP per capita in India is one of the lowest among both the BRIC countries and the largest global economies, which is indicative of a lower standard of living. However, India showed the second-strongest growth in GDP per capita among selected countries between 2010 and 2018, after China.

[caption id="attachment_108952" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Source: World Bank[/caption]

Significant Growth in GDP per Capita

In absolute-value terms, GDP per capita in India is one of the lowest among both the BRIC countries and the largest global economies, which is indicative of a lower standard of living. However, India showed the second-strongest growth in GDP per capita among selected countries between 2010 and 2018, after China.

[caption id="attachment_108952" align="aligncenter" width="580"] Source: World Bank[/caption]

Proximity to Source, as India Is a Textile Manufacturing Hub

India is also appealing to international retailers because it is a textile and apparel manufacturing hub that provides a faster and more economical route to the source of production. India is the largest cotton and jute producer in the world and is the third-largest exporter of textiles and apparel. The nation accounted for 5% of world trade in textiles and apparel in 2017, according to the IBEF.

Many of the international brands operating in India already source products from the country to sell in their stores across the globe. Shipping and distribution account for a significant proportion of the cost of goods, but retailers that source locally in India save on those costs while selling to the domestic market.

Under the “Make in India” initiative launched in 2014, the government provides several incentives for textile and apparel manufacturers in India. The government has also established Special Economic Zones and National Investment and Manufacturing Zones, where manufacturers can set up production facilities at subsidized rates. Furthermore, the government has approved a skill-development initiative called Scheme for Capacity Building in Textile Sector with a budget of $202.9 million for a three-year period between 2017 and 2020.

Source: World Bank[/caption]

Proximity to Source, as India Is a Textile Manufacturing Hub

India is also appealing to international retailers because it is a textile and apparel manufacturing hub that provides a faster and more economical route to the source of production. India is the largest cotton and jute producer in the world and is the third-largest exporter of textiles and apparel. The nation accounted for 5% of world trade in textiles and apparel in 2017, according to the IBEF.

Many of the international brands operating in India already source products from the country to sell in their stores across the globe. Shipping and distribution account for a significant proportion of the cost of goods, but retailers that source locally in India save on those costs while selling to the domestic market.

Under the “Make in India” initiative launched in 2014, the government provides several incentives for textile and apparel manufacturers in India. The government has also established Special Economic Zones and National Investment and Manufacturing Zones, where manufacturers can set up production facilities at subsidized rates. Furthermore, the government has approved a skill-development initiative called Scheme for Capacity Building in Textile Sector with a budget of $202.9 million for a three-year period between 2017 and 2020.

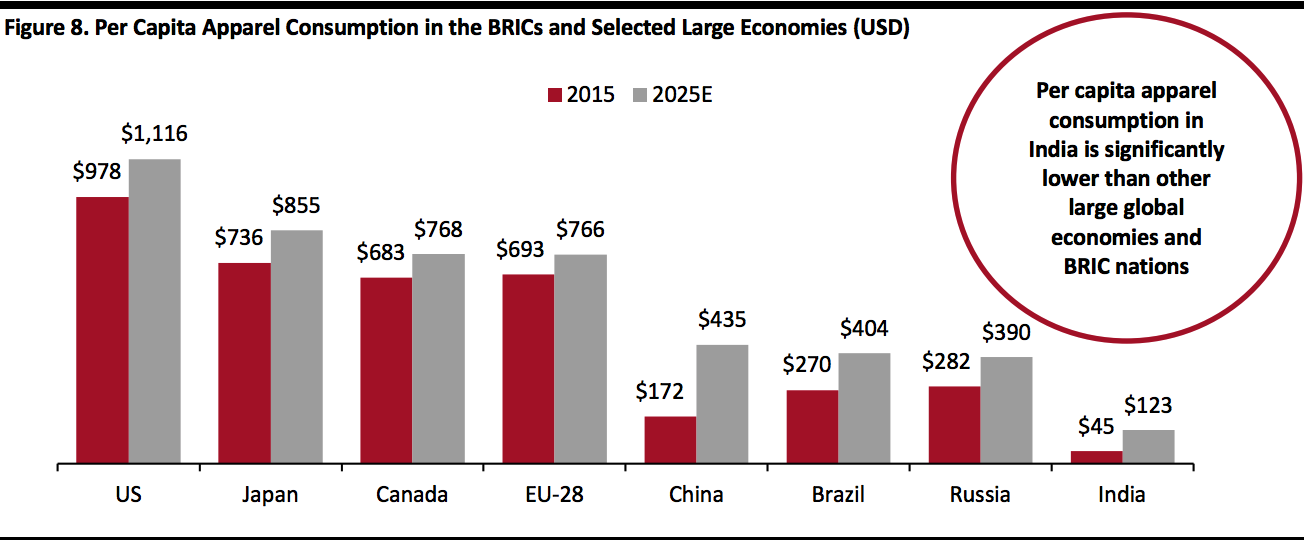

Five Remaining Challenges That International Retailers Face

While India is on a strong growth trajectory and has many socioeconomic features and policies that are favorable to foreign retailers entering the market, a number of challenges still exist. International retailers that wish to operate in India must still meet FDI requirements and deal with low apparel consumption rates, a lack of infrastructure, a potential loss of autonomy over business decision-making and cultural factors that are unique to the country. 1. FDI Regime Comes with Conditions Despite the relaxation in regulations regarding investment in, and ownership of, international brands’ operations, the Indian government has levied many conditions that make entry into India a difficult process for retailers. For single-brand retail, FDI of 100% is allowed, but if the foreign investment exceeds 51% of the total, the retailer is required to source 30% of its merchandise from Indian vendors, preferably from medium-sized and small enterprises, unless the retailer requires state-of-the-art technology unavailable in the country. In August 2019, the government also relaxed provisions for compliance to 30% mandatory local-sourcing requirements. For multibrand retail, the permissible limit for foreign investment is 51% of the total capital, and the minimum investment amount is $100 million. At least 50% of the first tranche of $100 million should be invested in back-office infrastructure over three years and should cover manufacturing, quality control, warehousing, distribution and logistics. Additionally, at least 30% of merchandise sold in India should be procured from within the country, preferably from medium-sized and small enterprises whose startup capital does not exceed $2 million. 2. Per-Capita Apparel Consumption Is Still Low in India Compared with the other BRIC nations and some of the largest global economies, per-capita apparel consumption is still very low in India. Indian retail consultancy Wazir Advisors estimates that apparel consumption per capita in India will increase from $45 in 2015 to $123 in 2025. That means it will still be lower in 2025 than it was in 2015 in the other BRIC nations and many of the world’s large developed economies, as illustrated in Figure 8. As per Wazir Advisors’ latest estimates, apparel consumption per capita increased to $51 in 2018. [caption id="attachment_108953" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Source: Wazir Advisors[/caption]

3. Lack of Infrastructure

Despite the size and economic growth of India, mall and modern store penetration is still low in the country. In comparison to developed economies, organized apparel retail as a share of total apparel retail is considerably lower in India (35%).

Logistics and distribution channels in India are inefficient, and the country has a long way to go in terms of improving its transport networks (including roads, ports, railways and airports), power supply and warehouse facilities. This has resulted in underdeveloped supply chains, which means higher logistics costs for retailers in the country. According to real-estate consulting firm Knight Frank, India’s logistics costs account for 13–17% of the country’s GDP which is almost double the logistics cost-to-GDP ratio of developed economies (6–9%), such as France, Hong Kong and the US.

There is also a lack of large-format retail infrastructure in India that most international brands are used to in Europe and the US. For example, the first Massimo Dutti store opened in India measures about 5,000 square feet, and its second store is 5,000–6,000 square feet. Both stores are much smaller than the retailer’s average global store, which is 8,000–10,000 square feet. Other international retailers entering India will need to adapt their design and layout to accommodate the country’s smaller store spaces.

4. Loss of Autonomy over Operations

The FDI policy for international multibrand retailers forces them to partner with an Indian retailer, which means that the international companies are likely to lose some autonomy in terms of decision-making and control over their business in India. Foreign retailers may also need to share some expertise and best practices with local partners in order to gain a competitive advantage over domestic retailers.

5. Culture

Although India is rapidly modernizing, and its consumers are increasingly open to new fashion trends, many Indians tend to be quite conservative compared with their global peers. International retailers may therefore need to provide a more conservative and carefully chosen assortment to attract shoppers in India than they would when selling elsewhere in the world.

Source: Wazir Advisors[/caption]

3. Lack of Infrastructure

Despite the size and economic growth of India, mall and modern store penetration is still low in the country. In comparison to developed economies, organized apparel retail as a share of total apparel retail is considerably lower in India (35%).

Logistics and distribution channels in India are inefficient, and the country has a long way to go in terms of improving its transport networks (including roads, ports, railways and airports), power supply and warehouse facilities. This has resulted in underdeveloped supply chains, which means higher logistics costs for retailers in the country. According to real-estate consulting firm Knight Frank, India’s logistics costs account for 13–17% of the country’s GDP which is almost double the logistics cost-to-GDP ratio of developed economies (6–9%), such as France, Hong Kong and the US.

There is also a lack of large-format retail infrastructure in India that most international brands are used to in Europe and the US. For example, the first Massimo Dutti store opened in India measures about 5,000 square feet, and its second store is 5,000–6,000 square feet. Both stores are much smaller than the retailer’s average global store, which is 8,000–10,000 square feet. Other international retailers entering India will need to adapt their design and layout to accommodate the country’s smaller store spaces.

4. Loss of Autonomy over Operations

The FDI policy for international multibrand retailers forces them to partner with an Indian retailer, which means that the international companies are likely to lose some autonomy in terms of decision-making and control over their business in India. Foreign retailers may also need to share some expertise and best practices with local partners in order to gain a competitive advantage over domestic retailers.

5. Culture

Although India is rapidly modernizing, and its consumers are increasingly open to new fashion trends, many Indians tend to be quite conservative compared with their global peers. International retailers may therefore need to provide a more conservative and carefully chosen assortment to attract shoppers in India than they would when selling elsewhere in the world.