DIpil Das

Introduction

Over the past decade, grocery discounters Aldi and Lidl have taken the UK by storm, stealing market share from major incumbent rivals, and forcing those rivals to take radical measures to slash costs, lower prices and overhaul offerings. This report reviews five measures major UK grocery retailers have taken to fight Aldi and Lidl – and summary verdicts on the success of each. We begin with an outline of the past and potential future growth of Aldi and Lidl in the UK.Grocery Discounters: The UK Context

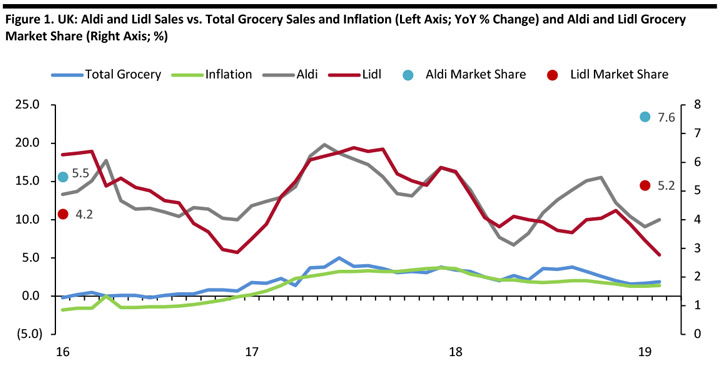

Discounters’ Gains In the UK, discounters Aldi and Lidl have reshaped the grocery landscape. Sustained double-digit revenue growth at Aldi and Lidl has eroded the aggregate share captured by the traditional “Big Four” grocery retailers—Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons. According to market-measurement service Kantar Worldpanel, for the 12 weeks ended March 24, 2019, Tesco had a grocery market share of 27.4%, Asda 15.4%, Sainsbury’s 15.3% and Morrisons 10.3%. This compared to 8.0% market share for Aldi and 5.6% for Lidl. The chart below shows growth at Aldi and Lidl over the past three years (through February 24, 2019), as recorded by Kantar Worldpanel. We also show period-start and period-end market shares for Aldi and Lidl. Between January 2011 (not included in the chart below) and February 2019, Aldi and Lidl more than doubled their combined UK grocery market share from 6.1% to 12.8%. During that period, Aldi overtook the Co-Operative to become the UK’s fifth-biggest grocery retailer and Lidl overtook Waitrose to capture seventh position. [caption id="attachment_84306" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Data are for overlapping 12-week periods and attributed to the years in which the periods end. Market share data are for the 12 weeks ended Jan. 3, 2016 and Feb. 24, 2019.

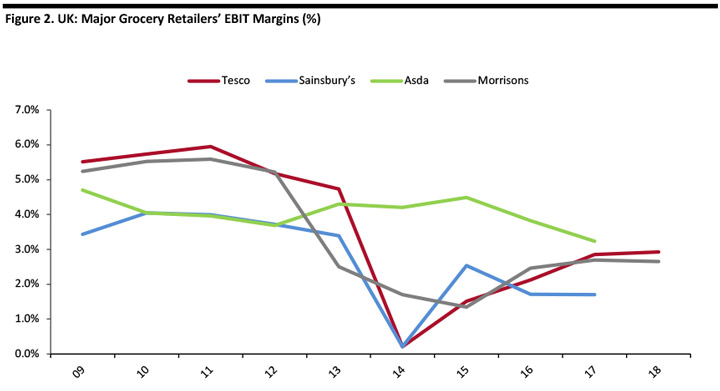

Data are for overlapping 12-week periods and attributed to the years in which the periods end. Market share data are for the 12 weeks ended Jan. 3, 2016 and Feb. 24, 2019. Source: Kantar Worldpanel [/caption] The impact on incumbents has been felt in attrition of margins as well as loss of market share. Established nondiscount retailers were forced to cut prices to compete, just as they saw weakening sales volumes as shoppers turned to low-price rivals. [caption id="attachment_84307" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

Source: S&P Capital IQ[/caption]

Tesco and Morrisons are among those focusing on volume-led recoveries — and this has generally borne fruit, according to recent management commentary:

Source: S&P Capital IQ[/caption]

Tesco and Morrisons are among those focusing on volume-led recoveries — and this has generally borne fruit, according to recent management commentary:

- On Tesco’s 3Q19 earnings call in January 2019, CEO Dave Lewis said the retailer “led the market from both a volume and a value perspective in food, general merchandising and clothing.”

- On Sainsbury’s 1H19 earnings call in November 2018 CFO Kevin O’Byrne said: “We've seen one of the most encouraging volume performances that we have for a number of years. Volumes are down slightly, but [represented a] material improvement year on year.” In 3Q19, management pointed to “a broadly similar volume performance” to 1H19.

- On Morrisons earnings call in for fiscal 2019 (ended January 2019), CFO Trevor Strain said: “the volume performance of the group is strong” and that volumes were “stable” in its core supermarkets (excluding online and wholesale).

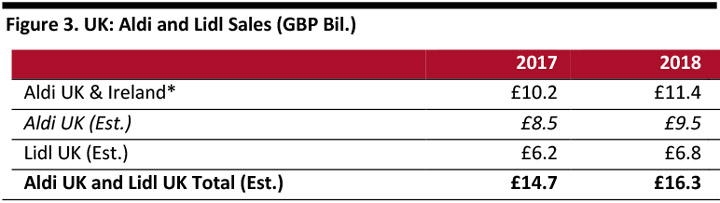

2017 actual; 2018 estimated based on average annual growth recorded by Kantar Worldpanel.

2017 actual; 2018 estimated based on average annual growth recorded by Kantar Worldpanel. Source: Company reports/Kantar Worldpanel/Coresight Research [/caption]

- Aldi UK and Ireland grew revenues by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.2% between 2012 and 2017 (latest confirmed). In 2017, it grew revenues by 16.4%. Kantar Worldpanel data imply it grew UK-only sales by around 12% in 2018, slowing from Kantar-implied UK-only growth of around 16% in 2017.

- Lidl UK grew revenues by a CAGR of 15.4% between 2013 and 2018, and by 13.0% in 2018, according to Euromonitor International estimates.

- Combined Aldi UK and Lidl UK estimated sales of just over £25 billion in 2023, up by an aggregate £9 billion from estimated 2018 sales.

- Aldi UK and Ireland sales of around £17.5 billion by 2023, up by around £6 billion in total from estimated 2018 revenues. Within this, we estimate Aldi UK (ex Ireland) would grow sales by around £5 billion to approximately £14.6 billion.

- Lidl UK sales of around £10.5 billion in 2023, up by almost £4 billion from estimated 2018 revenues.

- 20% of Tesco UK and Ireland fiscal 2018 revenue (note, including Ireland).

- 31.5% of Sainsbury’s fiscal 2018 retail revenues (ex financial services).

- 40% of Asda’s 2017 revenues (latest confirmed).

- 50% of Morrisons recently reported fiscal 2019 revenues.

Five Ways UK Grocery Retailers Have Fought Aldi and Lidl

We note five strategies that incumbent retailers have adopted to compete in this environment. 1. Cutting Out Costs to Lower Prices The Big Four have been forced to invest in price, and at retailers such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s, this has involved a general switch from special offers such as multibuys to more steady everyday lower pricing. At the same time, some retailers have been seeking to rebuild margins after a depletion in recent years. All Big Four have been cutting costs to achieve these aims. This has resulted in thousands of job cuts, in which the general pattern has been to move from head office to stores:- Tesco is aiming to reduce operating costs by £1.5 billion and grow operating margins to 3.5-4.0% by fiscal 2020. In 2015, Tesco closed its Cheshunt headquarters, shedding 2,000 jobs; reformed its staff pension scheme; and, shuttered stores – including a single tranche of 43 stores. In 2017, the company cut 1,200 jobs at its head office and announced plans to close a call center, shedding 1,100 jobs. In 2018, Tesco cut 1,700 jobs in stores and warehouses (while creating 900 other roles). It is currently planning to shut fresh-food counters in 90 stores with some other stores switching to a reduced counter service, cut store-based staff canteens and make further job cuts at its head office, in total impacting 9,000 staff.

- In 2017, Sainsbury’s cut 2,000 head-office roles and 400 jobs in stores. In 2018, the company cut an unspecified number (widely reported to be in the thousands) of store-level jobs when it axed the roles of deputy manager, department manager, team leader and store supervisor.

- In 2016, Asda cut around 200 head office jobs and around 1,000 store jobs as it closed staff canteens and some in-store services. In 2017, the retailer cut 300 head-office posts, sought to cut an unspecified number of posts at some underperforming stores, according to the Guardian newspaper, and revealed plans to remove the role of 842 section leaders from its store management teams. In October 2018, The Grocer reported Asda plans to cut 2,500 store posts.

- Morrisons cut 700 head-office staff in 2015 and 1,500 store-management roles in 2018 (while creating 1,700 more junior roles).

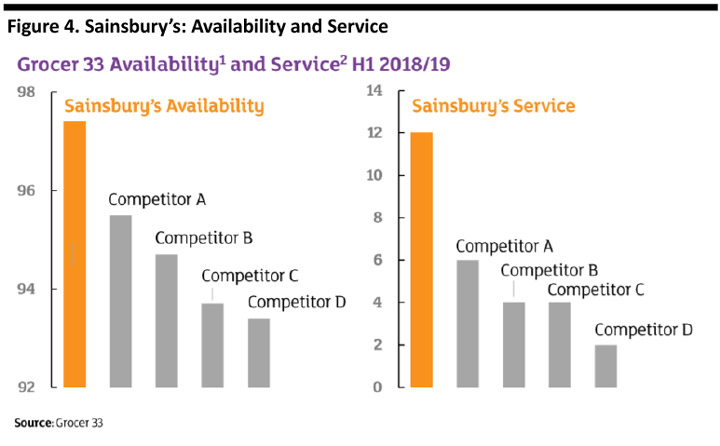

The Grocer 33 is a weekly mystery shopping survey undertaken across various supermarket chains by The Grocer magazine.

The Grocer 33 is a weekly mystery shopping survey undertaken across various supermarket chains by The Grocer magazine. 1Grocer 33 average availability (percent) for the 28 weeks ended Sept. 22, 2018

2Grocer 33 service wins for the 28 weeks ended Sept. 22, 2018

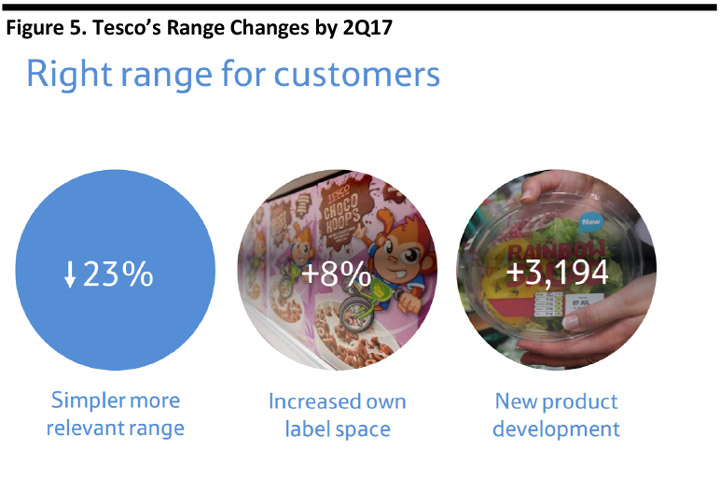

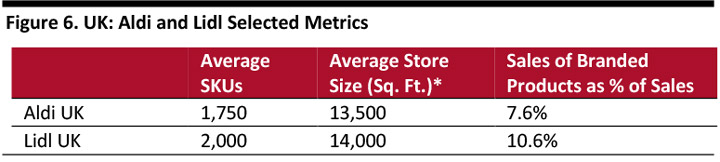

Source: Company reports [/caption] Nevertheless, the position of Sainsbury’s has always been firmly upscale of that of its biggest rivals, and we think that that position is slipping. Sainsbury’s continues to face a significant challenge in heading off the discounters on price (at least to some extent) while maintaining its differentiated position; it now seems willing to sacrifice that differentiation in a bid to cut costs. 2. Driving Volumes through Slimmed-Down Ranges A key part of Aldi and Lidl’s operating model is to offer limited choice — traditionally, a single private-label stock-keeping unit (SKU) in each category — and channel high volumes through each SKU. In most supermarkets, an abundance of choice dilutes sales per SKU. However, nondiscount retailers have been borrowing ideas from the discounters. Under CEO Dave Lewis, one plank of Tesco’s strategy has been to slim down its ranges. In 2015, Tesco was reported by the Guardian to be planning a cut of up to 30% of its total offering. At the end of fiscal 2016, Tesco noted it had cut its total number of products by 18% under its “Project Reset.” At the end of fiscal 2017, Tesco noted it had achieved a 24% cumulative range reduction while maintaining a strong pipeline of new product development. [caption id="attachment_84310" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Branded suppliers have seen delistings, though Tesco management has noted that some suppliers benefit from higher volumes going through their core ranges. However, simplifying and removing supplication from private-label ranges and removing duplication have contributed, too. In 2018, The Grocer magazine reported that Tesco is embarking on a cull of suppliers, which could involve cuts to its ranges. On the company’s 1Q19 earnings call, Dave Lewis remarked, “If we've got range which is not productive, that's taking up the space at the volume that we need for the highest-selling lines, then we'll continue to change the portfolio accordingly.”

At the same time, Tesco has been relaunching thousands of private-label products: In its 3Q19 trading update, Tesco said 74% of 10,000 private-label products had so far been relaunched. And it gave those own-brands greater prominence on shelf, encouraging more favorable private-label-versus-private-label comparisons between Tesco and the discounters.

VERDICT: A successful move to drive volumes per SKU

Tesco’s range reductions have allowed it, on average, to more profitably channel higher volumes through each line. Its range resets have coincided with a recovery in its top line and a return to total volume growth, confirming that shoppers have not been deterred by slimmed-down ranges. The retailer’s product range remains more substantial than those of the discounters, giving it a strong competitive advantage.

3. Launching Their Own Discount Formats and Brands

Tesco has been imitating the discounters not only in reducing choice but in building its own discounter-type brands. In January 2019, the company reported that its new low-price “Exclusively at Tesco” brands had been 95% rolled out and that 82% of Tesco shoppers had bought items from the range. On the company’s 3Q19 earnings call, CEO Dave Lewis acknowledged demand for these low-price products, which replaced its previous Everyday Value range, had brought some trading down from more expensive (and so higher-margin) ranges but said that he was “very comfortable with the level of adoption” and its impact on the business.

[caption id="attachment_84311" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

Source: Company reports[/caption]

Branded suppliers have seen delistings, though Tesco management has noted that some suppliers benefit from higher volumes going through their core ranges. However, simplifying and removing supplication from private-label ranges and removing duplication have contributed, too. In 2018, The Grocer magazine reported that Tesco is embarking on a cull of suppliers, which could involve cuts to its ranges. On the company’s 1Q19 earnings call, Dave Lewis remarked, “If we've got range which is not productive, that's taking up the space at the volume that we need for the highest-selling lines, then we'll continue to change the portfolio accordingly.”

At the same time, Tesco has been relaunching thousands of private-label products: In its 3Q19 trading update, Tesco said 74% of 10,000 private-label products had so far been relaunched. And it gave those own-brands greater prominence on shelf, encouraging more favorable private-label-versus-private-label comparisons between Tesco and the discounters.

VERDICT: A successful move to drive volumes per SKU

Tesco’s range reductions have allowed it, on average, to more profitably channel higher volumes through each line. Its range resets have coincided with a recovery in its top line and a return to total volume growth, confirming that shoppers have not been deterred by slimmed-down ranges. The retailer’s product range remains more substantial than those of the discounters, giving it a strong competitive advantage.

3. Launching Their Own Discount Formats and Brands

Tesco has been imitating the discounters not only in reducing choice but in building its own discounter-type brands. In January 2019, the company reported that its new low-price “Exclusively at Tesco” brands had been 95% rolled out and that 82% of Tesco shoppers had bought items from the range. On the company’s 3Q19 earnings call, CEO Dave Lewis acknowledged demand for these low-price products, which replaced its previous Everyday Value range, had brought some trading down from more expensive (and so higher-margin) ranges but said that he was “very comfortable with the level of adoption” and its impact on the business.

[caption id="attachment_84311" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Exclusively at Tesco brands

Exclusively at Tesco brands Source: Tesco [/caption] Tesco has launched discount-format stores, too. In autumn 2018, the company launched Jack’s, which, like Aldi and Lidl, is built on a proposition of small stores, limited ranges and a private-label focus. [caption id="attachment_84312" align="aligncenter" width="731"]

Jack’s store

Jack’s store Source: Tesco [/caption] However, we note some differences to the offerings at Aldi and Lidl, which we think put Jack’s at a potential disadvantage:

- Instead of stocking the kind of “fake brands” that customers see in Aldi and Lidl, all of its private-label products are offered under the Jack’s name. Aldi’s and Lidl’s brands encourage shoppers to switch from a brand-heavy basket of goods at nondiscount retailers to a private-label-focused basket at discounters. The single-label strategy at Jack’s could prevent such switching. Moreover, if shoppers are happy to fill their carts with a single value private label, they can do that at a nondiscount retailer — such as Tesco.

- Aldi and Lidl have developed very strong premium lines, including the Specially Selected brand at Aldi and the Deluxe brand at Lidl. Jack’s offers a single tier of products, providing little opportunity for shoppers to trade up.

- Our final concern regards the Jack’s claim that “8 out of 10 food and drink products will be grown, reared or made in Britain.” In the UK, Aldi and Lidl have strongly pushed their British sourcing credentials — but this push has largely been limited to fresh categories such as meat, dairy, fruit and vegetables, while imported products have made a significant contribution to the two grocers’ premium ranges. The Jack’s 80% British promise makes it difficult for the banner to cater to this demand for imports, and this challenge dovetails with the limited premium offering mentioned above.

- Disposing of a large tranche of stores, or even one of the Sainsbury’s or Asda banners, could undermine the economics of the merger.

- The merged company may struggle to dispose of the large number of superstore sites it has: Rivals may not be interested in superstores given that UK grocery retailers are shifting from large stores to smaller formats — and are opening fewer stores.

Key Insights

- Nondiscount grocery retailers have undertaken radical cost-cutting, shedding thousands of staff in several rounds of job cuts at head-office and store levels. Generally, the visible impact to shoppers seems to have been minimal. However, we perceive a slippage in store standards at Sainsbury’s that is risking its long-established differentiation.

- Range reductions have allowed Tesco to channel higher volumes through each line. Its range resets have coincided with a recovery in its top line and a return to total volume growth, confirming that shoppers have not been deterred by slimmed-down ranges.

- Tesco’s new, discounter-type private labels look to be a success, although they are encouraging some trading down at the retailer. Tesco’s launch of the Jack’s chain is a bold move, but we think the position at the lower end of the discount spectrum limits its appeal.

- Diversification away from core grocery retailing has been successful, creating new revenue streams and growing grocery volumes through nontraditional channels and giving retailers access to higher-margin or faster-growing markets. The wholesale model, such as that adopted by Morrisons, looks particularly successful: Wholesale has driven its strong comparable sales growth.

- There are doubts over whether the planned Sainsbury’s-Asda merger will succeed. Sainsbury-Asda and current market leader Tesco would in total control almost 60% of the UK grocery market, creating an exceptionally consolidated market. And the CMA’s announcement indicates it would require a substantial number of store disposals or even eliminating either the Sainsbury’s or Asda brand, which would undermine the economics of the merger.

*Based on new stores.

*Based on new stores. Source: Company reports/Kantar Worldpanel/CMA/Coresight Research [/caption]