EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

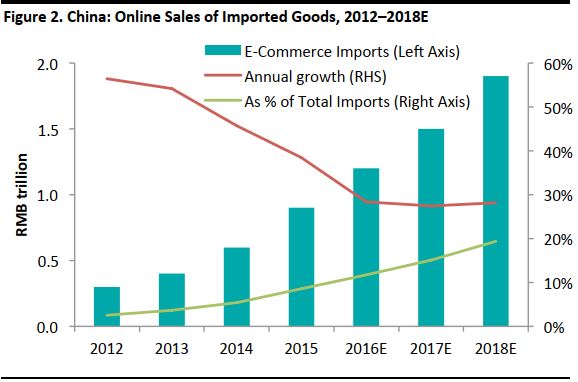

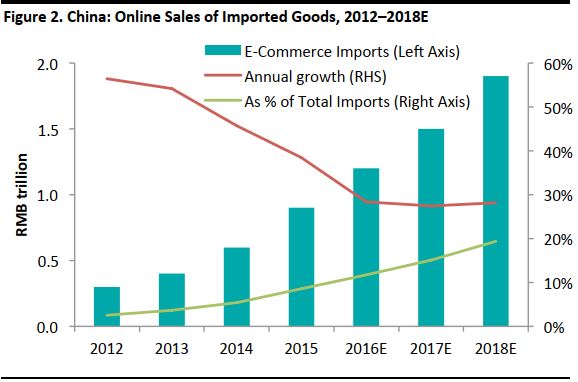

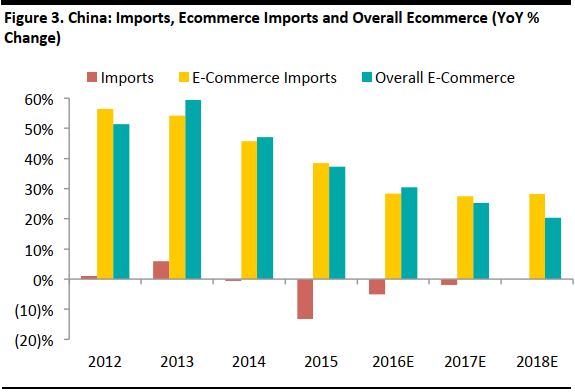

China’s cross-border ecommerce (CBEC) imports, which refer to the purchase of overseas products online, are expected to increase to ¥1.9 trillion (US$285 billion) in 2018, from ¥0.9 trillion (US$136 billion) in 2015, according to iResearch.

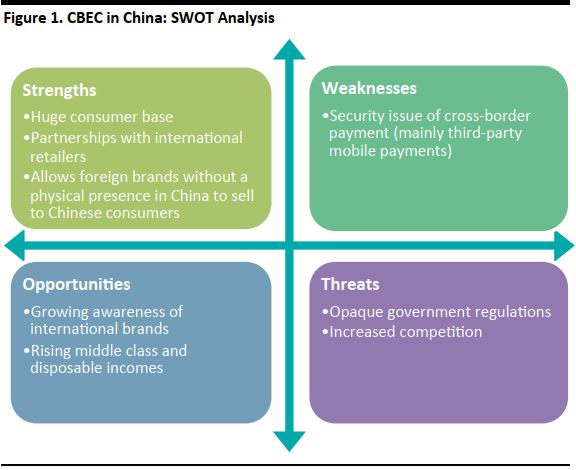

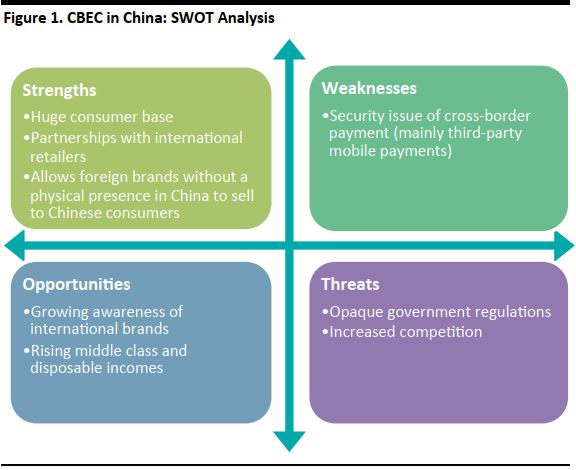

Rising disposable incomes, more sophisticated consumer preference and growing awareness of international brands have caused Chinese shoppers to seek out imported goods. From a regulatory perspective, the Chinese authorities have implemented rules to reduce the friction of cross-border online purchases and combat fraud, which has created an environment conducive to purchasing imported products online.

In addition, luxury goods typically sell at a premium in China compared with overseas, due to import duties. Our study of pricing differences across major import channels (CBEC and physical stores) indicate that CBEC import platforms are one of the most cost-effective ways of purchasing overseas products, without the concerns of authenticity and reliability of daigou, i.e., buying overseas goods through individual agents.

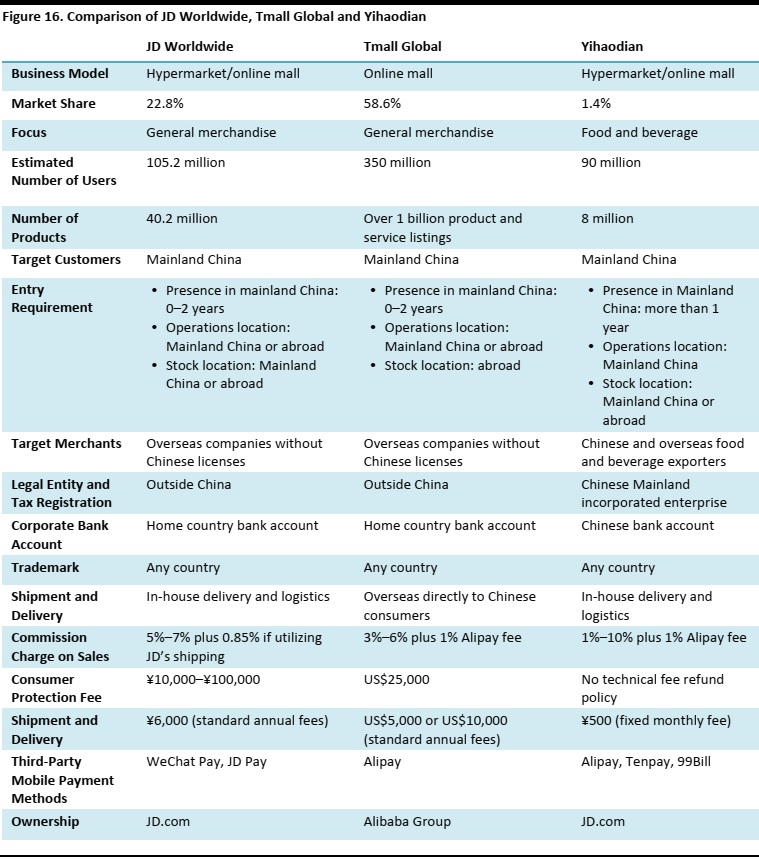

In order to succeed in the Chinese market, international retailers are advised to have a strategic plan for CBEC which complements their existing China strategy. International retailers will need to decide which cross-border channels to sell on, driven by considerations of each platform’s targeted clientele and product category, costs, track record and suite of value-added services. Two relatively popular options include selling wholesale to an ecommerce direct sales distributor (or self-operated platform) or working with one of the established CBEC marketplaces, with the two largest being Tmall Global and JD Worldwide.

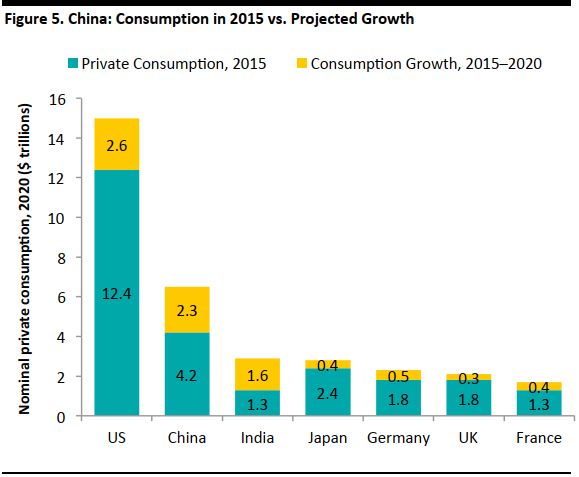

Source: Shutterstock

CBEC IN CHINA: THE NEXT FRONTIER IN ONLINE PURCHASES

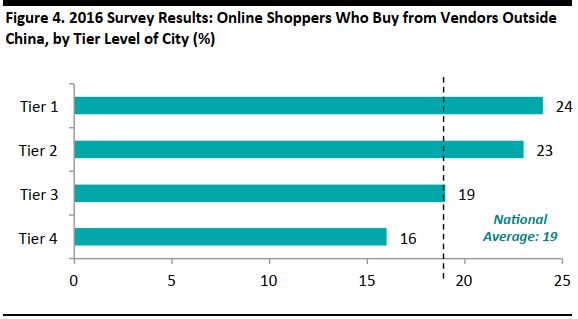

Cross-border ecommerce (CBEC) has grown rapidly and will likely drive the next leg of ecommerce growth in China. According to the Boston Consulting Group, a quarter of China’s population will shop either directly on foreign sites or through third parties in 2020, up from 15% in 2016. Higher prices of luxury goods in China, rising standards of living and greater exposure to foreign products will all help drive the trend. For international merchants, even those that have no physical presence in China, the rise of CBEC presents a huge opportunity to reach the Chinese consumer base.

DEFINING CBEC

CBEC is electronic foreign trade by which products are displayed and transactions are conducted via the Internet. Buyers and sellers in different countries transact online and the goods are delivered through cross-border logistics.

Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

CURRENT MARKET SIZE OF CHINA’S CBEC INDUSTRY

China’s CBEC imports reached ¥907 billion (US$136 billion) in 2015 and are expected to reach ¥1.9 trillion (US$285 billion) in 2018, according to iResearch. As a percentage of the country’s total imports, ecommerce imports are expected to increase from 9% in 2015 to 19% by 2018. The majority of this growth will be driven by Chinese shoppers’ appetite for foreign brands.

A joint report from Accenture and AliResearch predicts that the transaction volume of imported goods purchased online in China will reach US$245 billion by 2020, making the country the largest cross-border business-to-consumer market in the world.

Source: iResearch/Fung Global Retail & Technology

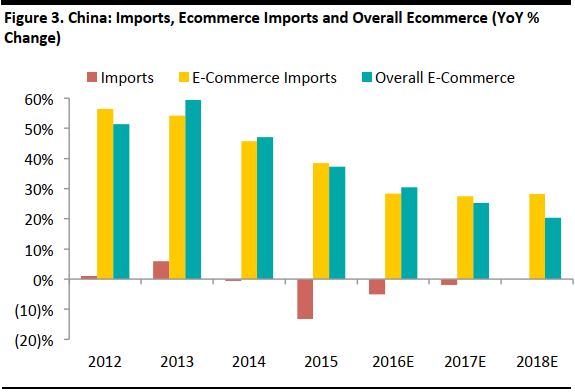

CBEC volumes grew by 39% in 2015, despite a 13% decline in physical imports over the same period.

Source: China Customs/iResearch

FACTORS DRIVING THE INCREASE IN CBEC IN CHINA

There are several factors responsible for the rise of CBEC in China, including changing demographics, changing consumer preferences, changing regulations, and price differences between China and other markets.

Changing Demographics

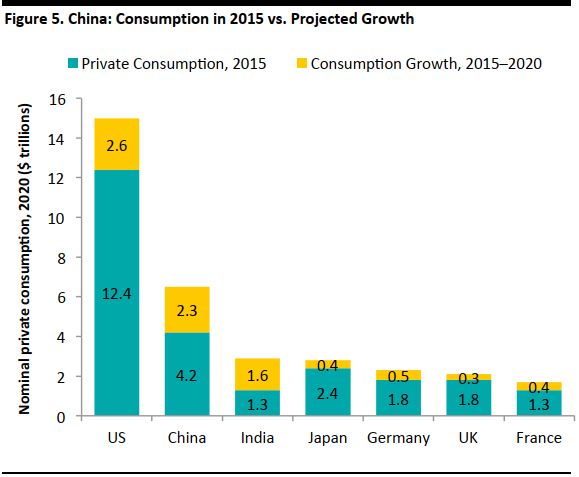

The continued rise of the upper middle class in China and increasing disposable incomes will drive the country’s standard of living higher. The Boston Consulting Group expects that, by 2020, 81% of consumption growth will come from households whose annual income is more than US$24,000.

China’s population has become more sophisticated and tech savvy, and the country now has the most Internet users of any country in the world. It has also become the world’s largest ecommerce market. Online retail sales in China totaled approximately US$630 billion in 2015, making the market nearly 80% larger than the US retail ecommerce market.

Changing Consumer Preferences

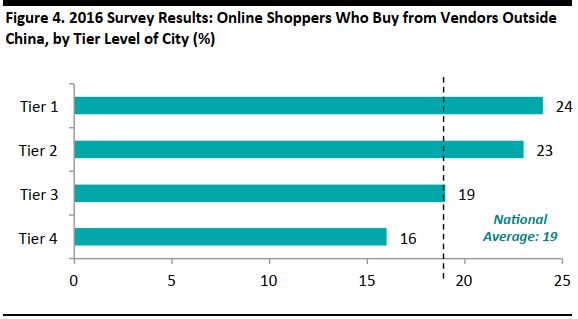

Many Chinese consumers aspire to buy international brands or products that are not yet available in China, and many perceive international brands to be of higher quality. Chinese consumers have also become more sensitive to quality products that are designed to contribute to one’s well-being. So, demand for premium goods that enhance a personal sense of well-being—such as organic food and health supplements—is expected to accelerate. According to a 2016 McKinsey & Company survey of Chinese Internet users, nearly one-fifth of digital consumers buy some goods from vendors outside China, and they prefer to buy items that are either expensive or difficult to get from domestic vendors.

Source: Shutterstock

Changing Regulations

Chinese authorities have implemented rules that both reduce the friction of cross-border online purchases and combat fraud. Consequently, consumers now feel more protected from counterfeit products than they did before. The authorities have moved to reduce illegal gray-market imports by introducing a new import duty regime, establishing trade zones and expediting customs clearance of goods purchased via CBEC.

Price Differences Between China and Overseas Markets

High-end luxury goods are priced higher in China than they are in other markets, as they are subject to significant Chinese import duties and taxes. Given the price differences, it is unsurprising that more than 60% of Chinese consumers bought luxury products abroad in 2015, according to the Fortune Character Group; these included handbags, cosmetics and mobile gadgets.

Source: Shutterstock

- Lower prices are the main reason Chinese consumers buy luxury items from overseas. According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, the average price of wine and spirits in China is 64% higher than overseas and can reach an 85% premium. The average price of watches in China is 33% higher than overseas and can reach an

83% premium. The average premium of other luxury items that are popular among Chinese consumers, such as clothing, handbags, cosmetics and shoes, is below 30%.

- The average price differential between luxury goods bought onshore in China and those bought overseas is estimated by the Fortune Character Group to have declined from a peak of 80% five years ago to 20%–30% today. However, the group still expects that 95% of international brands will close some of their physical stores in China and accelerate the opening of online stores in 2016.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit/Boston Consulting Group

ADVANTAGES OF CBEC PLATFORMS COMPARED WITH TRADITIONAL IMPORTS

Importing products into China via CBEC provides benefits for both consumers and international retailers. It allows Chinese shoppers to enjoy a diverse range of international products at lower prices than are available through traditional import channels. Also, in contrast to individual purchasing agents, CBEC platforms offer additional benefits to consumers, such as protection for product authenticity and after-sales customer service.

International retailers can enjoy reduced tariffs and lower regulatory requirements through CBEC, and both are particularly appealing to the skincare and cosmetics, vitamin supplement, and fresh food sectors. Even after factoring in the cross-border sales tax that Chinese authorities announced in April 2016, the after-tax prices of many products on cross-border shopping websites are still lower than those offered by traditional retailers and importers, according to eMarketer. The firm expects overall demand for CBEC to remain strong due to the better prices it offers compared with offline retailers and the perceived quality and better variety of goods on offer.

Source: Shutterstock

According to JD Worldwide, the tax rate for CBEC imports is roughly 11.9%, which is lower than the 30%–50% tax rate for regular import channels. Furthermore, some large CBEC platforms have rules to help prevent the sale of counterfeit products and, so, offer international brands some degree of protection. For example, Alibaba will compensate those customers who have unwittingly purchased counterfeit products on its site and will close shops that sell counterfeit goods. Alibaba’s Tmall Global requires vendors to agree to sell only 100% genuine and overseas-sourced products. However, there is still a concern for counterfeit products. Coach has officially shut down its store on Tmall in September 2016, and will only sell in China via its own branded website.

Setting up a CBEC operation also provides an opportunity for brands to test the Chinese market without establishing a physical presence in China. International retailers can benefit by collecting and analyzing data on Chinese customers, which they can then use to inform their Chinese-market strategies.

PURCHASING A LUXURY ITEM THROUGH DIFFERENT AVENUES

Chinese tourists spent US$137 billion in 2015, more than any other group, according to a study of travel expenditure by Visa—and Chinese travelers are projected to nearly double their spending, to US$255 billion, in 2025. Chinese tourists’ propensity to buy abroad is largely due to the attractive overseas retail market—prices overseas remain low compared with the prices of imported goods.

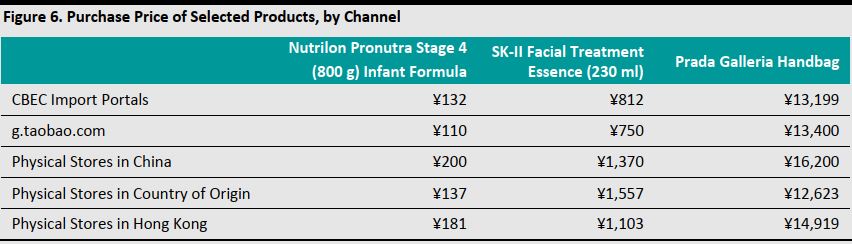

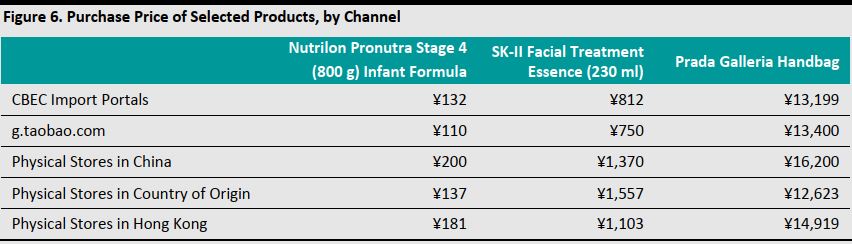

Pricing Study: Prices Under Different Tax Regime and Shopping Channels

We analyzed the pricing differences, by sales channel, of merchandise that is popular among Chinese shoppers. The three product categories we examined were infant milk formula, skincare and luxury handbags. We looked at prices for these items when purchased via the following avenues. For our study, we used the price displayed on each retailer’s website as a proxy for the selling price at its physical stores.

Source: Shutterstock

- Overseas retail store (price as displayed on the retailers’ website)

- Chinese retail store (traditional channel)

- Import ecommerce platform (CBEC channel)

- Daigou (which means “buying on behalf”) websites (B2C and C2C daigou sellers, e.g., taobao.com)

We reached the following conclusions:

- Imported merchandise sold through traditional channels in China is more expensive than merchandise sold through CBEC channels. The primary reason is that imported products have been taxed for import duty, consumption and value-added tax (VAT), whereas some of the CBEC products were covered under preferential tax policies.

- Prices listed on CBEC channels were higher than daigou sellers’ prices on g.taobao.com for infant formula and skincare, but lower for luxury handbags, a difference that we attribute to currency fluctuations.

- Chinese consumers do not base their purchase decisions on price alone. They also consider other factors, such as guarantee of product authenticity, particularly for big-ticket purchases such as luxury items.

Source: g.taobao/JD Worldwide/YHD/Tmall Global/Company websites/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Note: For our study, the price displayed on each retailer’s website is used

as a proxy for the selling price at its physical stores.

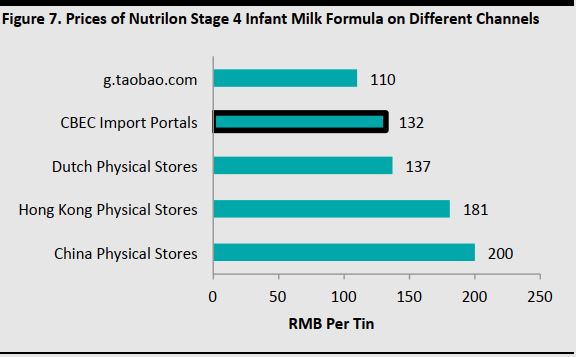

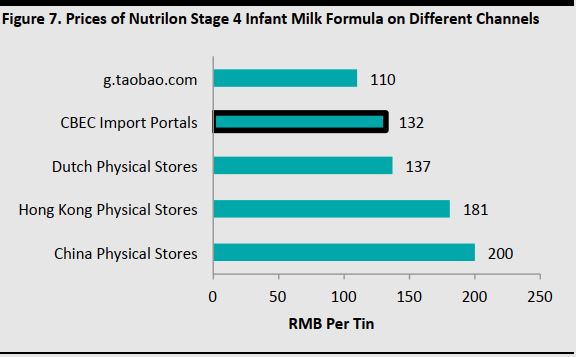

Infant Formula: Nutrilon Pronutra Stage 4 (800 g)

Nutrilon infant formula is priced higher when sold through traditional channels than through CBEC channels. The listed prices are:

- Physical stores

- Mainland Chinese supermarkets: ¥200 per tin. This price includes all traditional tax and duties charged on imported goods.

- Dutch supermarkets (according to their websites): ¥137 per tin.

- Hong Kong supermarkets: ¥181 per tin.

- Major online CBEC platforms: The listed price ranges from ¥125 to ¥139 per tin.

- taobao.com (daigou): ¥110 per tin.

Source:Company websites/Fung Global Retail & Technology

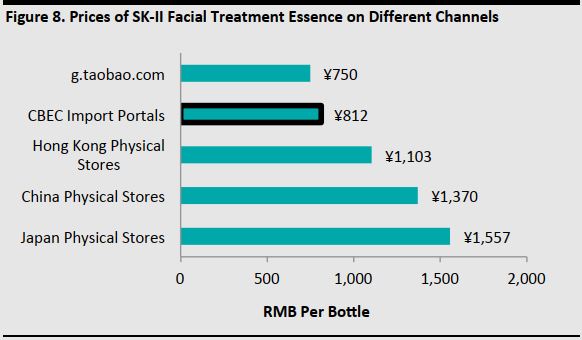

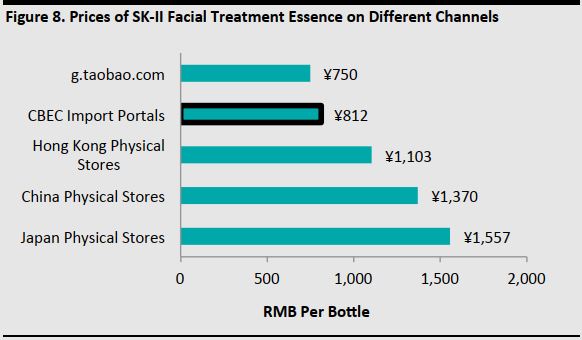

Skincare: SK-II Facial Treatment Essence (230 ml)

Source: Shutterstock

SK-II Facial Treatment Essence sells at the cheapest price on daigou sites, followed by CBEC import portals. The selling price is highest at physical stores. The listed prices are:

- Physical stores

- Mainland Chinese brick-and-mortar stores: ¥1,370 per bottle. This price includes all traditional tax and duties charged on imported goods.

- Japanese stores (according to their websites): ¥1,557 per bottle.

- Hong Kong brick-and-mortar stores: ¥1,103 per bottle.

- Major online CBEC platforms: The listed price ranges from ¥725 to ¥899 per bottle.

- taobao.com (daigou): ¥750 per bottle.

Source: Company websites/Fung Global Retail & Technology

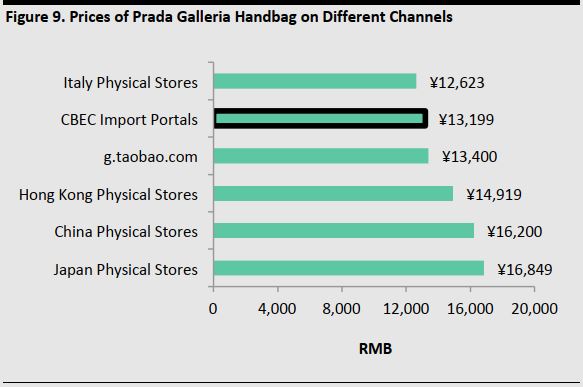

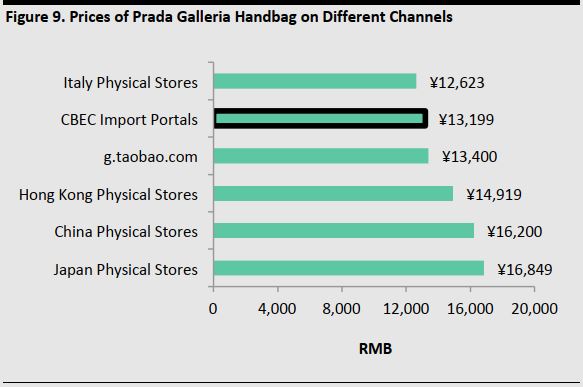

Luxury Handbag: Prada Galleria Handbag

Source: Shutterstock

The Prada Galleria handbag is priced lowest at physical stores in Italy, followed by CBEC import portals, and is the most expensive at physical stores in Japan. The difference in prices is likely impacted by currency movements. The listed prices are:

- Physical stores

- Japanese brick-and-mortar stores: ¥16,849

- Chinese brick-and-mortar stores: ¥ 16,200

- Italian brick-and-mortar stores: ¥ 12,623

- Hong Kong brick-and-mortar stores: ¥14,919

- Major online CBEC platforms: The listed price ranges from ¥12,299 to ¥14,099.

- taobao.com (daigou): ¥13,400.

Source: Company websites/Fung Global Retail & Technology

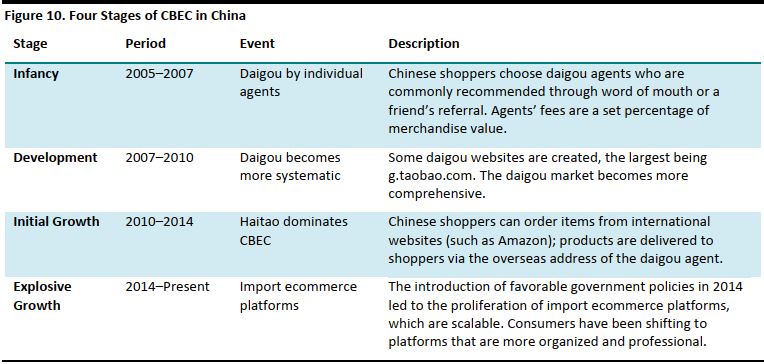

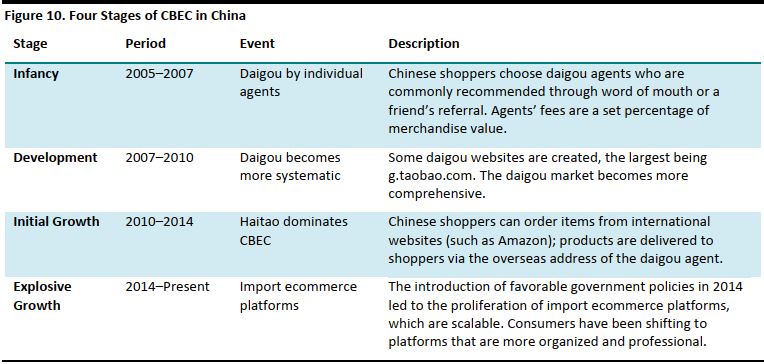

EVOLUTION OF CHINA’S CBEC INDUSTRY

The CBEC industry in China began in 2005 and has gone through four stages:

1. Daigou by Individual Agents (2005–2007)

From 2005 through 2007, CBEC was in its infancy and daigou was a major channel for Chinese shoppers to buy luxury goods that were heavily taxed in China. Daigou (which means “buying on behalf”) enables Chinese shoppers to appoint retail agents to buy merchandise abroad and bring it into the country. Chinese shoppers would take advantage of the lower overseas price, circumvent import duties and get merchandise that was otherwise not available in China. Luxury items purchased through daigou are generally cheaper than they would be if purchased at retail stores in China.

Source: Shutterstock

2. Daigou Becomes More Systematic (2007–2010)

Daigou gained scale as daigou websites were created, offering a one-stop solution to Chinese consumers, allowing them to buy overseas goods with more standardized delivery options. Examples of daigou websites include g.taobao.com, ezbuy, VVcity and OnlyLady.

3. Haitao Dominates CBEC (2010–2014)

Haitao (meaning “buying overseas”) enables Chinese shoppers to order products on overseas ecommerce sites, which are perceived as more reliable and authentic. However, most international ecommerce sites do not offer direct shipping to China, so merchandise has to be shipped through an intermediary shipping company such as 55Haitao.

4. Rise of Import Ecommerce Portals (2014–Present)

This explosive growth stage has been defined by Chinese authorities’ implementation of new CBEC regulations and the opening of import ecommerce portals. With the steady increase in Chinese demand for imported goods, it soon became apparent that overseas ecommerce sites and daigou agents would not be able to satisfy demand, leading the way to more standardized means of purchasing from overseas.

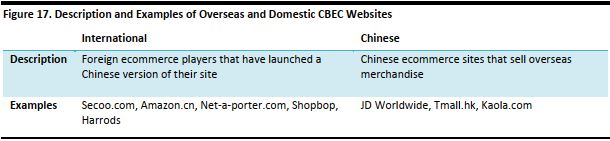

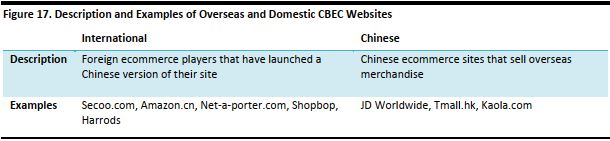

Major foreign ecommerce players have launched Chinese versions of their sites, and major domestic ecommerce companies have launched portals that enable overseas brands to sell directly to Chinese customers; such portals include Alibaba’s Tmall Global (launched in 2014) and JD.com’s JD Worldwide (launched in 2015).

- These CBEC platforms provide post-transaction support, such as returns policies.

- Most of these platforms guarantee products’ quality or authenticity. Some platforms impose strict rules to stamp out counterfeit products and so provide a legitimate overseas online purchasing service.

- Major payment tools, including Alipay and Tencent, have introduced cross-border payment features that work on mobile devices to complement CBEC platforms. The Alipay Cross-Border E-Payment Service allows buyers to pay for goods sold on an international merchant’s website using the renminbi price for checkout. Alipay will remit the sum in a supported foreign currency to the international merchant in settlement and the payment feature includes Customs Declaration Services.

Source: iResearch/Fung Global Retail & Technology

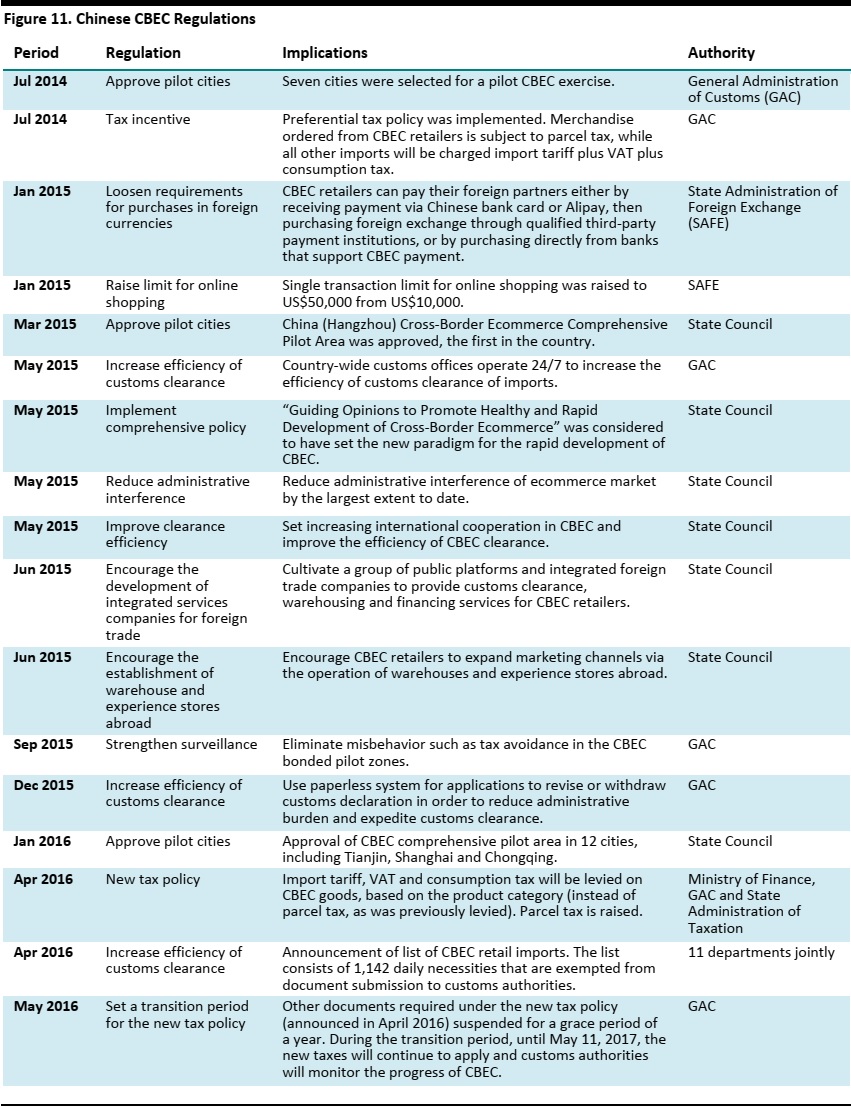

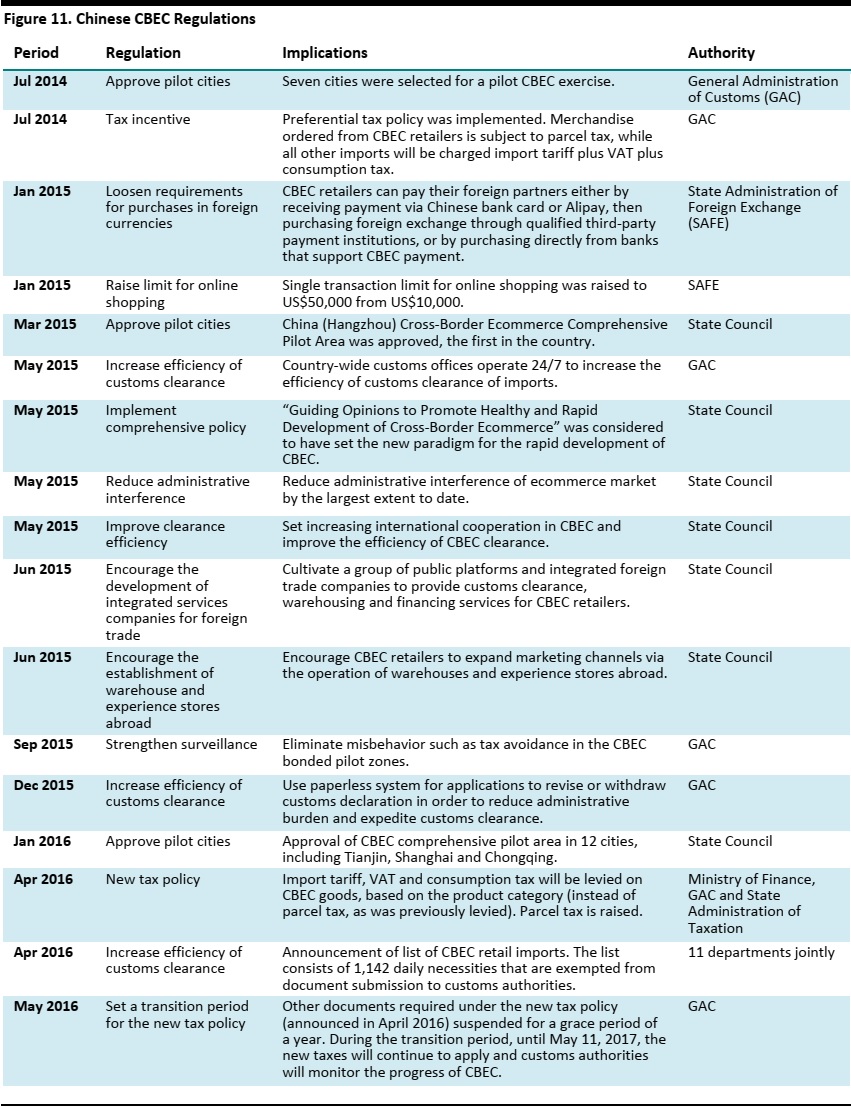

CHINA’S CBEC POLICIES

Chinese authorities have been formalizing regulations for the CBEC industry since the second half of 2014; these rules include tax reforms, the setting up of pilot Free Trade Zones and the expedition of customs clearance, among others. In our view, China’s regulatory reforms are designed to pave the way for systematic development of CBEC.

FAVORABLE POLICY AS A TAILWIND

The new regulations primarily cover these areas:

- Standardize and regulate CBEC practices

- Set up pilot Free Trade Zones

- Increase efficiency of customs clearance

- Support exchange settlement and cross-border payments

- Encourage new CBEC business models

Taken together, these new policies in standardizing CBEC have been effective in establishing regulatory clarity and reducing the risk of import tariff and tax circumvention. However, there are still uncertainties surrounding the uniformity of regulations specific to the Free Trade Zones.

Establishment of CBEC Pilot Zones

The Chinese authorities set up CBEC pilot zones in 10 Mainland cities as a solution for monitoring product quality, protecting consumer interests, and safeguarding the country’s tax and import tariff receipt. The first ecommerce zone was established in Hangzhou, where Alibaba is headquartered.

The Free Trade Zones house bonded warehouses which facilitates cross-border trade. The “Bonded Area Import” model delays the payment of import taxes and duties: imported goods are stored in a bonded warehouse in China until the time of sale. Once sold to the customers, the taxes and tariffs are paid and the goods complete customs clearance.

Striving for Regulatory Clarity

In April 2016, Chinese authorities implemented regulations related to tax and customs clearance certificates for CBEC imports. Under the new regulations, online purchases are subject to imported VAT and consumption taxes instead of parcel tax.

Furthermore, the authorities required that a customs clearance certificate be issued for every imported good that enters the CBEC pilot zones in China. This requirement was subsequently suspended for a transition period of one year due to the uncertainty it engenders. According to Xinhua News, the regulators’ foremost priority is to “facilitate a smooth transition and enhance a healthy development of cross-border ecommerce in China.”

Source: Shutterstock

Source: iResearch/Fung Global Retail & Technology

HOW INTERNATIONAL RETAILERS CAN APPLY CBEC TO THEIR CHINA STRATEGY

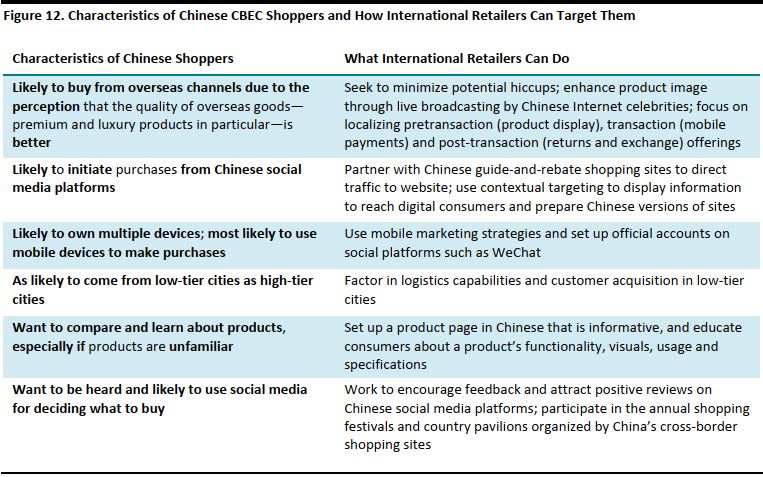

In order to succeed in the Chinese CBEC market, international retailers need to keep pace with changing consumer tastes, product categories and channels. The two primary considerations for merchants that want to create a CBEC strategy for China are the choice of platform and marketing.

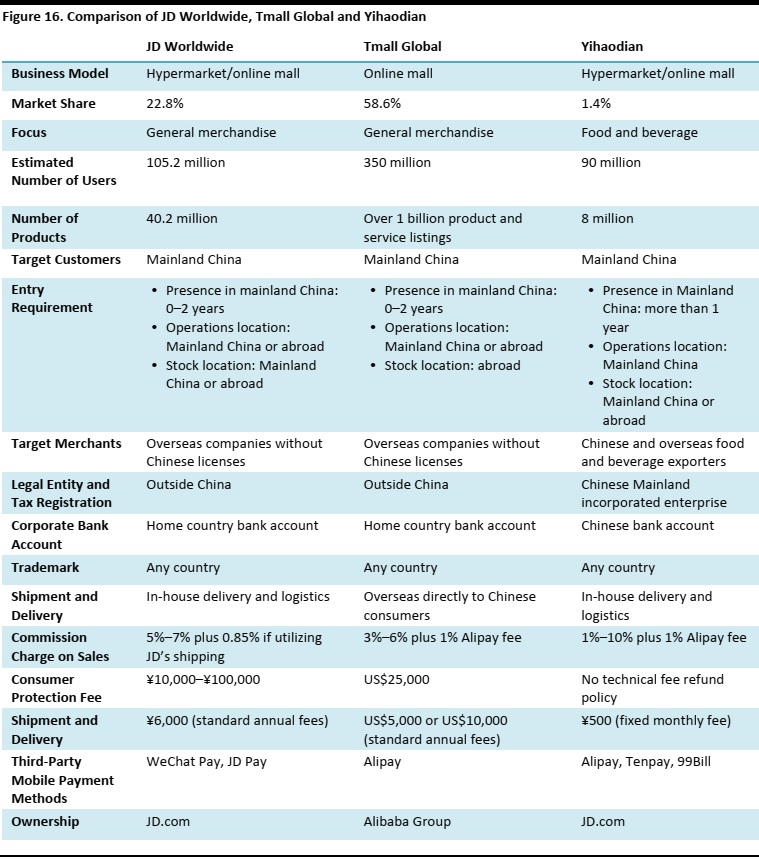

- Platform: One of the primary considerations for international retailers is how they plan to sell their products through cross-border channels. Three relatively popular options, amongst others, include setting up stand-alone websites, working with one of the established CBEC online marketplaces or selling to self-operated platforms which purchase inventory from retailers and distribute themselves. The two largest B2C CBEC online marketplaces are Tmall Global and JD Worldwide.

- Marketing: International retailers need a marketing strategy that ensures their products receive commensurate recognition in China as in their own country. They should be sure they have a Chinese version of their site to help educate Chinese consumers.

MARKETING: KNOW THE CUSTOMER

(PROFILE OF A TYPICAL CHINESE DIGITAL SHOPPER)

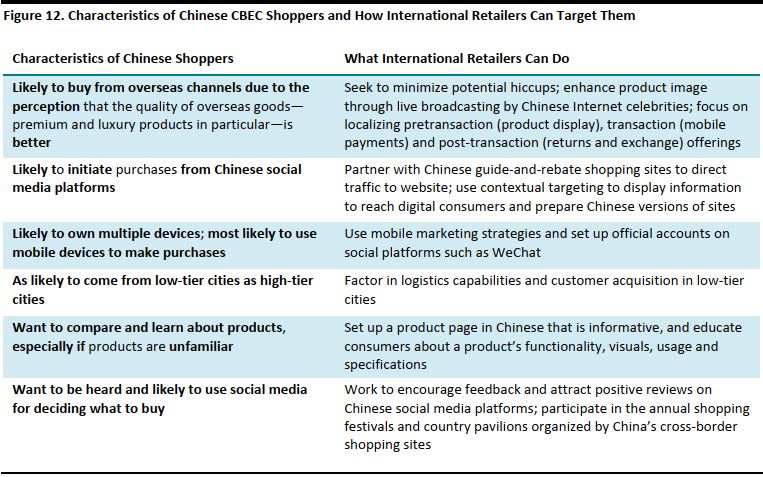

It is critical that international retailers entering the Chinese ecommerce market become knowledgeable about those they are trying to sell to. Below, we summarize the distinct characteristics of China’s typical digital shopper.

Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

INTERNATIONAL RETAILERS’ PROMOTION OF INFANT FORMULA IN CHINA

A number of international infant formula brands have succeeded in getting their products into China via CBEC, and these serve as an illustration of how other international retailers could use CBEC to navigate regulatory changes and changing consumer tastes.

Market Potential of Infant Formula in China

Euromonitor International forecasts that China’s total infant formula market will more than double in the coming years, growing from ¥65.7 billion this year to ¥246.3 billion in 2020. An article in

The Lancet, a leading medical journal, also forecasts that the Chinese infant formula market will more than double, to reach US$70.6 billion.

Source: Shutterstock

Two primary forces have shaped the Chinese infant formula market:

- Concerns about substandard products: The Chinese infant formula market has been defined by a string of scares involving counterfeit and toxic products; these scandals have caused Chinese consumers to turn to international brands.

- Extensive regulatory scrutiny: Chinese authorities have kept a close eye on infant formula, including imports. A recent regulatory change requires that infant formula imported through international websites receive official approval.

The timing could not be better for international retailers selling in China:

- International brands have come to dominate China’s infant formula market due to consumers’ perceptions that they are of superior quality. According to Euromonitor, the market is led by overseas brands such as Nestlé, Mead Johnson and Danone.

- China’s infant formula market is bound to grow due to the official abandonment of the one-child policy in October 2015.

- A string of domestic milk powder scandals has led to a drop in consumer trust of domestic brands, with the Melamine scandal in 2008 as the turning point. In September 2008 in China, ix young children died and 54,000 were hospitalized after dairy firms were found to have added the chemical melamine to watered-down milk to make it look as if their products were high in protein.

Distributing into the Chinese Market

Infant formula is in particular demand in China, and international brands seek to reach Chinese consumers through different distributional channels in order to maximize their profits.

The practice of third parties selling infant formula to Chinese customers has prompted a number of countries, including Australia, Britain, Hong Kong and New Zealand, to limit in-store purchases per transaction. The regulatory limitation functions to reduce parallel trading: private profiteers can resell a 1 kg can of formula in China for as much as three times the Australian price.

Through CBEC channels, international infant formula brands launched a well-timed offensive in the Chinese market which was defined by mistrust for domestic brands.

In response, retailers such as Woolworths have set up online stores to sell their products directly to Chinese customers. The issues that international retailers have to deal with include establishing a presence on a cross-border online platform, marketing and managing logistics.

How Friso Took on Chinese Customers

Royal FrieslandCampina, a Dutch dairy producer, is one of the five largest dairy producers globally. The company plans to increase its Chinese revenues to €2 billion by 2020.

The company has a strategic partnership with Tencent to develop ways of engaging with Chinese consumers for its infant formula brand, Friso. The two companies jointly released “Let Go, Baby,” which is a content-marketing program featuring Chinese stars taking care of children.

The company also sells its Friso formula on its individual store site and on JD.com. Friso’s three products ranked 1, 3 and 4 in the mother/baby category in 2015’s 618 online shopping festival promotion on JD.com.

Source: Friso

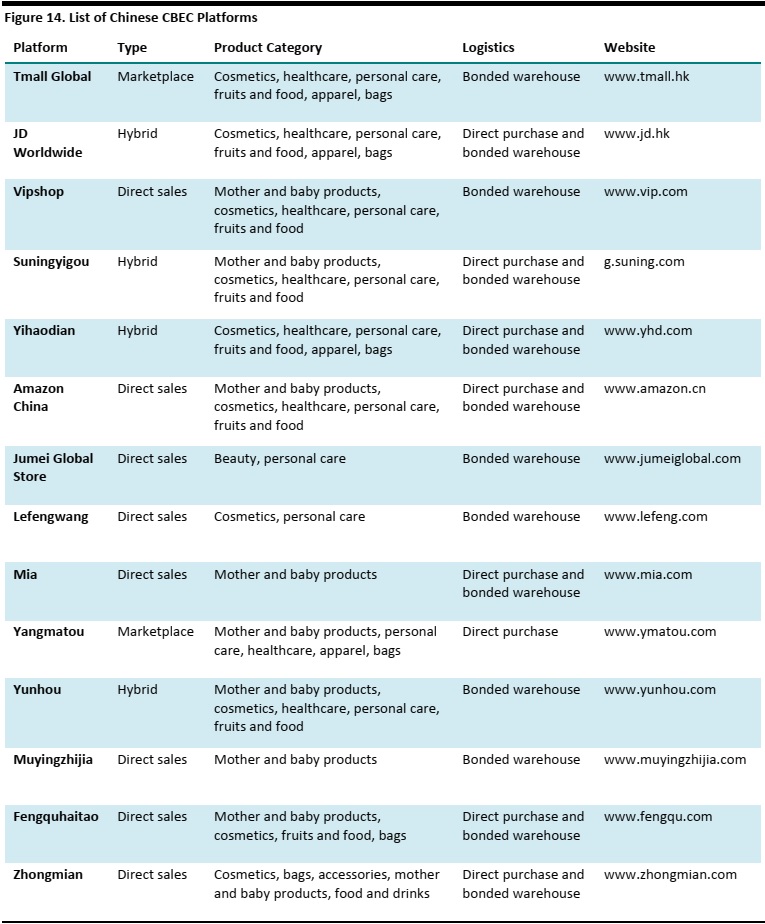

CHOOSING A CBEC PLATFORM

Favorable regulations, consumer trends and technology developments have evolved to enhance CBEC’s appeal as a means for international retailers to distribute in China.

Source: Shutterstock

FACTORS TO CONSIDER

International retailers are advised to have a strategic plan for CBEC which complements their existing China strategy. There is no one-size-fits-all solution and choosing the appropriate CBEC model necessitates understanding the evolving Chinese market and the international retailer’s own business model. Factors to consider include industry and region, scope of services, infrastructure, costs, and presence.

Important questions to consider about a CBEC partner include:

- Who is the platform’s targeted demographic?

- Which product categories does the platform specialize in?

- What is the fee structure?

- Who are the company’s partners?

- What other brands does the company work with?

- What value-added services does the company provide? Marketing? Logistics? Others?

- How does the company deliver?

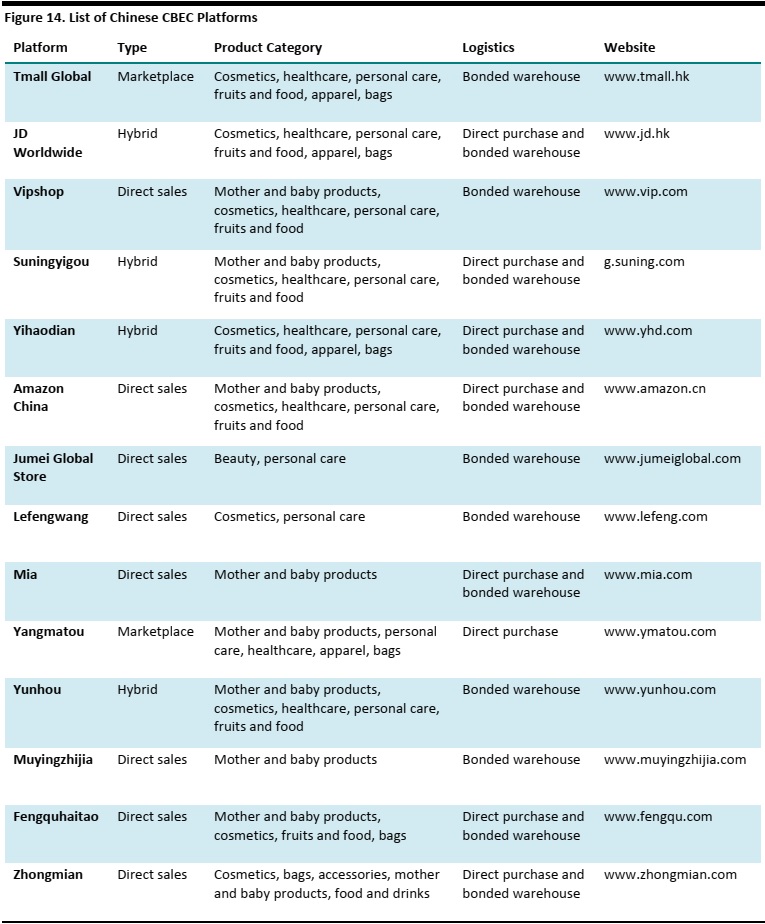

TYPES OF CBEC PLATFORMS

Choosing the right CBEC model for one’s business needs is crucial for growth and success in the Chinese market. Starting a website that focusses on Chinese online shoppers is an obvious approach to international retailers. Further to that, we also introduce other CBEC channels below which we classify according to their operational models:

- Online marketplace (also known as third-party ecommerce platform)

- Online direct sales model (also known as self-operating ecommerce platform)

- Hybrid ecommerce platform

- Others (overseas online shopping and guide-and-rebate shopping model)

Online Marketplace (also known as Third-Party Ecommerce Platforms)

In general, established global brands prefer to set up their own storefronts on online marketplace (also known as third-party ecommerce platforms), as it enables them to interact directly with customers. These platforms, such as Tmall Global, enable retailers to open a storefront on the platform in order to access Chinese online shoppers. An online marketplace can personalize a merchant’s storefront and marketing in exchange for a marketing fee and commissions on transactions. The daily operations of the online store—spanning logistics, customer support, product pricing and marketing—can be handled by the retailer’s own team or outsourced to a third party to manage. These platforms can help international brands penetrate into lower-tier cities in China. However, the costs of these platforms are higher.

Online direct Sales Model (also known as Self-Operated Ecommerce Platforms)

Online direct sales distributors (also known as Self-operated ecommerce platforms) keep their own inventory which they purchase from retailers, and sells directly to customers. Online direct sales distributors require retailers to relinquish some control over their online operations in China. These platforms may be more suitable for smaller brands.

Source: Shutterstock

Online direct sales distributors, such as Amazon.cn and NetEase’s Kaola.com, act as cross-border merchants and operate the distribution, marketing, customer support and sales functions for all imported products. Online direct sales distributors enable international retailers to sell their products in China without registering a company in the country or needing to deal with local regulations and compliance.

The disadvantage for international retailers is that they have little control over their ecommerce sales and strategy in China, because these are controlled by the online direct sales distributor. Online direct sales distributors can promote and offer sales for products at their discretion. Some self-operating platforms are dedicated to specific product categories. For example, Sasa.com is an online direct sales distributor that sells beauty and healthcare products, while Womai.com sells groceries.

Hybrid Ecommerce Platforms

Hybrid ecommerce platforms, such as JD Worldwide and Yihaodian, are combinations of an online marketplace and an online direct sales distribution model. As the name suggests, hybrid platforms not only enable retailers to create their online storefronts, but also buy wholesale from the retailers and sell products themselves.

Other Platforms

Other types of ecommerce platforms include overseas shopping platforms and guide-and-rebate shopping platforms. On

overseas shopping platforms, Chinese customers purchase products from overseas retailers’ websites and have the products delivered via transnational logistics. Examples include g.taobao.com.

A guide-and-rebate shopping platform cooperates with an ecommerce group, with the goal of directing site visitors to complete the purchase through the ecommerce platform. A guide-and-rebate platform earns a commission of approximately 5%–15% from the ecommerce platform. Examples include Etao, Haitaocheng and 123haitao.

Source: Etao

Note: At the time of this report Amazon China’s marketplace hosts only domestic third-party merchants,which is why we are categorizing Amazon China as a direct sales platform when it comes to cross-border ecommerce.

Source: PPjian/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Source: PPjian/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Source: Shutterstock

HOW CBEC IS FULFILLING CHINESE CONSUMERS’ APPETITE FOR JAPANESE PRODUCTS

More Japanese companies are targeting Chinese CBEC shoppers to expand their sales and take advantage of Chinese consumers’ insatiable appetite for Japanese products. The market for Japanese goods bought by Chinese online shoppers will reach JPY¥2.34 trillion by 2019, up from JPY¥0.80 trillion in 2015, according to Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

A Nikkei Group survey of 422 Chinese consumers who shopped online from Japanese sellers in 2015 found that cosmetics were the most popular category, accounting for 53.6% of sales, followed by audiovisual and information technology equipment at 29.6% and food at 28%.

Wandou: When a Mobile App Intersects with CBEC

Wandou (which roughly translates as “the princess and the pea”) is a Chinese mobile shopping app that uses professional shoppers in Japan to procure merchandise for consumers in China. For Chinese shoppers, the app is a reliable way of buying Japanese merchandise, ranging from toilet-seat covers to toothpaste, that is perceived as safe and of high quality. The app offers free shipping for orders over CNY¥300 (US$45).

Rakuten: Cooperates with China’s CBEC Platforms and Payment Solutions Providers

Rakuten, Japan’s largest online marketplace, is also reaching out to the Chinese market as it faces mature growth at home. There have been a number of recent announcements regarding Rakuten and its Chinese counterparts:

- In June 2016, Rakuten opened an online flagship store on Kaola.com and it markets its brands via the media assets of NetEase, which owns Kaola.com.

- In December 2015, Rakuten set up an online store on JD Worldwide.

- In April 2014, Rakuten Global Market added Alipay as one of the payment methods it accepts in order to make it convenient for Chinese consumers to complete purchases.

Alibaba Japanese Merchandising Center: A Bridge Between Japanese Companies and China’s CBEC Market

Alibaba hosted representatives from over 200 Japanese brands at the opening of its Tokyo center in May 2016 to facilitate Japanese companies’ access to CBEC in China and to complement its globalization strategy. Alibaba provides participating Japanese companies with assistance in areas such as sales channel setup, marketing support and product selection in order to help them better cater to Chinese customers.

OVERVIEW OF LEADING CBEC PLATFORMS IN CHINA

Chinese shoppers’ appetite for and trust in international goods has caused ecommerce platforms such as Alibaba and JD.com to launch global shopping channels. Below, we provide an overview of some leading CBEC platforms where international retailers can sell to Chinese shoppers.

Tmall Global

Tmall Global, launched in 2014, is Alibaba’s cross-border platform and China’s largest online marketplace for international branded merchandise. It enables international brands, with or without a physical presence in China, to set up exclusive storefronts and to sell directly to Chinese customers.

Tmall Global has core competencies in traffic acquisition, merchant adoption, marketing and global logistics. Its suite of offerings is made available through Alibaba’s ecosystem: payment is facilitated through Alipay, Alibaba’s online payment service, while advertising and marketing are supported by tools such as Zhitongche (a paid search ranking system) and Zuanzhan (display banners). Logistics is supported by the Cainiao network.

Tmall Global works directly with international distributors such as Costco, Macy’s, Metro, Shiseido and Uniqlo. A flash-sales channel for luxury items was launched on Tmall’s app, partnering with Mei.com, which also features a cross-channel component.

TMALL GLOBAL’S 8.8 SALES BROUGHT THE WORLD TO CHINA

Source: Shutterstock

The Tmall event is distinguished by its focus on consumer education; Alibaba’s 11.11 Shopping Festival focuses on sales.

JD Worldwide

JD Worldwide, the cross-border service of JD.com, uses both the online marketplace and direct sales models. The online marketplace model allows brands to open individual storefronts to sell directly to Chinese consumers. Brands can utilize JD’s in-house logistics service, a feature that distinguishes JD Worldwide from Tmall.

JD Worldwide also operates direct sales on its platform, buying inventory from overseas distributors and selling it directly to Chinese customers. The company manages all logistics and marketing under this model.

JD Worldwide is strengthening its position as distributor for brands and has forged partnerships with international ecommerce players such as eBay, Unilever, Rakuten and Lotte.

Specialized Models

International brands that cater to a certain niche can benefit by selling on more specialized CBEC platforms, such as:

- Jumei Global: the cross-border platform of Jumei.com, a Chinese online cosmetics retailer.

- Yihaodian (YHD): one of China’s largest online retailers of food and beverages. It is owned by JD.com (previously owned by Walmart).

- Vipshop International: launched in 2014, this is the cross-border platform of Vipshop and focuses on selling international fashion to Chinese consumers. The company is upgrading its international sector by adding more high-end overseas products to its portfolio and expanding its customer base.

Source: JumeiGlobal

Source: China Briefing/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Source: Bain & Company

CONCLUSION

We expect CBEC will drive the next leg of ecommerce growth as Chinese ecommerce companies and international retailers launch globalized versions of their portals. By selling through CBEC, international retailers can reach Chinese shoppers regardless of whether the retailers have a physical presence in China.

International retailers are advised to have a strategic plan of entry, whether they choose to enter the Chinese CBEC market on their own, selling wholesale to an ecommerce direct sales distributor or to set up sites on online marketplace, most of which are affiliated with leading Chinese ecommerce players. When creating a CBEC strategy, companies need to consider factors such as clientele, region, scope of services and costs, and they should ensure they have a solid understanding of evolving Chinese consumer preferences and regulations.