Web Developers

Executive Summary

In this report, we examine Western grocery retailers’ and wholesalers’ push into the India and look at the features of the Indian grocery market. We also share observations and images from our on-the-ground research in India, where we visited the stores of several local and international retailers and wholesalers. Finally, we discuss the barriers to entry and the opportunities that are present in the Indian grocery sector. The latest data from the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) show that Indian consumer spending on food, beverages and tobacco jumped by 17.6% year over year to $336 billion in the fiscal year ended March 2014. We estimate that spending on these categories rose to over $400 billion in the year ended March 2017. (These data are at constant 2016 exchange rates to remove the effects of currency fluctuations.) According to MOSPI, Indians allotted fully33% of their total consumer expenditure to food, beverages and tobacco in fiscal year 2014. Several factors have historically limited the entry of international grocery retailers and wholesalers into India. The government allowed FDI in the wholesale trade from 1997 onward, which paved the way for Metro Group and Walmart to open cash-and-carry businesses in India. FDI was permitted in the multibrand retail sector beginning in 2012, which allowed international retailers to invest in direct operations in India, albeit only up to 51%. So far, only Tesco has used this route to enter India, which it has done through a 50/50 joint venture with Trent Hypermarkets. Dutch retailer Spar has a presence in India through a franchise model with Max Hypermarkets. In 2017, the Indian government began allowing FDI in food-only retail at 100%, but the cap for nonfood grocery is still 51%. In order to increase India’s attractiveness as an investment destination, we think the government needs to further liberalize foreign investment policy. In our view, it also needs to work on improving infrastructure considerably, including by subsidizing both high-quality storage facilities closer to farms—which would help farmers store their produce safely and reduce wastage—and retail spaces that would encourage retailers to set up operations in the country.

Spar Hypermarket at Mantri Mall, Bangalore. Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Introduction: India’s Grocery Retail Landscape

Grocery shopping in tropical, agrarian India is very different from grocery shopping in the West. Rural and urban communities are dotted with vegetable and fruit vendors peddling fresh produce on pushcarts and tiny stores, informal markets and stalls that sell the provisions an average household needs. These vendors are usually found alongside modern grocery retailers’ outlets that sell local produce, imported food and other products. In this report, we examine the push of Western grocery retailers and wholesalers into India’s grocery landscape, look at the features of the Indian grocery market, share observations and images from our on-the-ground research on local and international retailers and wholesalers in the country, and analyze the barriers to entry and opportunities in the sector. Our companion report on international apparel retailers in India can be found at FungGlobalRetailTech.com.Sizing the Indian Grocery Market

We begin by examining some key details of the Indian retail sector, food and beverages’ share of that sector, and some of the characteristics that are unique to the Indian grocery market. The scale of the consumer market and the growth momentum in India make it an attractive destination for investment. The country has the second-largest population in the world, with 1.3 billion people, and is the world’s fourth-fastest-growing economy. According to the latest estimates from the International Monetary Fund, India’s economy will increase by 7.2% in 2017.Indian Grocery: A $400+ Billion Market

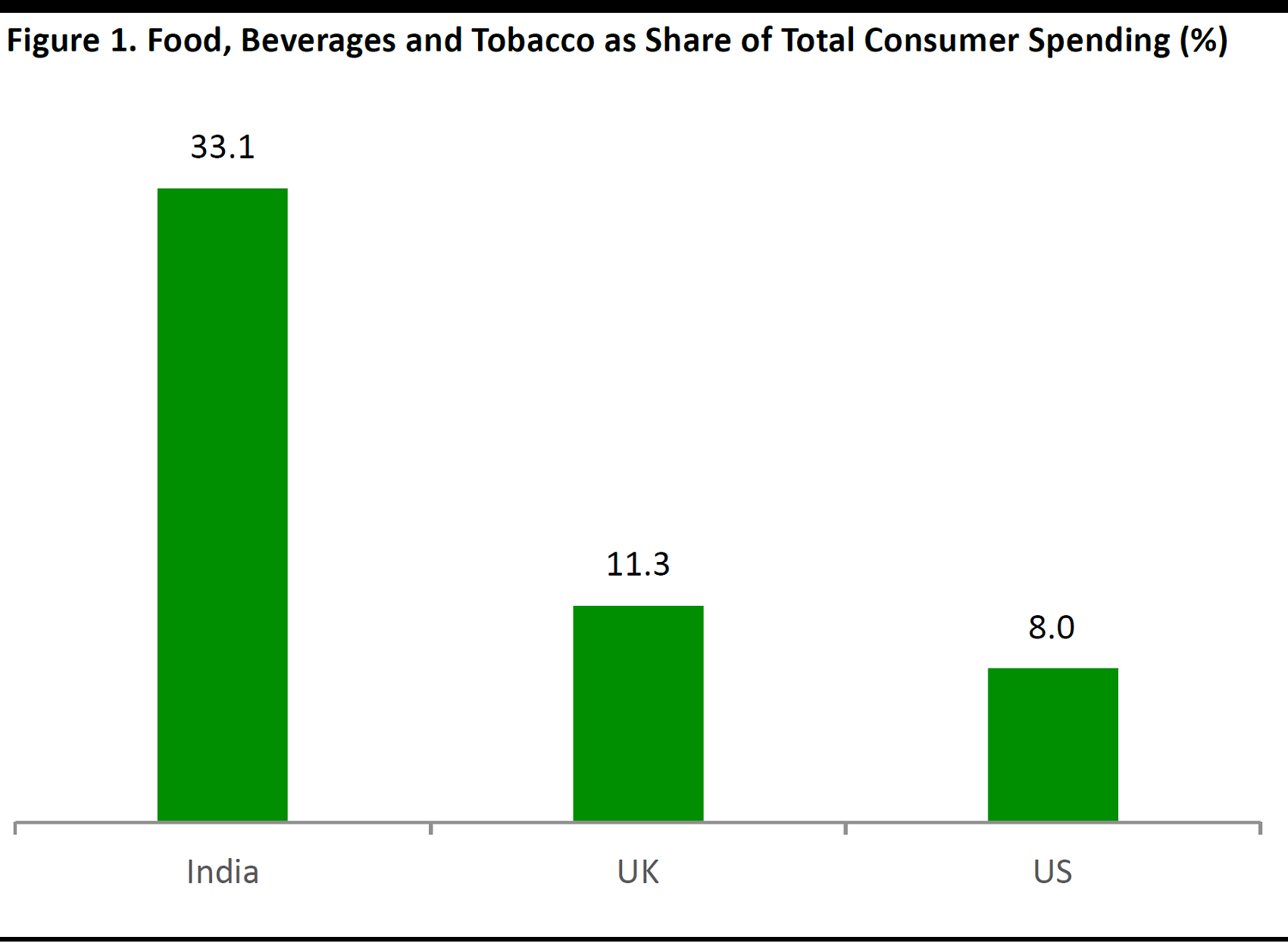

In 2016, Indian consumers spent approximately $645 billion at retail, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF). That organization expects the retail sector to grow at a CAGR of about 12% through 2020, when it will reach almost $1 trillion. The average Indian consumer spends substantially more on food than on discretionary items such as clothing and entertainment, which is typical for a developing economy. The latest MOSPI data show that Indian consumer spending on food, beverages and tobacco jumped by 17.6% year over year to $336 billion in the fiscal year ended March 2014. We estimate that Indian consumers spent over $400 billion on food, beverages, and tobacco in the fiscal year ended March 2017. These figures are at constant 2016 exchange rates to remove the effects of currency fluctuations. Food is a staple expenditure, and as a general rule, consumers in less economically developed countries direct a greater share of their spending to basic retail categories than do consumers in more economically developed countries. As we show in the table below, food, beverages and tobacco account for a much higher proportion of total spending in India than in Western markets such as the UK and the US.

India data are FY14; US and UK data are calendar 2016 Source: MOSPI/UK Office for National Statistics/US Bureau of Economic Analysis/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Main Characteristics of Indian Grocery Consumers and Grocers

There are many characteristics unique to diverse and populous India that define its grocery landscape, including:1. Low modern retail penetration: Many Indians still transact through traditional retail channels rather than through modern retail channels. As we discussed in our previous reports in the India Rising series, various estimates suggest that modern retail penetration is only about 6%–8% in India. It is even lower in food retail, at about 2%–3%, according to consultancy Wazir Advisors.

2. Highly fragmented market: Grocery vendors in India range from a few large, modern hypermarkets and supermarkets to many smaller convenience stores to numerous farmer’s markets, roadside sellers and vendors that sell produce on pushcarts near people’s homes.

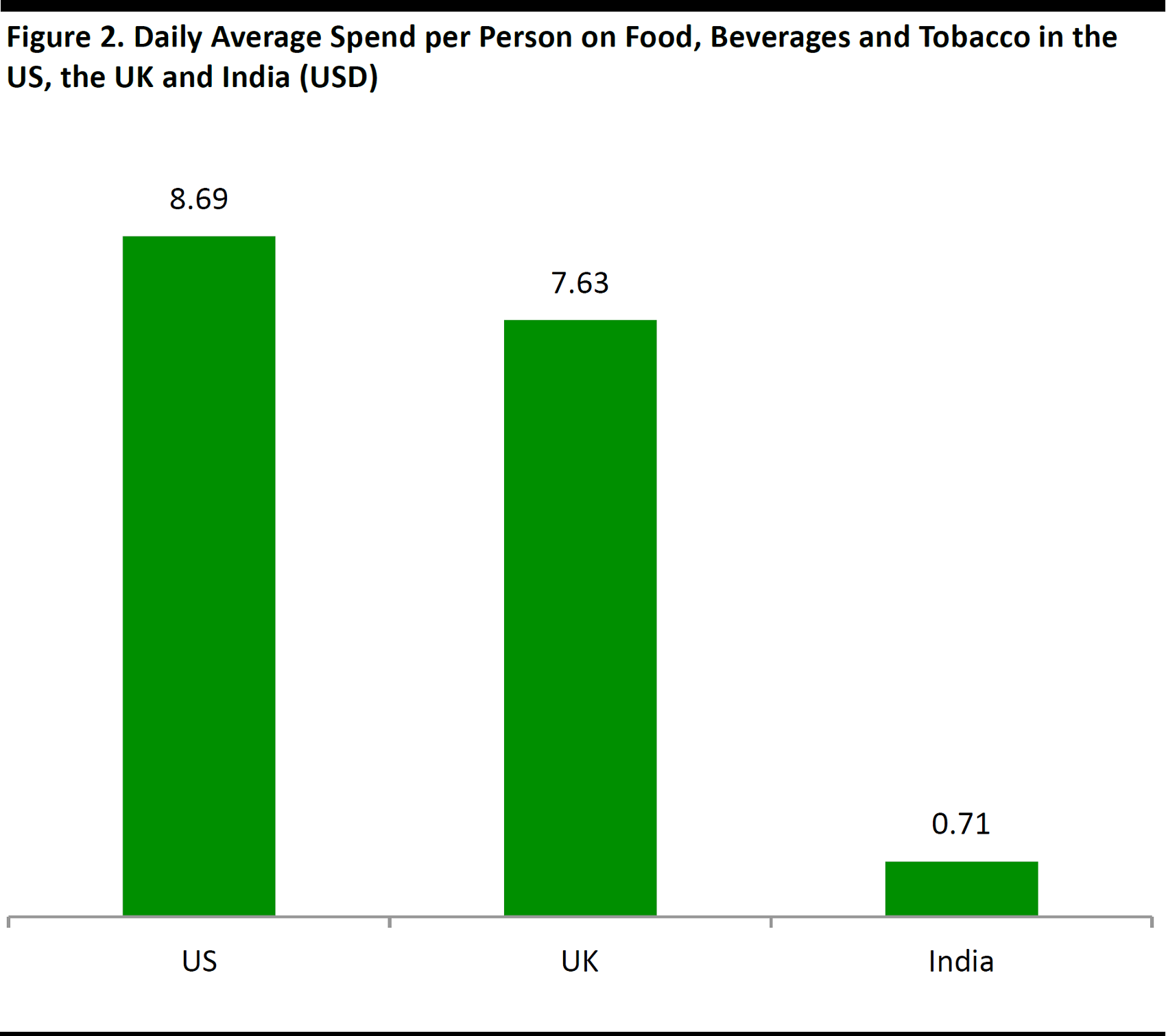

3. Small basket sizes: Despite India’s high growth trajectory and size, its consumers are less affluent than their peers in many other large economies and in the other BRIC nations. The average Indian grocery basket size is less than INR 1,000 ($16), according to the Business Standard, an Indian newspaper. Our analysis based on data from national statistics bodies indicates that the Indian daily average spend per person on food, beverages and tobacco was a fraction of that seen in the US or the UK.

In USD at 2016 exchange rates. India data are FY14; US and UK data are calendar 2016. Data are for at-home food and beverages, excluding foodservice. Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics/US Census Bureau/UK Office for National Statistics/Eurostat/MOSPI/Fung Global Retail & Technology

4. Regional culture and weather define food habits: India’s culture and weather vary greatly across regions, and heavily influence the food and diet of its people in different areas. For example, rice is a staple grain in the South of India, while wheat is predominant in other parts of the country.

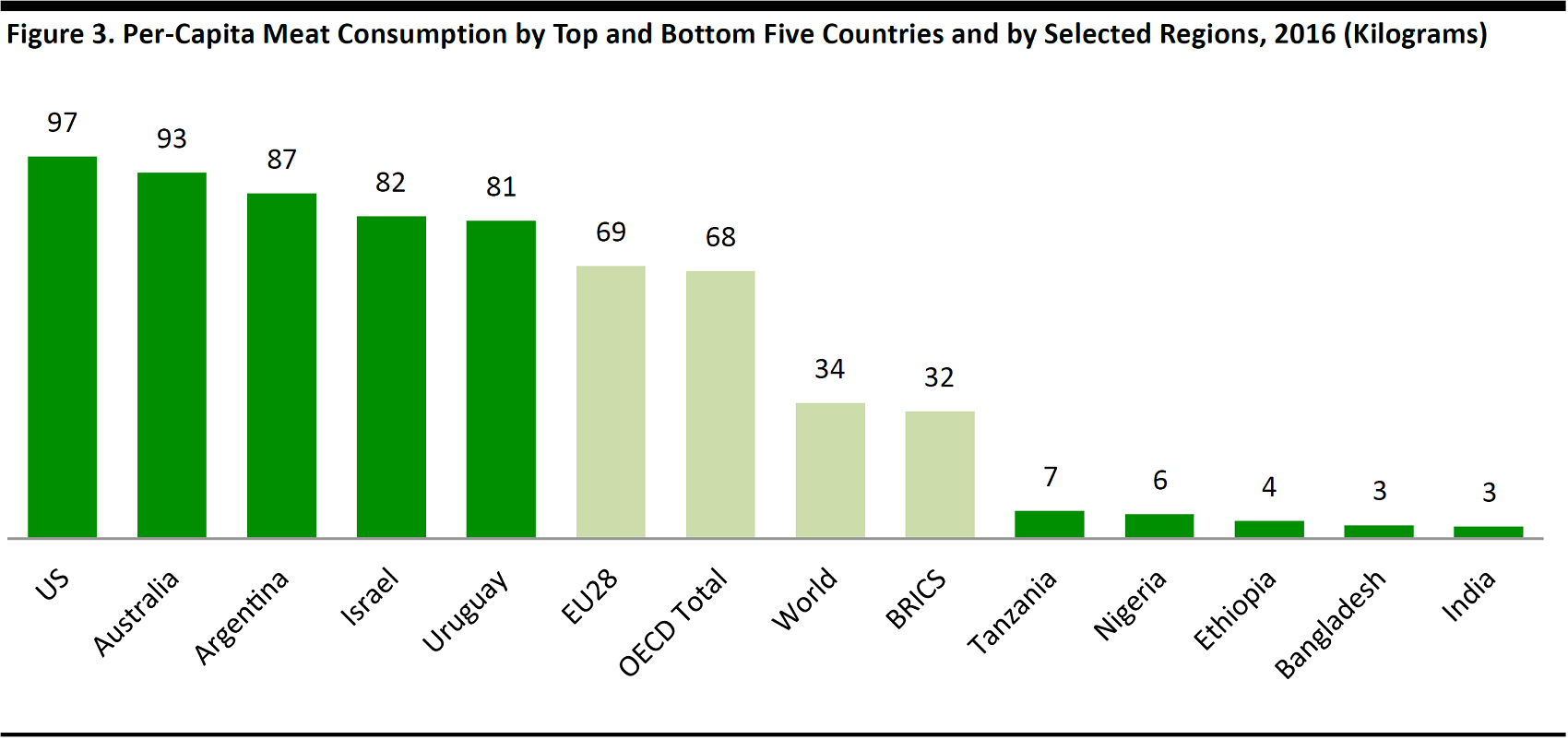

5. India is heavily vegetarian: According to the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, some 30% of Indians are vegetarians. In comparison, some 10%–12% of UK and US consumers are vegetarians, according to a 2013 Harris Poll. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD) indicate that, in 2016, India had one of the lowest meat consumption rates in the world, at three kilograms per capita. While religious observance is a primary reason for this, low meat consumption also tends to be associated with lower disposable incomes.

Source: OECD.org

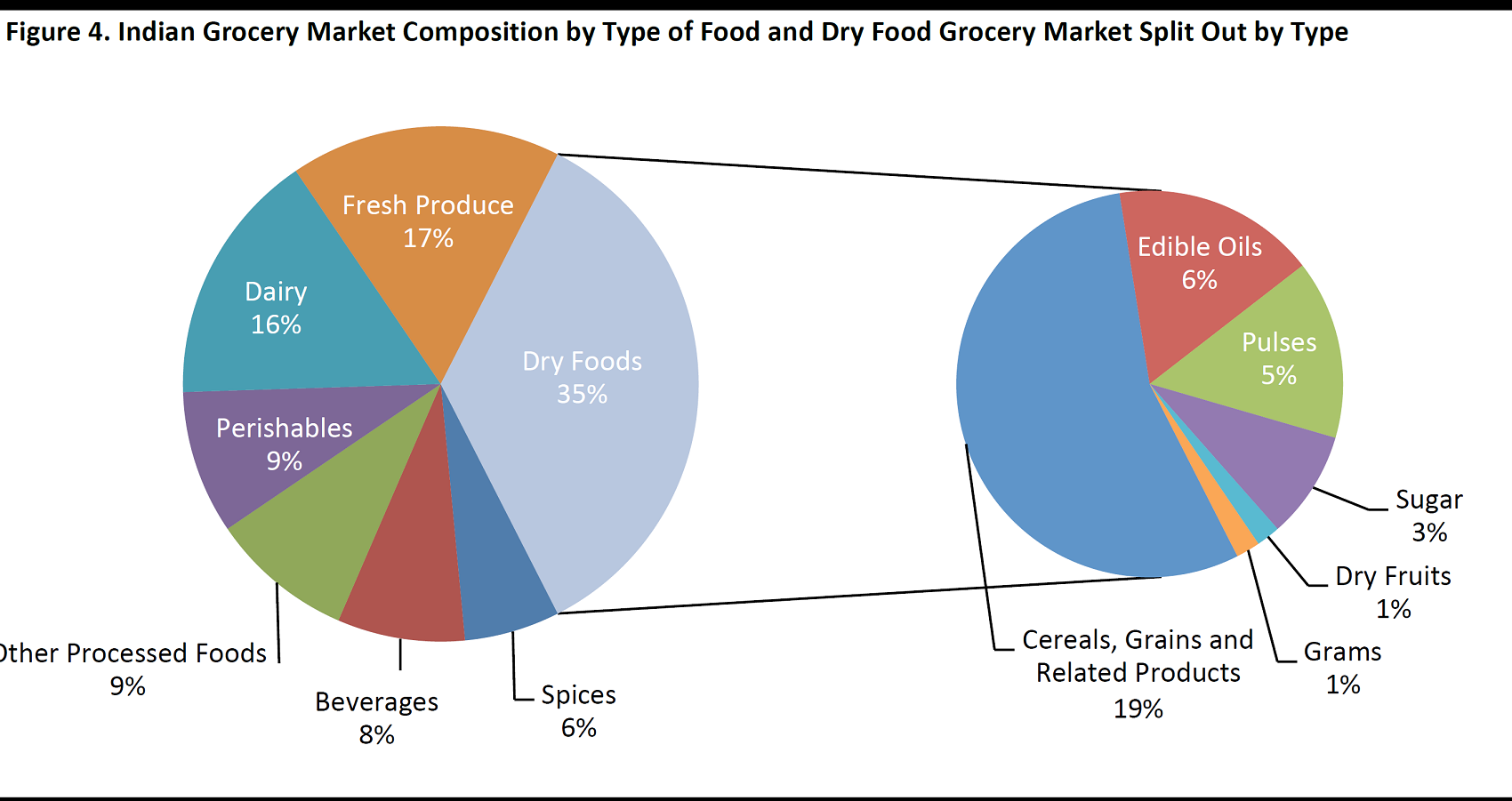

6. Dry food constitutes the largest part of the grocery market: Dry food comprises 35% of the grocery market in India, where consumers rely heavily on cereals, grains and grams (dried legumes) to form their staple diet. Fresh produce and dairy are also key constituents, accounting for 33% of the Indian diet.

Our on-the-ground research in India suggests that most consumers who shop through modern retail stores tend to buy the majority of their dry food and nonfresh produce at larger shops and supermarkets, while they tend to buy their fresh produce at neighborhood convenience stores and vegetable cart vendors.

Source: MOSPI/India Food Forum

7. The concept of maximum retail price (MRP): In India, federal laws stipulate that consumer product manufacturers determine the maximum price at which their products are sold, and that they print that price on the product packaging. The government instituted this regulation to protect consumers and restrict retailers from selling goods at artificially inflated or deflated prices.

The atmosphere at Indian grocery retail and wholesale stores is typically highly promotional, so a fixed ceiling price protects consumers from being overcharged, while a floor price protects smaller retailers from the larger retailers that charge less in order to attract customers.

In our report Deep Dive: International Apparel Retailers in India—Jumping the Hurdles in Pursuit of Growth, we discussed how the Indian government’s efforts to open up the economy helped ease international retailers’ entry into the country. We briefly recap this liberalization below and highlight foreign investment regulations regarding food retail in India.Economic Reforms in Grocery Wholesale and Retail

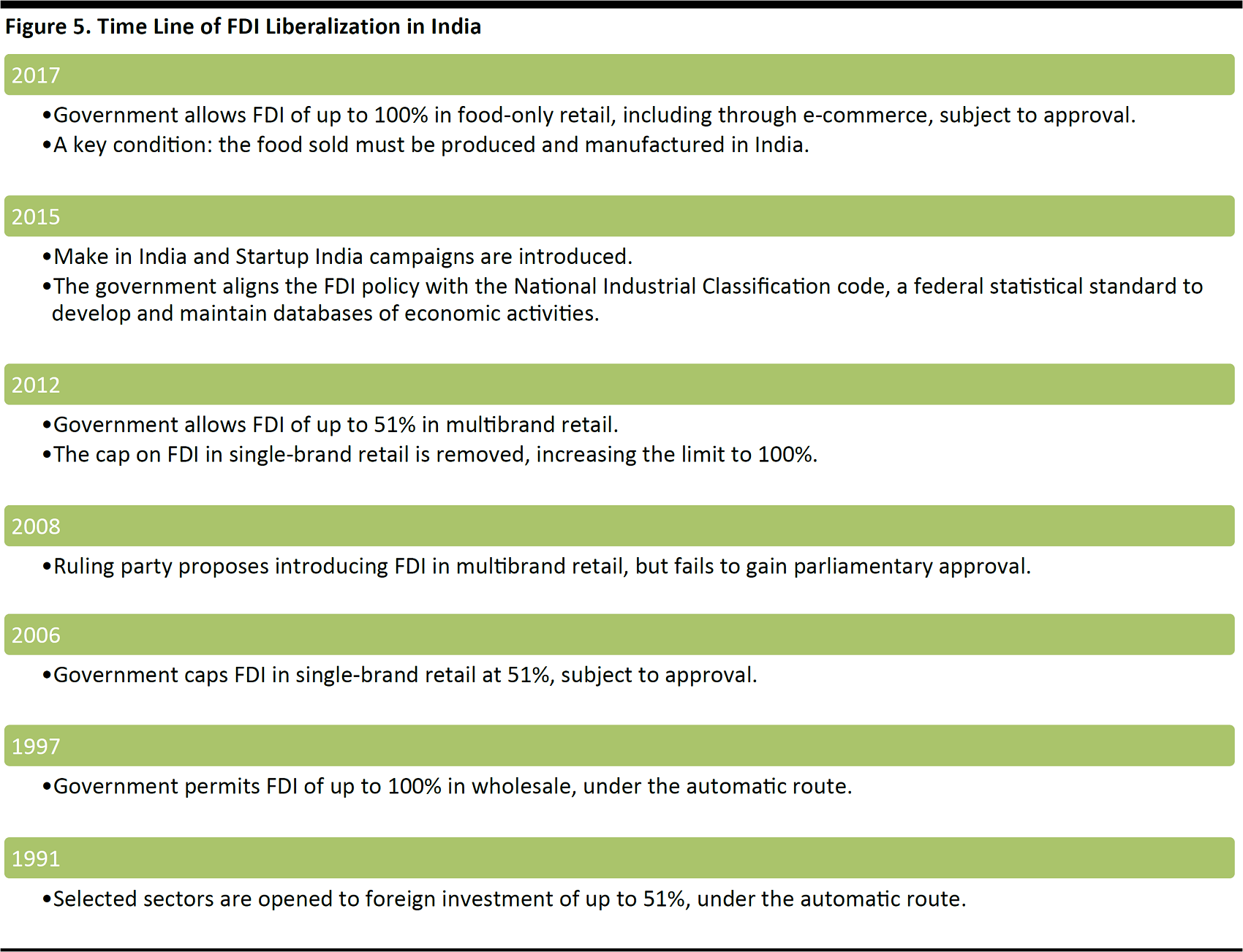

The figure below illustrates some of the major milestones in the liberalization of India’s economy, which we then discuss in more detail.

Source: TechSci Research/IBEF/Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India/Fung Global Retail & Technology

Foreign investors were allowed to invest in and operate direct wholesale stores in India beginning in 1997. This paved the way for cash-and-carry businesses, such as Metro Cash & Carry, to open stores in India much earlier than international retailers. In order to take advantage of this opportunity, Walmart and Carrefour set up cash-and-carry formats to cater to wholesale consumers, as the retail sector—in which they typically operate in their home and global markets—was not yet open to foreign investment. The Indian government enforced its highly protectionist regulation of the retail sector until about 2006, when it first allowed FDI of up to 51% in single-brand retail, subject to approval. So, retailers such as Gap and Zara, which sold only their own-brand products, were allowed to open stores in India in partnership with a local company, with a maximum ownership stake of 51%. The move applied to other categories of retail, too, but in grocery, it is impractical for most retailers to sell only own-brand products. In 2012, the government removed the cap on single-brand retail investment and also allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail (which includes department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands), subject to government approval. Beginning in February 2017, the government allowed 100% FDI in the sale (including through e-commerce) of food products that are manufactured or produced in India. The government stipulates that retailers clearly separate their food-only business from their nonfood business for regulatory purposes. Due to these measures, various international retailers have employed different routes to doing business in India.Entry Routes for Foreign Brands and Retailers in India

The government has established several routes through which international firms can trade in India. Under the non-FDI route, there are two methods: licensing and franchising. Licensing: Under this method, the owner of the brand (the licensor) leases the rights to use the brand name to the retailer (the licensee), allowing the retailer to stock and sell the branded merchandise. Franchising: Similar to licensing, franchising allows a retailer (the franchisee) to use a brand’s (franchisor’s) intellectual property, as well as its business model, marketing strategy and distribution model, in order to sell the brand’s goods. In India, Max Hypermarkets owns the rights to operate stores under the Spar brand name. Under the FDI route, there four methods through which international retailers can sell goods in India: joint venture (JV), wholly owned subsidiary, limited liability partnership, and extension of the foreign entity via a liaison office, branch office or project office. JV: A JV is an enterprise in which two or more firms have pooled their capital and other resources. The 50/50 JV between British grocer Tesco and Trent Hypermarket is the most famous example of this method being employed in grocery retail in India. Through the JV, the companies operate stores under the Star Bazaar and Star Daily banners. Wholly owned subsidiary: With this method, an organization (the parent or holding company) sets up a new company that is incorporated as a domestic business in India. The entire equity stake of the subsidiary is owned by the parent company. Metro Cash & Carry and Walmart’s Best Price stores operate as wholly owned subsidiaries. Carrefour also operated under this method in the years it did business in India. Limited liability partnership: With this model, the partners in a firm have limited liabilities, i.e., one partner cannot be held responsible for another partner’s mismanagement of the company. Extension of the foreign entity via a liaison office, branch office or project office: International companies can also set up an office in India that represents their interests under one of the above structures. The establishment of a liaison office, branch office or project office is subject to further rules laid out by the Indian government and central bank.Key International Players in Indian Grocery Retail

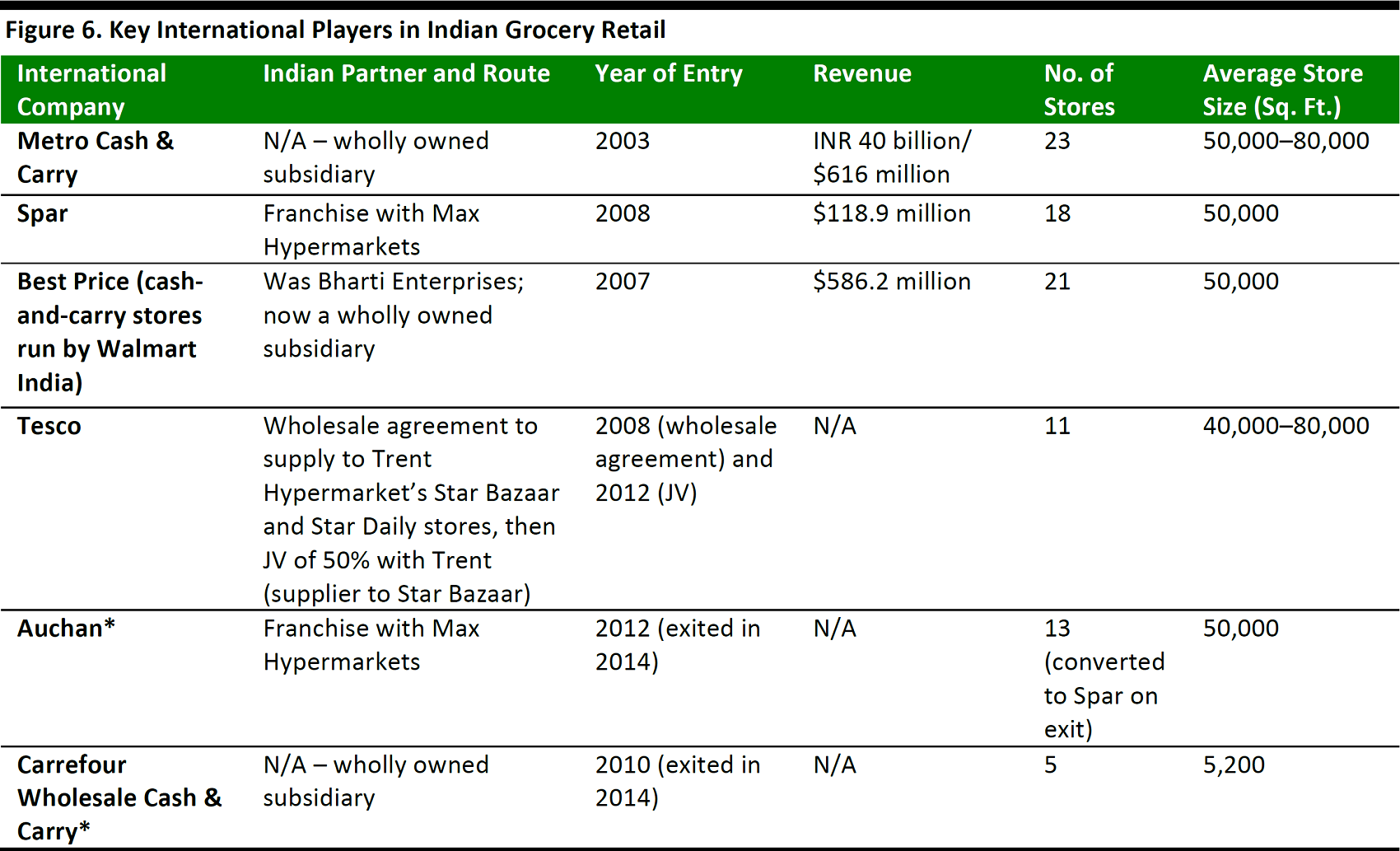

In this section, we discuss some of the major international names operating grocery retail and wholesale stores in India and those that they have partnered with, and share photos and observations from our store checks in various locations in Bangalore. Currently, there are four key international players in Indian grocery retail and wholesale: Spar, Metro Cash & Carry, Walmart (through its Best Price stores) and Tesco. French retailers Carrefour and Auchan each operated in the country for a few years, but exited due to a lack of clarity about foreign investment in food retail.

*No longer operating in India Source: Company reports/S&P Capital IQ

Members of the Fung Global Retail & Technology team visited some of the stores of the above retailers as well as some of their domestic competitors’ locations. We discuss our key observations below, and readers can find more images in our Facebook gallery.Store Tours: International Wholesalers/Retailers

Metro Cash & Carry

Metro Cash & Carry in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Store traffic: We visited the store at around 4p.m. and foot traffic was heavy (despite the quiet appearance in some of our photographs), which is not unusual. The store has wide aisles, but it was challenging at times to push a cart around due to the high number of shoppers in the store, and nearly all registers were busy, with long lines of customers waiting to checkout.

Metro Cash & Carry in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Assortment: The store had a good mix of conventional foods and a small selection of organic foods. We noticed a strong presence of Metro’s own brand, Aro, across the dry and packaged-grocery and household care categories. Indian brands dominated other packaged-food categories, while there was a more pronounced presence of international brands, such as Dove, Nivea and L’Oréal, in the beauty and personal care aisles. In clothing and footwear, we noticed a few private labels and several brands from well-known clothing companies in India. In the electricals section, we saw many popular global brands such as Samsung and LG. Price: Metro’s own brand was, of course, priced lower than organic and premium brands, but higher than low-end brands. We compared the prices of Bengal gram flour—a staple ingredient in Indian cuisine—from Metro’s own brand, Aro, and the 24 Mantra Organic and Sri Bhagyalakshmi brands, and found that the Aro flour was priced between the other two brands. Shelf labels indicated the MRP of the product displayed, the price at which Metro was selling the product and the savings for the customer. Other facilities: The store had an on-site café, customer restrooms, a customer service counter for stamping the warranty cards of purchased products, and a board where customers could write their suggestions or list products they could not find at the store. Metro also offers delivery of products bought at the store.

Delivery signage atMetro Cash & Carry in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Spar

Spar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Store traffic: When we visited around 11:30a.m., traffic was thin at the store. Assortment: We noticed the presence of Spar’s own brand across the food and household maintenance categories, but it was not dominant over the other labels. Among the personal care categories, we noticed a strong presence of international brands, such as Nivea, Neutrogena, Olay and Garnier. There was a wide selection of clothing from Spar’s partner, Max Hypermarkets, for sale at the store.

Spar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Price: Spar prides itself on operating under the concept of “Everything Below MRP,” and this was evident at the store we visited. Most products were priced below the MRP, even if only slightly, and those that were heavily discounted had a label that said “Promotion” highlighted in red or one that said “Best Deal.”

Spar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Other facilities: The store had an on-site concession for refreshments, but it was minimally stocked. We did not see any restrooms, but did notice a customer service counter and a loyalty club counter. We also noticed a sign inside the store indicating that customers could shop online at SparIndia.com.

E-commerce site signage at Spar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Store Tours: Domestic Retailers

Big Bazaar

Big Bazaar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Store traffic: We visited a little after 5p.m. Store traffic was high and the fresh produce areas were the busiest. Assortment: Big Bazaar sells conventional food and selected organics. We noticed a reasonable assortment of Big Bazaar’s private label, Tasty Treat, alongside other brands. Personal care products were mainly from the large, international brands.

Big Bazaar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Price: Most products from third-party brands at Big Bazaar were offered at a discount to the MRP, but we did not notice many multibuy offers, such as three-for-two or buy one, get one free. Other facilities: There were checkout registers on nearly every floor in the store. There was signage indicating product categories and facilities, but some signs were partially hidden by products that were stacked up in front of them. Restrooms and seating were available for customers. We also noticed that the store had a Bangalore One Centre—which is an office set up by the local government where people can pay utility bills, renew public transportation passes and make other payments to civic bodies.

A Bangalore One Centre office in Big Bazaar in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

HyperCity

HyperCity in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Store traffic: There were few people at the store when we visited, probably because it was early in the afternoon and many people were at work. Assortment: HyperCity’s own brands, such as Fresh Basket, had a clear presence on the shelves, but not more so than other brands. Though HyperCity has an exclusive supply agreement with Waitrose, we found few products from the British brand at the store, perhaps because it was a small-format one. Members of our team had previously observed a whole aisle of Waitrose products in a different, large-format, HyperCity store. We did see several other international brands, such as Jamie Oliver, Hellman’s and American Garden, at the store we visited.

HyperCity in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Price: The atmosphere in the store was highly promotional. We noticed special discounts labeled “Hyper Savers” and buy-one,get-one-free offers.

HyperCity in Bangalore Source: Fung Global Retail & Technology

Other facilities: There was a customer service desk, but we did not observe any other special facilities in the store. Overall, we found the international grocery stores were more spacious, and had clearer signage and wider aisles than the domestic grocery stores. The international retailers also appeared to have fewer shopfloor staff.Opportunities in Indian Grocery Retail and Barriers to Entry

In India’s organized grocery retail market, there are numerous homegrown modern retailers, but only a handful of international retailers. Given the country’s diversity and complexity, there appear to be more social, commercial and political barriers to entry into the grocery market than there are in other retail segments—but there are many opportunities for growth in Indian grocery, too. We spoke with Surya Shastry, Managing Director of Phalada Agro Research Foundations, to understand more about the underlying opportunities and hurdles in Indian grocery retail. Phalada is an exporter of private-label organic spices and packaged food to US retailers and is also the third-largest organic food brand in India. We combined Shastry’s observations with our own analysis to create the following list of opportunities in the Indian grocery market:1.Growing organic grocery segment and preference for healthier food: Shastry told us that sales in the organic grocery segment in India have been growing at around 30% annually over the last three to four years, and that the government has implemented policies to increase the farmland devoted to organic agriculture. Organic food currently constitutes a small but rapidly growing category across most modern grocery retailers in India, which cater largely to young, urban families.

2. A substantial portion of the population is employed in farming and agriculture: The agricultural sector employs the greatest proportion of people in India. Fully 51% of total employment in India in 2010 was in agriculture, according to the latest available figures from the World Bank. We estimate that the proportion was about 48% in 2015. Farmers have strong unions in India and are provided many subsidies by the government. Hence, they have strong bargaining power. The entry of large international players will allow for direct negotiations with the farmers and cut out intermediaries, which will result in a win-win situation for both parties, as well as more transparency in the supply chain.

3. Proximity to source and India’s landscape for cultivation: FDI norms stipulate that a major portion of merchandise sold is sourced from India, as large parts of the country are agricultural areas and a majority of the working population is employed in agriculture. Locating sourcing factories and offices close to these agricultural areas will enable retailers to transport food from farm to market efficiently.

4. Youthful, modern working population: India has one of the youngest populations in the world. Some 66% of the country’s 1.3 billion people are between the ages of 15 and 64. Many members of the urban working class increasingly prefer to shop at organized food retail shops due to the variety available at those stores.

5. Government’s plans and initiatives to boost foreign investment: The Indian government’s move to lift the cap on foreign investment in food retail indicates that it is open to growing the sector. Though the government has indicated that it does not intend to lift the restriction on the retailing of nonfood items in the same stores in which food is sold, many international retailers hope that it will open up the sector further in the near future.

6. Widening palates and preferences for international cuisines: As more Indians travel around the world, their desire to try out international cuisines at home is also growing. Many of the ingredients and much of the equipment required to prepare international dishes are available only at modern retailers’ stores, making them preferred shopping destinations for those interested in international cuisines.

However, before international retailers are able to take advantage of all of these opportunities in India, the following barriers and threats need to be addressed:1. Lengthy bureaucratic procedures and loose food safety regulations: Setting up any sort of establishment in India involves going through incredibly lengthy bureaucratic procedures, which need to be streamlined. Also, food safety regulations in India are not as stringent as in the West. Shastry told us that farmers do follow strict international regulations in organic food cultivation and labeling for products that are exported, but that they do not follow them as carefully for products sold to the domestic market. As the image and reputation of retailers and brands depend on the quality of the products sold, strict regulation is a burning issue that the government needs to address in order to attract more international retailers.

2. Inadequately developed infrastructure: Because the majority of food retail in India is unorganized, there has been little reason and opportunity to develop infrastructure related to food retail. Warehouses, cold-storage facilities and other necessary links in the supply chain are inadequate. In fact, a government survey in 2016 found that India wastes approximately 67 million tonnes of food each year, worth about INR 920 billion ($14 billion), due to storage facilities that inadequately address pests, weather conditions and gluts in supply.

3. Rise of e-grocers: We looked at the rise of homegrown disruptor Bigbasket in detail in our second report in the India Rising Bigbasket and another domestic player, Grofers, have been slowly gaining market share in dry food retail, as has international giant Amazon.

Shastry mentioned several advantages that packaged-food suppliers have in working directly with e-grocery players. He said that online marketplaces allow retailers to display a wider assortment and range than could be stocked at a physical store, and that the big e-grocers also have logistics and other operational functions in place that ease the delivery of products from producer to consumer. Any new entrants to the Indian grocery market will certainly need to assess the threat from the rapidly growing e-grocery retail sector, Shastry said.

4. Numerous intermediaries in the supply chain: Food producers tend to work directly with retailers in urban areas, but they need to engage distributors or super-stockists to supply retailers in smaller cities and less-connected neighborhoods, which could reduce the producers’ margins.

5. Unplanned urbanization: Urban areas have been growing rapidly in India, but infrastructure has not evolved at the same pace. In some areas, roads are narrow and poorly maintained, making them unsuitable for large vehicles that carry products to market. Furthermore, alack of mobile connectivity in remote areas makes it hard for companies to communicate effectively.