Web Developers

Executive Summary

This is the third report in our India Rising series focusing on the startup ecosystem in India. Here, we examine various e-commerce enablers—firms that provide support functions in the online retail process, such as logistics providers and software providers. We analyze how these ancillary businesses have taken shape as a result of online retailing’s growth in India. We identify three key types of enablers: logistics firms; technology, or IT infrastructure, firms; and fintech, or financial technology/payment gateway firms. India’s e-commerce sector is big, and it is growing quickly. Online sales in the country totaled some $30 billion in 2015, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), and they are expected to touch $120 billion by 2020.

Source: Shutterstock

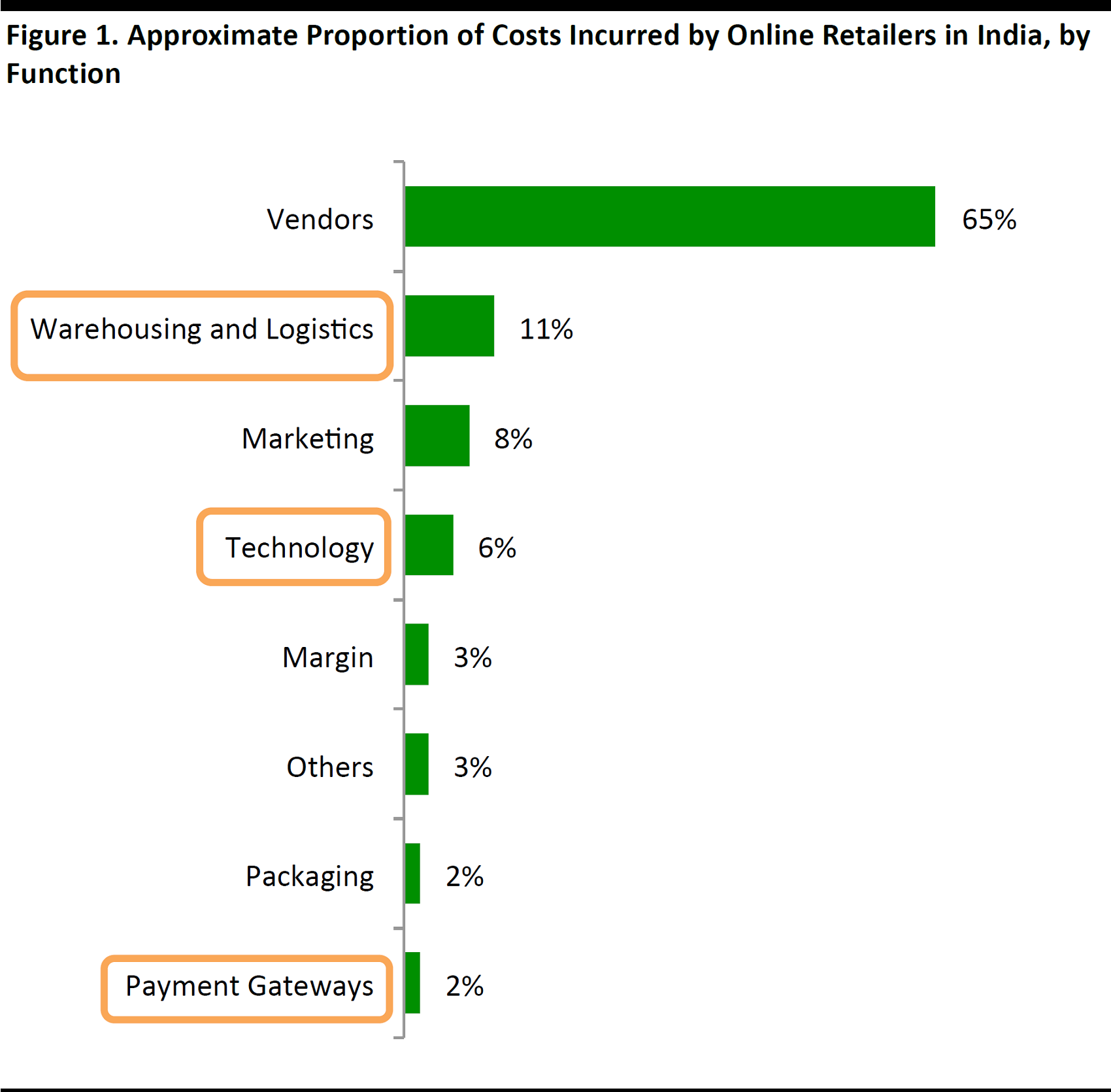

Enabling firms take slices of this market. According to analysis from management consultancy Technopak Advisors, the bulk of revenue at a typical stable-growth e-commerce firm is allocated to the vendor (i.e., the seller of the product) or to the product cost itself. Some 11% is accounted for by the warehousing and logistics functions. Technology, which encompasses the infrastructure and staff needed to maintain and run e-commerce websites and apps, utilizes 6% of revenue, and payment gateways account for 2%. Together, these three enabling functions take up 19% of total revenue at a typical e-commerce firm. In 2015, India spent about $302 billion, or 14.4% of its GDP, on logistics and transportation, according to The Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry of India(ASSOCHAM). The average cost of logistics as a percentage of GDP for developed countries is about 8%. Euromonitor International estimates that logistics alone accounted for a substantial 16% of total retail costs in India in 2015. Based on data from Technopak Advisors and IBEF regarding the approximate portion of total revenues that Indian e-commerce firms allocated to technology in 2015, we estimate that these retailers spent some $1.8 billion on technology for running their websites and apps that year. According to a report by Google and the Boston Consulting Group, the Indian digital payments market was worth some $50 billion in 2016 and is expected to grow tenfold, to $500 billion, in 2020. Some retailers may feel that they can exercise greater control over their operations and costs if they use in-house resources rather than third-party providers. However, e-commerce is still in a nascent stage in India compared with global markets, and until domestic players grow large enough to justify bringing logistics, technology and digital payment operations completely in-house, e-commerce enablers have enormous potential to capitalize on the still-young online retail sector in India. Currently, even the largest domestic online retailers do not possess the same scale as international giants Amazon and Alibaba.An Introduction to E-Commerce and its Supporting Businesses in India

In India, the retail and e-commerce sectors may not be as mature as they are in Western countries, but several tech-driven disruptors are making strides to provide better choice, lower prices and greater convenience to Indian online shoppers. In our first report in the India Rising series, we looked at the factors that make India a booming startup destination and at the major players in the country’s startup ecosystem. In our second report in the series, we examined four major e-commerce disruptors: Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr, and BigBasket. We looked at five factors that have shaped online retail in India, the reasons for the disruptors’ success and the imminent threat that domestic e-commerce operators face from international e-commerce giants Amazon and Alibaba. We summarize those five factors in the first section of this report. In this, our third report in the series, we examine various e-commerce enablers, and identify three key types of businesses that support the online retail process: logistics firms; technology, or IT infrastructure, firms; and fintech, or financial technology/payment gateway firms.

Source: Shutterstock

Through the specialist services they offer, businesses in these categories enable the e-commerce process from the point that customers begin the online shopping journey to the point that they receive the products they have ordered. Outsourcing certain functions to other firms help e-commerce retailers focus their capital expenditure on core activities until they build scale and can bring these functions completely in-house.E-Commerce in India and the Ancillary Businesses that Support it

India’s e-commerce sector is big, and it is growing quickly: online sales totaled some $30 billion in 2015, according to the IBEF, and are expected to touch $120 billion by 2020. We begin with a recap of some of our headline findings on e-commerce from our second report in this series:1. There is a lack of modern infrastructure: India’s retail industry is overwhelmingly unorganized (i.e., traditional) and highly fragmented. Various estimates suggest that organized retail (i.e., modern trade) constitutes only 6%–8% of total retail in India. This means that a very large portion of the country’s retail sector remains to be captured by modern retailers.

2. Less affluent consumers look for low prices: Even with the economy growing, many Indian consumers still have limited incomes, which spurs demand for low-price marketplaces. The average Indian has little to spend on discretionary items each year, as evidenced by spending on leisure goods and services, which capture barely 1% of Indians’ total annual consumer spending.

3. Consumers like to pay cash on delivery (COD): India is a cash-centric economy where some 68% of transactions are made with cash, according to brokerage firm CLSA. World Bank data indicate that bank account penetration in India was only 53% in 2014. COD payment allows more shoppers to buy online and is a fundamental feature of e-commerce retail in India. Fully 57% of online shoppers in India cited COD as their preferred payment option, according to a 2015 survey by A.T. Kearney, Google and GfK.

4. The scale and youth of the Internet user base boosts e-commerce: The sheer size and youthful nature of the Indian Internet user and shopper base have powered growth at e-commerce startups. According to brand agency We Are Social, some 462.1 million Indians accessed the Internet in January 2017. However, that figure constitutes only about 25% of India’s 2016 population.

ASSOCHAM reports that India had one of the youngest Internet user bases among the BRIC nations in 2015: about 52% of Indians who were online that year were between the ages of 26 and 35.5. Foreign direct investment (FDI) restrictions and the relatively late entry of Amazon in India have benefited domestic players: Domestic companies have benefited from government policies that restricted FDI in Indian retail. Between 2006 and 2012, the government implemented several policies that allowed foreign retailers to operate in India through physical stores, but restricted them from selling online. Marketplace sites were effectively exempted because FDI was permitted in business-to-business e-commerce—and marketplaces are technically technology platforms that facilitate trade between buyers and sellers. This helped existing Indian e-commerce marketplaces raise larger amounts of foreign funding, while also paving the way for Amazon to operate a marketplace using domestic sellers in India beginning in 2013.

These factors have indirectly supported the growth of auxiliary businesses that enable online retail in India.How E-Commerce Costs are Split

Below, we chart the approximate division of costs for Indian e-commerce retailers that are seeing stable growth, according to analysis by Technopak Advisors. Together, enabling functions account for 19% of the total input costs of stable-growth e-commerce retailers in the country. While the bulk of revenue is allocated to vendors or product costs, some 11% is taken up by warehousing and logistics functions. Technology, a function that involves infrastructure and the staff needed to maintain and run e-commerce websites and apps securely and effectively, utilizes 6% of revenue. Payment gateways account for 2% of e-commerce revenue.

Source: Technopak Advisors

Enablers by Sector: Logistics, Technology, Fintech

In the following sections, we analyze our three focus areas: logistics, technology and fintech.1. Logistics

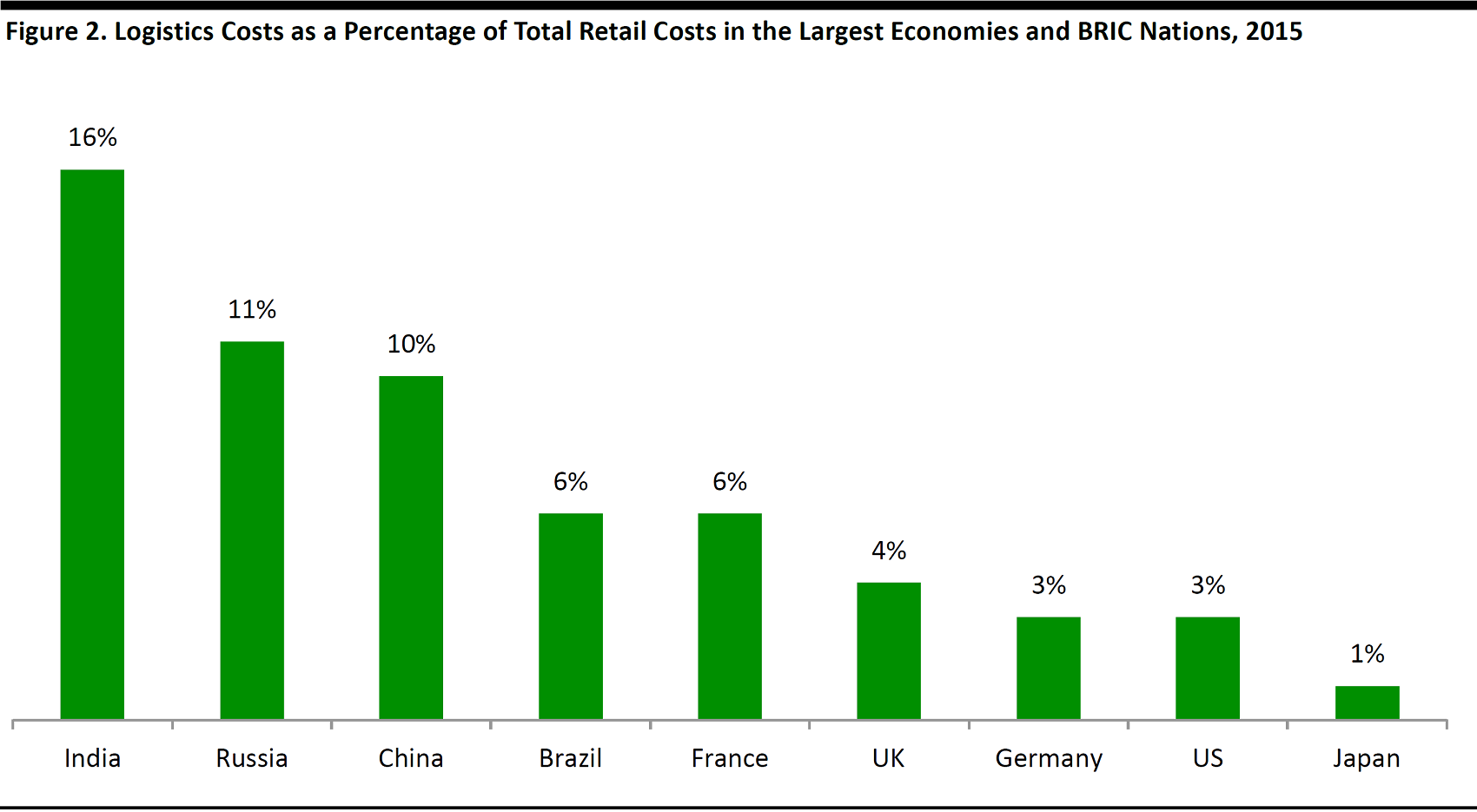

Logistics is a critical function for e-commerce marketplaces and retailers, as it involves the safe and prompt movement of goods from the vendor or warehouse to the customer. In India, only a few major international logistics firms—such as Blue Dart (a subsidiary of DHL), TNT and FedEx—serve the market, which is dominated by a large number of smaller intermediaries and third-party logistics players that work with shippers to manage clients’ logistics operations. Urban planning of cities and towns is also less organized in India than it is in the developed markets. There are more than 20,000 postal codes in the country, but only about 10,000 are serviced by existing logistics providers. Inadequate infrastructure and the lack of organized urbanization pose an enormous challenge to logistics and transport businesses operating in the country. In 2015, India spent about $302 billion, or 14.4% of its GDP, on logistics and transportation, according to ASSOCHAM. By comparison, the average cost of logistics as a percentage of GDP in developed countries is about 8%. ASSOCHAM expects India’s spending on logistics to increase to $307 billion by 2020. Euromonitor International estimates that logistics alone accounted for a substantial 16% of total retail costs in India in 2015. In China, logistics accounted for 10% of total retail costs that year, and in Western markets, the proportion was much lower.

Source: Euromonitor International

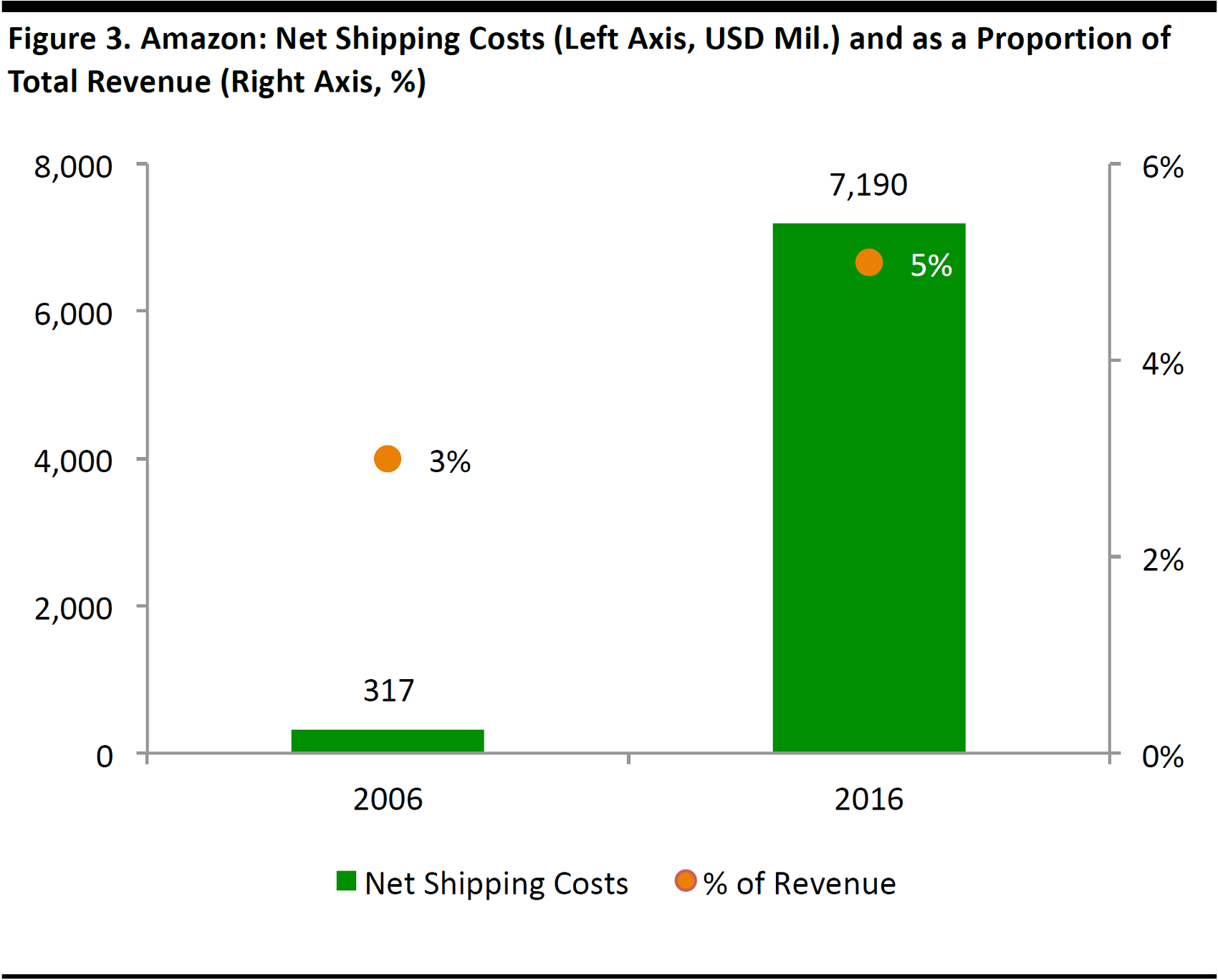

For further context, we looked at Amazon’s spending on logistics. We do not have similar numbers for privately held Indian e-commerce firms. In 2006, Amazon’s net spending on shipping and logistics was $317 million, which equaled about 3% of its revenue that year. Net spending on logistics includes the company’s spending on shipping and logistics minus shipping charges and Prime membership fees paid by customers. In 2016, Amazon’s net shipping costs were about $7.19 billion, which was 5% of its revenue that year. As spending on logistics rose significantly over the decade, Amazon invested a great deal in fulfillment centers and warehouses to bring a large portion of its post-order operations in-house, thus allowing it greater visibility into and control over the process and costs. Growing its in-house logistics operations to support the rise in sales also helped Amazon achieve economies of scale and reduce its per-unit costs to ship; third-party logistics firms may provide fewer concessions based on scale, thus making their services more expensive. Source: Statista/Amazon

Source: Statista/Amazon

Flipkart, India’s largest e-commerce marketplace, told news reporters in 2015 that the company would spend more than $500 million over the next five years to expand its network of warehouses and fulfillment centers in India. Around the same time, Snapdeal indicated that it would spend about $200 million during that fiscal year to expand its delivery operations.

Over 2016, these e-commerce players incurred enormous losses that led to them implementing many cost-cutting measures, including downsizing some of their delivery operations. With logistics costs taking up a substantial portion of revenues, many e-commerce players, including Flipkart, Snapdeal, Amazon and BigBasket, already use outside specialists to fulfill a significant part of their logistics operations, while the rest is fulfilled by their in-house teams.

Below, we profile selected Indian logistics enablers.

Delivery Service: Delhivery

Delhivery is India’s first logistics firm to concentrate entirely on e-commerce deliveries. Unlike other courier delivery firms that cater to businesses across various sectors, Delhivery’s focus has allowed it to create solutions specifically tailored to the needs of the e-commerce sector, such as IT and back-office infrastructure for web shops.

Source: Delhivery.com

Its client roster spans about 950 e-commerce companies, including marketplaces such as Flipkart, and the company has received some $127 million in funding as of early 2017, with a large portion of it coming from hedge fund manager Tiger Global Management. Delhivery expects to achieve about $120 million in revenues for the year ending March 31, 2017, CEO Sahil Barua told Indian financial newspaper The Economic Times in October 2016. The newspaper claims that 65% of the Indian online marketplace delivery segment is controlled by Amazon Transportation Services and Flipkart’s logistics arm, Ekart. When Barua spoke with the newspaper in 2016, he hinted at the possibility of Delhivery launching an IPO soon, but more recent reports suggest that the company is looking first to raise about $100 million in funds, led by private equity firm The Carlyle Group and Chinese conglomerate Fosun.Logistics Solution Platform: Locus.sh

Locus develops algorithms to enable efficient delivery of e-commerce orders. We met with CEO and Founder Nishith Rastogi to learn more about Locus and how it is helping some of the largest online retailers in India move their goods from warehouse to customer. The firm was established in 2015, after Rastogi’s location-based women’s safety app, RideSafe, became an instant success in India,and he identified an opportunity to adapt it for e-commerce deliveries. Rastogi eventually found a way to expand the app into a comprehensive suite of logistics solutions that work as an add-on to delivery fleet management software, such as the kind created by Delhivery and others.

Source: Locus.sh

Locus has received $3 million in funding so far and is backed by GrowX Ventures, Beenext, Blume Ventures and Exfinity Venture Partners. Locus’s core application helps delivery service providers identify the best routes based on order deliveries for the day, taking into account traffic, terrain, neighborhood and other factors. A second solution it recently introduced is a 3D packing engine that visualizes and suggests the most efficient way to pack and place merchandise in a delivery vehicle based on the nature and dimensions of the products and the time and venue of delivery. Rastogi noted that developing algorithms for efficient delivery in India, where road terrain and mapping are complex and unsophisticated due to a lack of infrastructure, is not the biggest challenge. He said that a bigger difficulty is that the attitude toward delivering on time is generally casual in the country, and that changing human behavior to ensure more timely delivery will be challenging. Locus has been inspired by both the work culture at Amazon and its intense focus on using metrics to make data-backed business decisions, a focus that many Indian startups lack. Rastogi said that this is one of the factors holding back progress among Indian e-commerce players.Collection Service: Smartbox

Smartbox is India’s first firm to create automated lockers from which shoppers can collect their orders after keying in a code. These operate in a similar way to Amazon Lockers, which have been installed at many locations in the US and Europe. Smartbox ran a pilot trial with 70 terminals in Delhi in 2015, and the lockers proved popular among shoppers. The company now has plans to install about 1,000 terminals across some of India’s largest cities, including Bangalore, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad and Pune, by March 2018. The terminals also allow shoppers to pay for their orders when they collect them, instead of requiring them to pay online in advance.

Source: Smartbox.in

2. Technology

The technology function broadly refers to the infrastructure and staff needed to maintain and run e-commerce websites and apps securely and effectively. As all functions in a business tend to use technology in some form or other, the references to technology in this section specifically regard the infrastructure and applications that affect the running of websites and apps; we are not referring to technology used for other business functions such as human resource management or financial management. Based on the approximate portion of total costs allocated to technology as outlined by Technopak Advisors and IBEF’s data for average e-commerce revenues in India in 2015, we estimate that online retailers spent some $1.8 billion on technology for running their websites and apps in 2015. Below, we profile some of the many firms in India that are leveraging traditional and emerging technology to create software applications that enable or promote online sales.

Visual Search, Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR): Preksh Innovations

Preksh Innovations creates AR and VR software solutions for retailers’ websites, Facebook pages and mobile apps. The software helps shoppers browse a physical retail store online and look at products. It is developed on top of Google Maps’ Street View function. We met with one of the founders of Preksh, M.A. Kodandarama, to understand how Indian e-commerce retailers are using emerging technology to enable sales. The company began as a partner for Google Street View, and management realized that the same technology could be applied in a retail context.

Source: Preksh.com

Preksh wanted to bring a live, store-like interaction to online consumers and so created a solution that helps shoppers navigate through a physical store, online. It allows users to view products that they are interested in and buy them with the click of a button. The company was established in 2015 and was part of the Target Accelerator Program in Bangalore. Its total seed funding is over $250,000, obtained from founders, angel investors and competition prize money from the Amrita TBI Pitchfest in India and K-Startup Grand Challenge in South Korea. Preksh’s unique selling proposition is that its solution easily integrates with the client’s e-commerce or inventory management system for a seamless omnichannel customer experience. The “Store View” function helps keep customers engaged by allowing them to buy a product through a pop-up window on the same page, instead of requiring them to navigate to a different page. Competitors’ solutions that provide a similar function tend to lead customers to a different web page and fail to provide real-time prices, offers and availability, Kodandarama said. This makes the page “unfriendly” and can result in the customer abandoning the shopping journey. What Kodandarama described is generally referred to as “friction” in the shopping journey. Internet speeds in India are still slow compared with the global average, and retaining the customer’s attention is challenging when a web page loads slowly. Preksh’s solution keeps the customer focused on the same page, negating the problem. Another challenge in India, Kodandarama said, is that retailers in the country prefer to use solutions that have been tested and proven successful, rather than exploring something new and original. He indicated that this mindset has inhibited the growth of many software product-based startups and that firms need to take calculated risks and encourage innovation, like the Target Accelerator did with Preksh. Doing so will help retailers understand the implications of using new technology better and, thus, they will be able to provide domain-specific expertise and feedback that will help startups such as Preksh improve and tailor services to retailers’ needs.

E-Commerce Management: Unicommerce

Unicommerce is a software application that helps sellers manage their inventory across multiple marketplaces. The Indian e-commerce sector is dominated by marketplaces, which means these kinds of services have a large potential market.

Source: Unicommerce.com

Unicommerce’s software helps companies connect their warehouse functions with their online stores and facilitates effective order fulfillment. As of 2014, the company had received about $10 million in funding from Tiger Global Management. In 2015, the firm was bought by Jasper Infotech, the parent company of marketplace Snapdeal. Unicommerce works with Snapdeal and many other big names in Indian e-commerce, including Myntra, Jabong and Urban Ladder.

Chat-Based Artificial Intelligence (AI) Assistant: Niki.ai

Niki.ai is a chat-based assistant, or chatbot, that helps shoppers purchase products, book cabs, order food and take care of banking needs. Niki was established in 2015 and is funded by renowned industrialist Ratan Tata and entrepreneur Ronnie Screwvala.

Source: Niki.ai

The firm’s current focus is to develop the assistant purely for conversational commerce and not include productivity functions, such as the ability to schedule appointments or type messages, that the AI assistants from Google and Apple offer. Startup data and analysis firm Crunchbase indicates that the firm had raised $440,000 in disclosed funding as of December 2016.3. Fintech

Fintech in India has received much attention from global players in the last several years. Indian technology news website Inc42 reports that some $1.77 billion was poured into the Indian fintech sector through 158 deals between 2014 and 2016. It also estimates that the funding received in 2015 alone by India’s largest fintech player, Paytm, accounted for fully 38.5% of the total funding received in the sector between 2014 and 2016. E-commerce marketplaces Flipkart, Snapdeal and Amazon have also made forays into the digital payments space in India. Flipkart has its own wallet, Flipkart Money, and Snapdeal bought mobile payment app FreeCharge. Amazon runs a service called Pay with Amazon. However, none of these match Paytm’s position in India.Digital Payments: Paytm

Digital wallet provider Paytm is the biggest disruptor so far in the Indian payment tech market, which was worth some $50 billion in 2016. The burgeoning market is expected to grow tenfold, to $500 billion, in 2020, according to a report by Google and the Boston Consulting Group.

Source: Paytm.com

Paytm’s wallet service enables consumers to pay for mobile phone allowances, travel tickets, utility bills and goods they buy online. At the India Digital Summit held in February 2017, Paytm CEO Vijay Shekhar Sharma announced that Paytm was on the path to achieving annual transaction volume of nearly $10 billion in the year ending March 31, 2017. At the conference, Sharma also said that Paytm recorded 8.5 million transactions every day, while India’s daily debit and credit card transactions combined total only about 10 million. This indicates that Paytm commands a significant proportion of the market.